The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism @ The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism is currently exhibiting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A masterclass in pre-World War II modern African American art, the exhibit comprises over 160 interdisciplinary artworks that depict modern Black life. The mediums in this exhibit ranges paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, literature, and video that covers the 1920 through 1940 timeframe, all laid out along nine spacious galleries, divided into thirteen sub-sections, with each work reflecting the philosophies of the movement’s Thinkers: Alain Locke, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Laura Wheeler Waring.

Aaron Douglas, Aspects of Negro Life – From Slavery to Reconstruction, 1934. Photo Courtesy: The New York Public Library.

A historical artwork that best explains the foundation for this artistic movement is Aaron Douglas’s 1934 seven-foot-tall mural, Aspects of Negro Life – From Slavery to Reconstruction. Located in the Cultural History gallery, this visual composition is to be viewed from right-to-left, with sections Douglas himself explained as “…the first section depicts the slaves’ doubt and uncertainty, transformed into exultation at the reading of the Emancipation; in the second section, the figure standing on the box symbolizes the careers of outstanding Negro leaders during this time; the third section shows the departure of the Union soldiers from the South, and the onslaught of the Klan that followed.” [1]

Left: Aaron Douglass, Let My People Go, 1935-1939. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Right: Augusta Savage, Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), 1939. Photo Courtesy: Lisa Black-Cohen, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The abolition of slavery in 1865, which was followed by the 1865-1901 Reconstruction period (when freed slaves were integrated into mainstream society), prompted segregationist laws and the 1868 birth of the white supremacist group, the Ku Klux Klan. The terror unleashed by the Klan, through lynchings and mob violence, along with no clear path to economic freedom nor access to education, were some reasons why millions of African Americans migrated from southern states to freer and safer northern states. This Great Migration laid the foundation for what was originally called The New Negro Movement, now referred to as The Harlem Renaissance.

Alain Locke, The New Negro Book, 1925. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This Harlem Renaissance marked the birth of an artistic and cultural celebratory shift within the New Negro cities of New York, Chicago, and St. Louis. This exhibit honors early 20th century African American modern art, when the modern Black subject was presented by modern Black artists through the interdisciplinary fields of art, music, literature, and dance.

William H. Johnson, Woman in Blue, 1943. Oil on Burlap. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For instance, in the Portraiture and the Modern Black Subject gallery, there are nineteen portraits that depict people from the working-class, elite, and professional areas of society. Portraits were created by artists such as Elizabeth Catlett, Laura Wheeling Waring, Archibald J. Motley and William H. Johnson. However, it is William H. Johnson’s 1943 oil on burlap portrait of the Woman in Blue, that is most recognisable, as this specific artwork was selected to promote this entire exhibit. This portrait depicts a forlorn African American woman wearing a Royal blue dress, seated on a yellow chair, with disproportionately large hands. As was described by the exhibit’s curator, Dr. Denise M. Murrell, she sees this portrait as “pulling in ideas of German Expressionism, Fauvism, African mask aesthetics…to depict the modern African American subject.” [2]

Palmer Hayden, The Janitor Who Paints, 1940. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Another thought-provoking painting in this gallery is Palmer Hayden’s 1937, The Janitor Who Paints. Set in a small, cluttered room, the painting is divided into a darker depressing right-side where the painter’s character exists, versus a colourful and hopeful left-side of the painting where a smiling well-dressed mother with a baby are seated. Like Johnson’s Woman in Blue, Hayden’s painter is also forlorn as both borrow from the German Expressionism technique which “emphasises the artist’s inner feelings…simplified shapes, bright colours and gestural brushstrokes.” [3] However, the two paintings differ since the latter is a protest painting and a metaphor for the two distinct artistic worlds, one of which African American artists were excluded from.

Archibald J. Motley, Blues, 1929. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the two galleries, The New Negro Artist Abroad: Motley in Paris and European Modernism and The International African Diaspora the movement’s transatlantic presence is evident. Archibald J. Motley’s 1929 painting, “Blues”, is a colourful scene in a crowded Parisian nightclub the artist frequented. A less common scene in America, Motley noted bi-racial couples dancing closely and freely while capturing the confidence and freedoms of women who flouted social norms by smoking cigarettes, dismissed ideas of modesty by wearing sleeveless blouses and above-the-knee dresses, and opted to wear their hair short. The patrons in these spaces were artists from Afro-Caribbean French island colonies, Africans from French colonies on the African Continent, Europeans, and fellow African Americans. The African American philosopher and promoter of this artistic movement, Alain Locke, encouraged these cross-cultural and cross-continental exchanges in his seminal work, ‘The New Negro’.

