The Dark Side of Beauty

In the 1,000-line poem Endymion, John Keats contemplates beauty as the engine of human existence. “A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” its opening line declares. Beauty exists for no reason other than affirmation of our aliveness, a sentiment best embodied by art and personal valuables. Society venerates beauty and people go to extreme lengths to attain it. However, the pursuit of beauty occasionally takes darker forms, such as art theft.

Art theft should not be solely romanticised as quest for beauty. Instead, it often stems from greed and exploitation. Nowhere is this more apparent than in wartime contexts, such as the Holocaust. “Aryanization,” the systematic forced property transfer of Jews to non-Jews, facilitated the theft of over 650,000 artworks and valuables from Jewish families. These looted treasures are physical embodiments of hope, heritage, and remembrance. While society rightfully perceives Nazi plunder as a reprehensible act, this interpretation does not always extend to other instances of cultural theft. At the end of the day, it’s human actions that powerfully shape our judgements, not the art.

Monuments Men Carrying Nazi-Looted Art. Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany, 1945. Photo Courtesy: The Huntington.

The flip side of pursuing beauty is safeguarding it. Jews took extraordinary measures to preserve their belongings, even at the risk of death. In 2016, Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum staff found a hidden secret among thousands of kitchenware pieces. A gold ring and necklace were wrapped in canvas and concealed in a mug. [1] Not only does this reflect desperation, but also a glimmer of hope for its preservation. Tragically, the greed of Nazi officials eclipsed any concern for preserving beauty.

Gold Ring Preserved in Canvas. Photo Courtesy: BBC.

250 miles away from Auschwitz, Nazi commandant Franz Stangl describes his arrival to Treblinka. “I stepped knee-deep into money... I waded in notes, currency, precious stones, jewellery, clothes… there was more money and stuff around than one could dream of, all there for the taking.” [2] Stangl accounts for the mindset of Nazi officials: mesmerised not by the immortal beauty of Jewish “stuff,” but by their repugnant personal agenda. They also commonly distributed looted goods to local communities to garner popular support. [3]

Locals wanted in on the wealth, too. As Treblinka closed in October 1943, people dug through graves at the site to recover valuables overlooked by the Nazis. The scene was described with terms such as "Eldorado," "Klondike," and "gold rush." [4] Like the Nazis, the community had no interest in preserving what they stole. Instead, they sold things off to acquire cash or foreign currency -- a clever way to store capital during state socialism. [5]

The contrast between the callousness of Nazis and individual art thieves like Stéphane Breitwieser could not be more apparent. In the 90s, the Frenchman managed to steal a collection worth over $2 billion dollars. He avoided arrest for years by never attempting to profit a cent. Instead, motivated solely by the beauty of art, he operated without resorting to violence or the threat thereof. This earned him recognition as "one of those rare exceptions," by journalist Michael Finkel. [6] People were less repulsed and more intrigued by Brietwieser’s peaceful style of theft, and judged him on a different moral scale.

Brietwieser judged himself on this scale, too. He was appalled that the French media referred to his crimes as “the biggest pillage of art since the Nazis.” [7] In his eyes, he was a pathologically obsessed art collector, not a pathological criminal. And the justice system seemed to agree: he only served two years in prison, even though many of the priceless works were destroyed by Brietwieser’s mother.

Breitwieser isn’t unique in his minimalist punishment. The law also struggles with Nazi-era art theft. For decades, the international art community blissfully ignored Nazi-looted art. In fact, the first real discussion of restitution didn’t even occur until 1998, when representatives from 44 counties and 13 NGOs converged to establish the Washington Principles. The eleven nonbinding guidelines began to change the attitude about Nazi-stolen goods, encouraging transparency in dealing with confiscated art. In other words, they pleaded governments to have a shred of decency.

Unfortunately, the Washington Principles did not do much. Twenty-five years have come and gone, and over 100,000 stolen valuables remain unaccounted for. [8] Prompted by this lack of progress, on March 5th, 2024, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken released the Best Practices for the Washington Principles. In addition to building upon the original guidelines, they recognize "art” as encompassing all cultural property, including items belonging to individuals, communities, and organizations. [9]

Proceedings from Washington Conference. Photo Courtesy: Center for Art Law.

