Mary Longe

Melancholy Chronicles, or Happy Continuum

Interacting with art, we often search for answers. We try to figure out what we see, feel, or even know by simply looking at a work of art. Contemporary artists give us ample opportunities to practice this approach. The best part, and often the most rewarding, is to later hear from the artist and determine how close you’ve come to getting it right.

Looking at Mary Longe's collages and stencil works, you find it hard to shed a sense of unease. Put together, they form a procession which emits a persistent, albeit subtle, signal of distress. In some of her works, geometrical shapes and grid-like patterns evoke entrapment; in others, her chosen compositions ponder the idea of isolation. In many of Longe’s pieces, her semi-abstract figurative elements seem to question our very reality.

Mary Longe.

To learn more about Mary’s practice, please visit her website or Instagram.

I met Mary Longe at The Sotheby’s Institute of Art, where we were both enrolled in the Art and Business semester course. I remember, during our introduction session, she said that Impressionists were like a gateway drug to art. Indeed, Impressionists are rather easy to fall in love with. And Mary, too, got hooked. As I was getting to know Mary in our student milieu, I realised I had met someone unstoppable. At 71, an emerging artist, she was (and still is) more than ever ready to explore and push her own boundaries both in life and in art.

‘Middle age is anytime before death’, says Longe. For decades she was in leadership, executive, and other important roles in healthcare consulting services. She enjoyed a fulfilling career. But Longe has been a creative type all her life too.

She calls herself a maker. As she grew up, holiday gifts and family presents ‘were to be made, not bought’ – a rule that placed creativity into a category of traits sine qua non. There were also childhood visits to The Detroit Institute of Arts, which boasts one of the largest and most significant art collections in the United States. From ancient and indigenous art, to European masters and modernism, those childhood encounters inspired Longe’s initial curiosity. Her aesthetics were shaped by exposure to the artistic expression found across all eras and continents.

Bankrupt. Collage, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

Chicago, where she now resides, is known not only as the Windy City but also as the Artists’ City. Home to over sixty art museums and countless galleries – with its unique architecture, sprawling parks, and surrounding lakes and preserves – the area offers no shortage of visual inspiration. Art lovers often stand no chance but to succumb to expressing themselves in some type of artistic pursuit. And Longe was compelled to do just that. The final impetus happened not in Chicago but in Taos, New Mexico, where she spent a holiday ten years ago. One very early morning exploring the area, she came upon an inspirational sighting – artists with easels painting a mountain scene en plein air. She had a revelation: it was exactly what she wanted to do. Returning home she picked up a brush and never looked back.

Her artistic immersion began with weekend classes and workshops. She recalls with a special fondness the classes led by a prominent architectural water-colourist, Thomas Schaller. The 18-month course at the Palette and Chisel Academy of Fine Art in Chicago finally took her efforts to the next level. This is where she learned and systematised the indispensable foundations: mark-making, values, perspective, colour theory, pigments, etc. ‘By the end of it, I felt competent and confident’, says Longe.

When asked about her favourite names in Art History, Longe unsurprisingly reveals an eclectic range of creatives. She feels equally deferential to the genius of Michelangelo or Diego Velázquez, as she is infatuated by such art rebels as Kasimir Malevich and Takashi Murakami.

Her own practice started rather traditionally, with her work mostly being inspired by Impressionists and classic landscape painters. She joined an open-air group of Chicago artists and found herself regularly venturing out to the great outdoors painting natural scenery and enjoying the process. Eventually, however, and perhaps inevitably, Longe became drawn towards more abstract imagery.

We know of a great number of artists who experienced the shift towards abstraction many years, or even decades, into their careers. Longe seems to have developed a more liberated, expressive methodology in just five to seven years of her dedicated artistic venture. Of course, unlike her rule-breaking predecessors, such as Pablo Picasso, Frida Khalo or Joan Mitchell – also cited amongst her favourites – she had modern art to inform her progress. Simply put, Longe did not need to invent a new approach or technique and had the luxury to experiment with those already introduced by these great artistic figures. But she did have to find what resonated with her aesthetics, and then she had to make it her own.