Henri Matisse, Aicha and Laurette, 1917. Photo Courtesy: Lisa Black-Cohen, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To continue to demonstrate the growing importance of the black figure in European art, this gallery showcases portraits by critically acclaimed European artist like Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch, Man Ray, and Pablo Picasso who chose Black subjects as central figures in their portraits. For instance, Matisse’s 1917, “Aicha and Lorette” is a dual portrait of a Black woman and a white woman seated next to each other. Black women were usually only present in paintings as either a servant or caregiver; by contrast, this sophisticated Black woman wears a well-tailored yellow -gold dress, her hair pinned-up in loose bun, while her white counterpart wore an emerald-green dress, black jacket but with loose long black hair. The artist’s choice to have the women side by side, and at the center of the painting, indicate an absence of any social or economic hierarchy between the two – a presentation, never before depicted in art. This reframing of the Black woman as an equal indicates a shift in ideas surrounding the value of blackness, and the importance of the Black subject in the modern European artistic world.

Laura Wheeler Waring, Marian Anderson, 1944. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the small Luminaries gallery, hangs only nine artworks that depict African Americans during the post-World War I and pre-World War II periods of 1918 through 1939. A few noteworthy artistic depictions of African Americans who found fame and respect in Europe include a bronze sculpture of baritone concert artists and actor Paul Robeson; a carbon print of dancer, singer, and artist Josephine Baker; a pastel portrait of sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois, and a silent two-minute black-and-white video of a dance performance by Josephine Baker and Katherine Dunham. The most memorable of this section is a 1944 Laura Wheeler Waring’s seven-foot-tall painting of opera contralto, Marian Anderson, in an elegant long-sleeved full-length red gown.

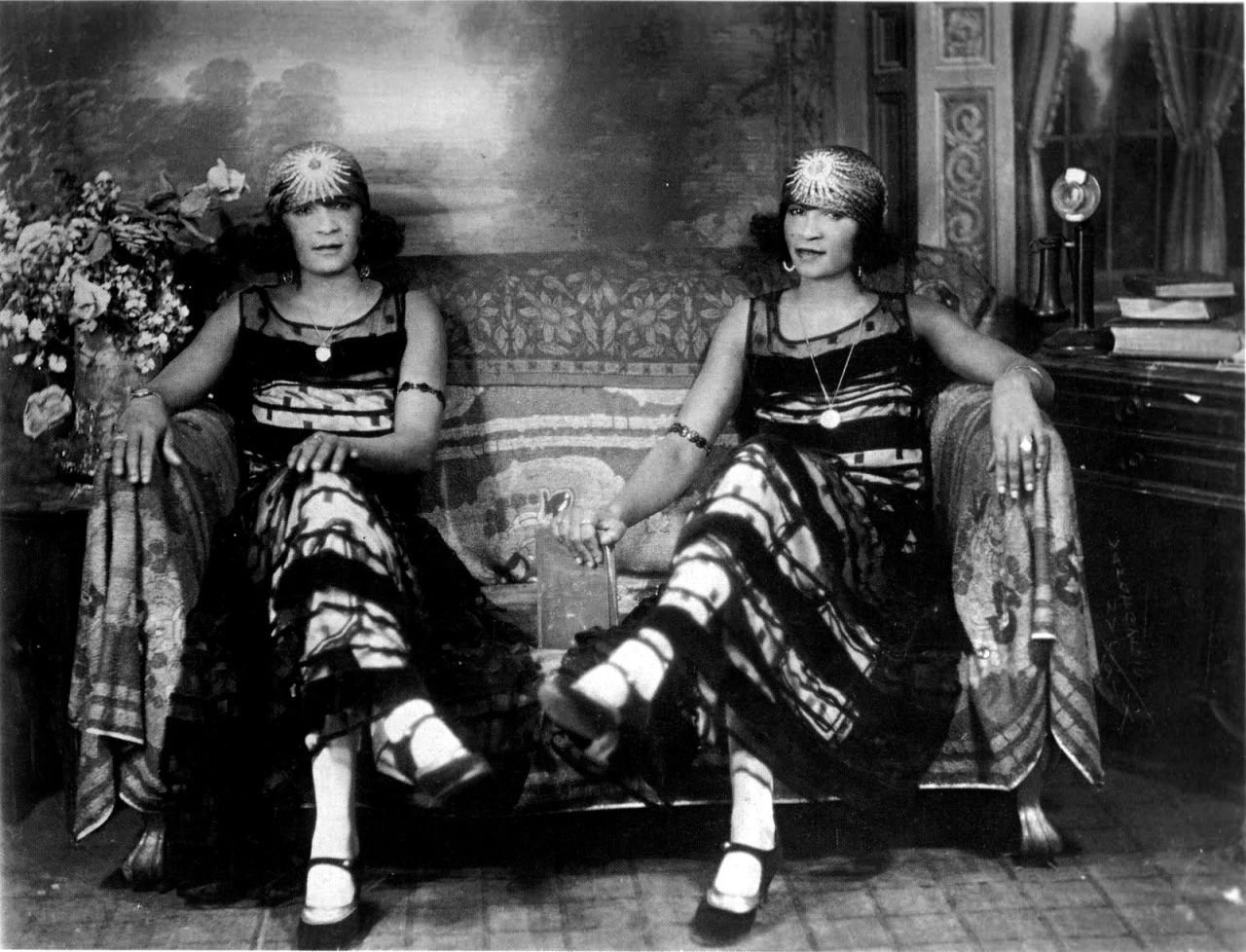

James Van Der Zee, Identical Twins, 1924. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Carl Van Vechten, Bessie Smith Holding Feathers, 1936. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In contrast with the ante room in the Luminaries section, the significantly larger Nightlife gallery offers ample seating for the many museum goers to view the silent three-minute video, “Jazz Music, and Dance Performances1929 through 1934”. The video’s three distinct sections include a 1934 excerpt of Cab Calloway’s Hi-De-Ho, a Lindy Hop dance performance, and Duke Ellington and his Orchestra at the Cotton Club. As the genre of Jazz was accepted as the soundtrack for this artistic movement, it is a silent character throughout each of the artworks in this gallery. From James Van Der Zee’s 1924 black-and-white photograph of the Flapper dress wearing Identical Twins, to the energy in Archibald J. Motley’s colorful 1934 painting, Black Belt, of an urban Chicago street scene, or in Carl Van Vechten’s 1936 Bessie Smith Holding Feathers; jazz, entertainment and nightlife are clearly intertwined.

James Can Der Zee, Marcus Garvey in a UNIA Parade, 1924. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lastly, in the Artist As Activist gallery, protest art is presented through sculpture, photographs, and paintings. Referencing race and the legal system, Aaron Douglas’s 1935 pastel on paper, Scottsboro Boys, is a double portrait of two teenagers wrongfully accused of assaulting a white woman. Regarding powerful personas is James Van Der Zee’s 1924 black-and-white photograph, Marcus Garvey in a UNIA Parade. Highlighting one of the earliest silent protests regarding murders and mob violence is a 1917 black-and-white photograph, “Silent Protest Parade on Fifth Avenue, New York.”

The exhibit ends on an upbeat note with a commanding eighteen-foot-wide mural which hangs alone in a spacious gallery. This six-paneled artwork, The Block, by Romare Bearden, was selected as the best suited work to pay homage to the Thinkers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance. This 1971 mural depicts the artist’s former Harlem address, which was located on a one-block row of five-story-buildings on Lennox Avenue between 132nd and 133rd streets. With vignettes that include a new-life with a baby in a stroller, or an end-of-life with pallbearers hoisting a coffin; to a Barber’s shop, to scenes where neighbours are gathered on the sidewalk or seated inside their apartments, each story continues to celebrate every aspect of Black life.

Left: Romare Bearden, The Block (Left Panel Detail of Six), 1971.

Right: Romare Bearden, The Block (Second Panel Detail from Left of Six), 1971. Photo Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From The Thinkers to Everyday Life and Portraiture, to Debates and Synthesis, to Language as Artistic Freedom, with Cultural Philosophy and History Painting, to The New Negro Artist Abroad, to European Modernism and The International African Diaspora, to Luminaries, to Nightlife, and Society, and to Artist as Activist, these expansive 160 artworks showcase the beginnings of an artistic counter narrative. The Harlem Renaissance marked the moment when African American artists “asserted pride in Black life and Black identity…and experienced this freedom of expression through the arts.” [4] This pre-World War II exhibit’s celebration of early twentieth century African American art confirms its long overdue legitimate presence in the American artistic landscape.

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism exhibition is on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art until July 28th 2024.

Footnotes:

[1] Douglas, “Notes from Aaron Douglas, “October 27th, 1949. Douglas Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

[2] Dr. Denise, Morrell, “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” March 7th, 2024. The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5vZ-x5G0Zs

[3] Tate Museum, German Expressionism, tate.org.uk

Lisa Black-Cohen

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED