PART 1: Friends and Relations: Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews @ Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill

In 1625 the English philosopher Francis Bacon wrote a collection of essays entitled ‘Of Friendship’ that celebrates the importance of intimate relationships. Specifically, he notes that the loneliest life is one devoid of friendship.

It seems almost too fortuitous that the name of this 17th-century philosopher is homonymous with one of the four artists comprising Gagosian Grosvenor Hill’s latest exhibition. Curated by art historian Richard Calcocoressi, the exhibit brings together the work of four stars within modern British art: Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews.

John Deakin, The Last Supper, 1963. Photograph: The John Deakin Archive/Getty Images. Left to right: Timothy Behrens, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews.

John Deakin’s iconic 1963 photograph of the foursome epitomises the life of friendship that Bacon philosophised. Comically titled The Last Supper, the photograph portrays the group (alongside Timothy Behrens, who makes an appearance in a portrait by Freud) wining and dining at mismatched tables in the Wheeler’s restaurant in Soho. However, the casual, cool banter captured by Deakin is only the tip of this much larger iceberg.

For the occasion, Gagosian put out all the stops to obtain the very best works by each artist. Comprising forty paintings, the exhibition features works from private and public collections, including loans from Tate Britain, the Sainsbury Center for Visual Arts, and Pallant House Gallery. In compiling little-seen works with public masterpieces, Gagosian successfully created a complete picture of the artists’ practices during this period.

Installation view. Left to right: Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud, 1964, and Michael Andrews, Melanie and Me Swimming, 1978–1979. Courtesy of Gagosian. Photo: Lucy Davis.

Rather than dedicating set spaces in the gallery to each individual artist as other curators might have done, Calcocoressi mixes work by the artists together. On one wall, one finds Bacon’s Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964) beside Andrews’ Melanie and Me Swimming (1978–1979) on loan from a private collection and Tate Britain, respectively. Another wall positions three reclining female nudes together - two by Freud and one by Auerbach. In doing so, Calcocoressi not only contextualises key works by each artist but, more importantly, illuminates direct connections between their respective practices.

Installation view. Left to right: Lucian Freud, Naked Girl, 1985-6; Lucien Freud, Naked Portrait on a Red Sofa, 1989-91; and Frank Auerbach, E.O.W, Nude, 1953-4. Courtesy of Gagosian. Photo: Lucy Dawkins.

This is most clearly seen in the portraiture on display. Undoubtedly the most featured genre in the exhibition - and in the artists’ oeuvre - the portraits provide the most precise picture of their shared artistic sensitivities.

Freud’s Father and Daughter (1949) is a haunting double portrait depicting the artist’s neighbour, Henry Minton, and his daughter simultaneously staring at the viewer with eyes glazed over. The inclusion of a blue and white beaded curtain that slightly obscures Minton’s face and both his arms - leaving the hand holding his daughter’s arm exposed - only intensifies this chilling portrayal of paternity. What a totally different sentiment from the warmer paternal love shown in Andrews’ Melanie and Me Swimming.

Lucian Freud, Father and Daughter, 1949. Oil on canvas, 91.5 x 45.7 cm. Private Collection. Courtesy Ocula. Photo: Annabel Downes, Ocula Advisory.

Self Portrait III (2021) by Auerbach is equally unsettling. Abstracting his own image, the artist presents an almost skeletal vision of himself. His unnaturally elongated neck draws one’s eye towards the hollowed face characterised by a vacant expression and further isolates his head from the imagined body beneath. The background of greens, yellows, pinks and purples have been mixed so hurriedly that they have almost blended together to create a dirty wash of colour reminiscent of a painter’s palette after a studio session. Set against this almost dirty background, the monochromatic paints that create the portrait itself stand out.

Frank Auerbach, Self Portrait III, 2021. Acrylic on board, 60.3 x 53.3 cm. © Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Geoffrey Parton. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Courtesy Gagosian.

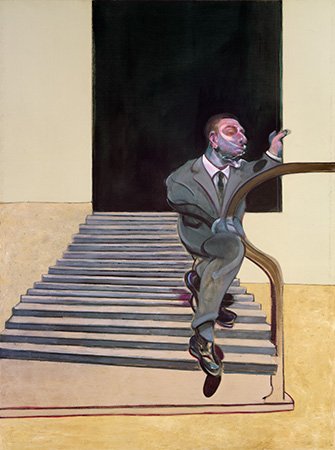

Portrait of a Man Walking Down Steps (1972) is a Bacon masterpiece. The portrait is a tender tribute to the artist’s late lover, George Dyer, who had died the year previously on the day before Bacon’s monumental 1971 retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris. As Auerbach masterfully does in his self-portrait, Bacon isolated Dyer’s head from the rest of his body and the surrounding environment by the strategic position of a Malevich-like black box.

Francis Bacon, Portrait of a Man Walking Down Steps, 1972. Oil on canvas, 198 x 147 cm. © The Estate of Francis Bacon.

Andrews’ group picture The Colony Room I (1962) presents the bohemian social scene of Soho in the 60s that attracted the artist and his friends. The dirty, smoky green interior suggests this is a world frozen in time, distant from both the viewer and Andrews as its painter. That Andrews was characteristically much more introverted and would escape London for a quieter life in Norfolk emphatically indicates this sense of detachment. Yet, this sense of outsiderness allows one to observe the partygoers more: Bacon, dressed in a hot pink shirt, casually leans on the bar; Deaken sits with his back to the viewer; artist’s model Henrietta Moraes occupies centre stage; Freud, with his piercing straightforward stare, is the only one to look out of the canvas.

Michael Andrews, The Colony Room I, 1962. Oil on board, 121.9 x 182.8 cm. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester. The estate of Michael Andrews / Tate Photo: Mike Bruce Courtesy Gagosian.

Just as Freud is the star of Andrews’ picture, he also is the central artist in the Gagosian exhibition. With more pictures on display than any of the other artists, the exhibition pins Freud as the glue of the group. Such weight is certainly appropriate given how Freud was the only one of the four that collected his friends’ work; it is known that he owned many paintings by Bacon, sixteen by Auerbach and one by Andrews. In highlighting these lesser-known details about Freud as a friend and artist, the exhibition brings a new perspective to the table laid with the other exhibitions staged to coincide with the centenary of Freud’s birth in 1922.

More broadly, it is exciting to not only see the pictures in conversation with one another, as if they were the artist personified but also to see how their histories connect through illuminations on the artworks’ provenance. Thus, one is presented with more than a surface-level view of friendship. Instead, Calcocoressi and Gagosian have developed a narrative of intimate connections. It reveals that, although the artists were in direct competition with one another, they shared a much deeper level of love and respect for each other’s practices than audiences might have expected.

Friends and Relations: Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews is on view at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, until 28 January 2023.

Ilaria Bevan

Editor in Chief, MADE IN BED