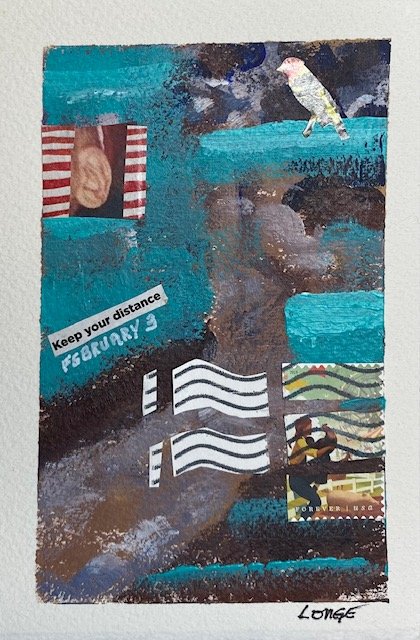

Postmarked. Collage of original painting and mixed media, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

‘Necessity is the mother of invention’, says Longe. The pandemic forced many an artist to create outside of their habitual routines. Or, as it was in Longe’s case - inside. Not that she could not leave her house, but group outings she was previously part of were no longer an option. Chicago winters, too, were not exactly conducive to painting out in the open. So she had to construct a new way of seeing and thinking.

She has played with collages throughout her life, but perhaps because the pandemic locked her up inside her own four walls, she began taking the technique seriously. ‘Early on it was using words and images from magazines to create a new image’, shares Longe. Later she began adding acrylic and watercolour to the mix, then stencil printing and photography. In effect, she diversified and devised her own principles of assemblages.

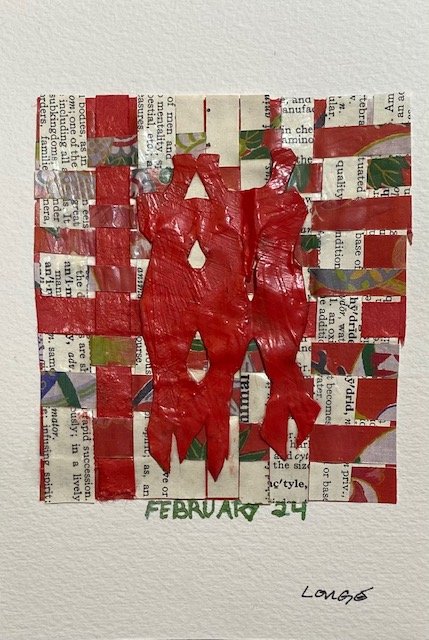

Togethering. Collage with woven paper and mixed media, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

Longe produced this aforementioned series of deconstructed works during lockdown. And now, looking at it, one relives the anxiety of that difficult period. But these works are much more nuanced than that. The sense of melancholy embedded in her works is contrasted with vibrant colours. It is as if they offer certainty of better days to come. Faith lives in her works as an ‘intellectual knowledge.’

Longe’s rule was one composition a day. And each day brought on a new feeling or a different query. Those changing moods found their release and expression through Longe’s imagery. One can peruse her collage and stencil works as if leafing through a personal diary. Each piece is a short abbreviated statement. Made in a small format, usually the size of a postcard or a notebook page, they file before us as a parade of life vignettes. There is something akin to a meditative practice. They evoke a sense of longing, of hope mixed with sadness, and likewise of joy and gratitude; all these feelings embedded in each work – intentionally or not – now speak to us about the resilience of humanity itself.

Longe’s art is not meant to be verbalised, yet lends itself so welcomingly to interpretations. Incorporating text within her collages makes interacting with them that much more interesting. In some cases the snippets of printed text cut out from printed pages help in decoding the message. She may include lines from poems or throw in a short sentence, as in the image below. Other times, Longe uses text strictly for its graphic properties, as if creating a metronome-like black-and-white background to contrast with the colourful and spontaneous foreground elements.