Centuries-old wartime plunder follows a similar quest for reclamation. In 1648, the Swedish army swiftly captured the Prague Castle and its fabled treasures. These riches, amassed by the late Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, included an eclectic array of art, rare books, astronomical instruments, and other curiosities from around the world. Among these treasures is the Silver Bible, cherished by the Czechs as one of the only surviving examples of the Gothic language. Today, the Silver Bible is still in Swedish hands despite many efforts to get it back. Historian Colin Woodward discusses difficulty in determining who owns ancient artifacts, such as the Silver Bible: “the Ostrogoths who created it died out centuries ago, and the Czechs weren’t in control of Prague when the Swedes arrived in 1648… at this point, the Swedes have possessed the book six times longer than anyone in Prague ever did, so it is not surprising that they don’t feel compelled to hand it over.” [10]

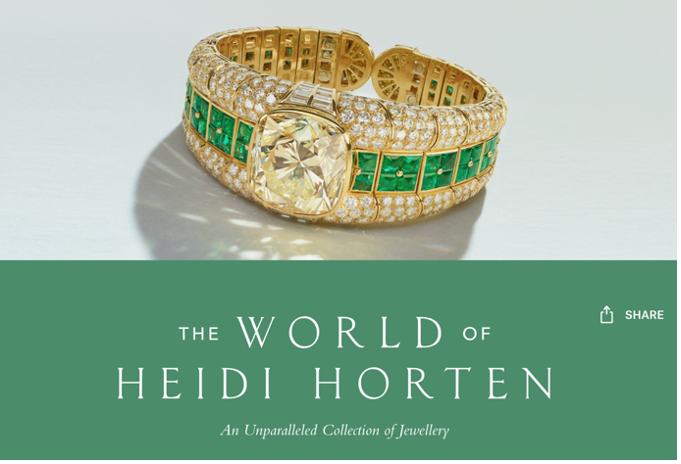

Financial interests also sway opinions over rightful ownership. In 2023, Christie’s auctioned over $200 million worth of jewelry, featuring the remarkable 90-carat diamond “Briolette of India,” and a $20 million Cartier diamond ring. Truly incredible pieces that are tarnished by their linkage to Nazi-theft. Heidi Horten’s estate, the late wife of Helmut Horten, owns the jewellery. Helmut Horten was a prominent Nazi who amassed his fortune by exploiting aryanization laws, which allowed his widow to acquire a jewelry collection valued at $150 million.

Heidi Horten Auction Page. Photo Courtesy: Christie’s

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) denounced the auction and claimed that “both Christie’s and Heidi Horten’s foundation stand to benefit from this sale.” [11] They called for an immediate halt to the sales and a serious restitution effort.

This did not happen. Instead, Christie’s added that “the business practices of Mr. Horten during the Nazi era, when he purchased Jewish businesses sold under duress, are well documented,” and promised to “make a significant contribution from its final proceeds…to organisations that further advance Holocaust research and education.” [12] The thing is, all of the jewellery in question was acquired in the 1970s via auctions rather than overt theft. From Christie’s perspective, if the objects weren’t stolen outright, the auction was fair game. The assumption is that collectors are adults who can decide how to spend their money. [13]

Nevertheless, this incident prompted Christie's to encourage expanding its scrutiny of the history of auctioned works. They stressed that the art market is obliged, “not only to research and document the ownership history of the works themselves, but also to examine the very source of the wealth used to purchase them even if they were bought in recent years, if that wealth was built during the Nazi-era.” [14] The Horten case exposes the importance of the actors involved for art theft.

Restitution often hinges on the item’s provenance, as exemplified by Gustave Courbet's painting, "La Ronde Enfantine.” Unlike Horten’s jewelry, the painting was successfully restituted to the heirs of Robert Bing. The painting has a complex history: seized from the Parisian flat of Robert Léo Michel Lévy Bing in 1941 by two members of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the Nazi organization dedicated to cultural property theft. After being seized, it was held in the Jeu de Paume in Paris for the benefit of the prominent Nazi collector Hermann Göring. The artwork was also part of a transaction involving Ribbentrop, but this exchange failed due to Ribbentrop’s or his wife’s distaste for the piece.

Gustave Courbet, “La Ronde Enfantine” (around 1863). Photo courtesy: The Art Newspaper.

The panel's recommendation stressed that no criticism is directed at the museum or the original donor, Reverend Eric Milner-White. Both entities acted honorably and in accordance with the standards prevailing at the time of acquisition and since. [15] Honorable behavior doesn’t change how the art came into possession, but it certainly influences our perception of the incident.

Deliberate seizures of cultural property, especially when involving violence, evoke great sympathy toward victims. It’s easier to justify restitution efforts for pieces stolen for financial gain rather than for their intrinsic beauty. This is because society recognizes that some belongings hold immeasurable value beyond monetary worth. Michael Finkel argues, “if your house was burning, you’d take your photo album and your kids’ drawings—those are worth nothing, but they’re worth everything.” [16]

Art theft is fueled by a spectrum of motivations: overt stealing motivated by greed, theft driven by a fascination with beauty, and even instances where the thief may not realize they're committing a crime. As aptly expressed by U.S. Ambassador Colette Avital, items stolen or later acquired by Nazis are not merely masterpieces. Regardless of how they were stolen, “they are the silent witnesses of the lives and loves of individuals, families and communities who were murdered cruelly and whose memories we cherish.” [17] Art is a witness to life and love, belonging to those who will honor those legacies. Ideally, restitution would rest alone on this idea. However, our judgements of art theft tends to be influenced more by the manner it occurs in than the item itself.

Footnotes:

“Auschwitz Mug Reveals Jewellery Hidden 70 Years Ago.” The Guardian, May 19, 2016.

Volha Charnysh and Evgeny Finkel, “The Death Camp Eldorado: Political and Economic Effects of Mass Violence,” Cambridge University Press, August 10, 2017.

Lorraine Boissoneault, “A 1938 Nazi Law Forced Jews to Register Their Wealth—Making It Easier to Steal,” Smithsonian.com, April 26, 2018.

Volha Charnysh and Evgeny Finkel, “The Death Camp Eldorado.”

Volha Charnysh and Evgeny Finkel, “The Death Camp Eldorado.”

Geoffrey Gagnon, “How Did One Man Steal $2 Billion in Art?” GQ, June 27, 2023.

Geoffrey Gagnon, “How Did One Man Steal $2 Billion in Art?”

Michael Ruane, “Many Countries Lag in Returning Art Looted by Nazis, Report Finds,” The Washington Post, March 6, 2024.

“Best Practices for the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art,” U.S. Department of State, March 5, 2024.

Colin Woodward, “The War over Plunder: Who Owns Art Stolen in War?,” HistoryNet, April 13, 2016.

“AJC Statement on Christie’s Auction of Nazi Aryanized Collection ‘World of Heidi Horten: Magnificent Jewels,’” AJC, May 8, 2023.

“The World of Heidi Horten,” Christie’s, May 3, 2023.

Katya Kazakina, “The $202 Million Sale of Heidi Horten’s Jewels Was a Massive Success. Its Aftermath Continues to Haunt Christie’s,” Artnet, July 10, 2023.

Katya Kazakina, “The $202 Million Sale of Heidi Horten’s Jewels Was a Massive Success.”

Gareth Harris, “Courbet Painting-Seized by the Nazis and Owned by a Reverend-to Be Returned to Its Original Owners,” The Art Newspaper, March 30, 2023.

Adrienne Westenfeld, “How One Man Stole $2 Billion Worth of Art,” Esquire, June 27, 2023.

Carlie Porterfield, “Most Countries Have Made Little to No Progress in Returning Nazi-Looted Art, Report Finds,” The Art Newspaper, March 6, 2024.

Lily Holmes

Luxury Editor, MADE IN BED