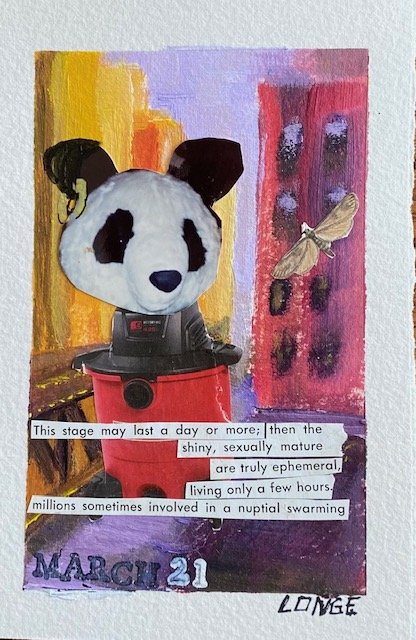

A Day in the Life. Collage with original painting and mixed media, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

Although Longe’s visual diaries are small in format, they pack quite a punch. In work pictured below, her striking colour combinations, tilted compositions, and jagged lines result in images that drive us to the point of apprehension.

It is easy to get lost in all the small details and layers. In some works, we find shapes bearing semblance to dancing bodies, with hands exultantly thrown up in the air, birds as symbols of the purest sense of freedom, or flowers which though withering, still delight with their beautiful colours.

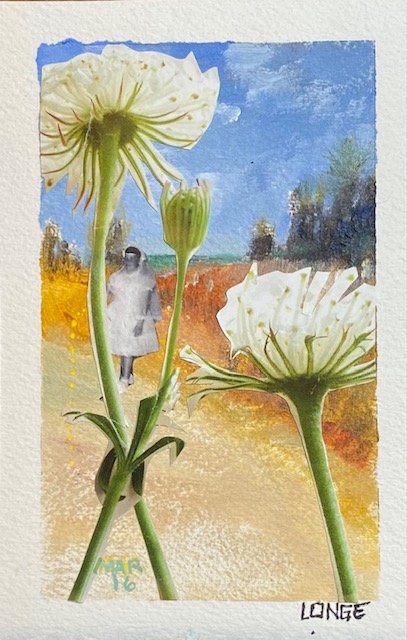

City Life. Collage with original painting and mixed media, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

In contrast to the exuberant stencil image above, the collage with an old photo of a bride offers a very different tone. Ruminating on a subject of a newly formed love union, Longe neglects to place a groom in the composition. The move is deliberate, and we are left to decipher the meaning of this omission.

A serene landscape, a setting in which Longe traffics comfortably and confidently, offers the soothing natural palette as a backdrop to a human drama about to unravel. It would be too simplistic to infer that the old photo references the artist’s personal history. More broadly, it appears that Longe examines lonesomeness as part of our existence. Here again, we detect that sense of longing which seems ubiquitous in her works. The tension is further heightened by the imposing presence of the colossal white flowers. They look like they might belong to the carnivorous plant species: their beauty attracts, then devours.

Shoreline. Collage with original painting and mixed media, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

Nature provides the biggest source of inspiration to Longe. If there is an overarching thesis to her works, it is this: for as long as humans nurture their bond with it – even in the most densely populated city, even during lockdown, and even inside one’s house – mankind may be healed.

Longe produced approximately 100 compositions in 2020. These works, if put together in one enormous canvas, reveal not only how she honed her artistic faculties but also how she visually expressed her unstoppable spirit and innovative outlook. To observe and decipher where the artist’s head was at every stage of that creative period is fascinating. Perhaps the entire collection will find its way into a beautifully published book one day. Or into a solo exhibition. Until that day comes, Longe remains the busiest creative I know.

Swoop. Collage with mixed media, 10.16 cm x 15.24 cm.

Half-jokingly, but only half, Longe swears by the 10,000-hour rule. There is no doubt her relentless daily production of collages and stencil prints has made her a more confident artist and poised her to step outside her comfort zone once again. Currently, Longe is working on larger-scale pieces and is discussing a solo project with one of the galleries.

Apart from her artistic endeavours, Sotheby’s Institute of Art catapulted her on another exciting trajectory: she speaks to art enthusiasts, interviews collectors, and shares her art and soul with people around her. And – always – continues to create and learn.

All images are courtesy of the artist.

Irina Rothenberg

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED