‘Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child’ @ Hayward Gallery

When encountering Louise Bourgeois' woven bodies, the viewer is accosted by stark materiality–the weave of the fabric and the masterful intercourse of textiles, each stitch meticulously succeeding the next. Her exquisite needlework is eclipsed only by the terrifically complex narrative behind each sculpture or painting, which remains subjective but undeniably carnal; limbless bulbous figures fornicating inside of glass vitrines, bodies suspended in space, and detached heads frozen in an intimate kiss.

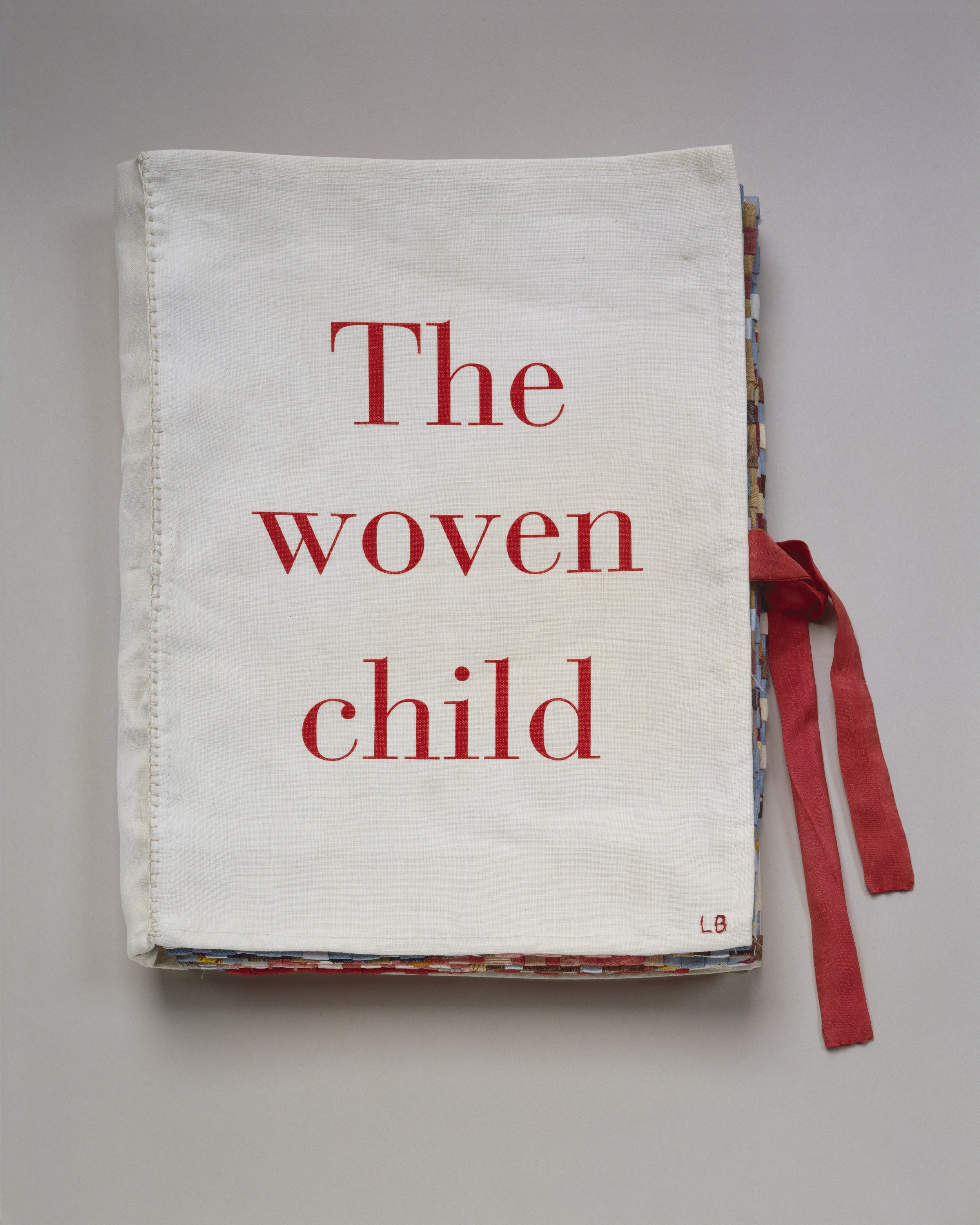

Her retrospective, The Woven Child, at London’s Hayward Gallery delineates her final years and her supreme incorporation of the textiles of her life. Don’t miss its last weekend on view, closing 15 May.

Louise Bourgeois, The Good Mother (detail), 2003. Fabric, thread, stainless steel, wood and glass, 109.2 x 45.7 x 38.1 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Christopher Burke.

Bourgeois is generally not difficult to come by. She was highly prolific and her work is exhibited regularly and frequently at exhibitions and fairs around the world. Just last week I encountered one of her vitrine sculptures at Whitechapel Gallery in East London. Lehman Maupin exhibited an entire wall of her paintings at Cromwell Place a handful of months ago. Her colossal spiders loom over pedestrians at the Tate Liverpool and Guggenheim Bilbao. What is so special, then, about this exhibition at Hayward Gallery?

Louise Bourgeois, The Woven Child, 2003. Fabric and colour lithograph book, 6 pages, 28.6 x 22.9 x 5.1 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Christopher Burke.

What makes this retrospective exhibition special is Bourgeois’ final surrender to material and the comprehensive incorporation of the materials of her life into the works during her final years. An avid, longtime hoarder of fabric–napkins, swatches, tablecloths, dresses, you name it, she collected it–and other materials, Bourgeois had a natural affinity with cloth. She loved clothes and outfitted her petite frame in velvety cream cotton and linen. Hoarding was conceivably the beginning of her process–a deeply personal practice that engaged sight, touch, smell, and memory. Many of the sculptures in the show are made directly from her and her mother’s wardrobes, demonstrating that the line between working materials and personal possessions became obscured if not imperceptible during her last years.

Louise Bourgeois, Couple IV, 1997. Fabric, leather, stainless steel and plastic, 50.8 x 165.1 x 77.5 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Christopher Burke.

Rather than engaging with material as an object or a surface, her exploration of matter was a stage on which to act out the means of production; examining corporeal boundaries and the materialising effects of domination. Her analysis invariably resulted in a seemingly insatiable exploration of gender and sex. This provoked questions like, how is sex materialised? What did that look like through the eyes, or hands, of the artist? What is the matter of sex?

Louise Bourgeois, Single I, 1996. Fabric, hanging piece, 213.4 x 132.1 x 40.6 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Ron Amstutz.

The academic association of matter to femininity can be linked with an etymological connection that originates from ‘mater’ or ‘mother’[1] and the womb as an original site of production and reproduction. Bourgeois’ enduring fascination with the womb can be seen time and time again, whether through literal paintings of uterine environments or three-dimensional installations like her series of lairs. These domicile-like structures are cages encasing figures and objects, but can also include organ-like sacs and other cocoon bodies. The womb emerges not only as a place of production or growth but as an all-embracing destination for shelter and safety.

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1997. Steel, tapestry, wood, glass, fabric, rubber, silver, gold and bone, 449.6 x 665.5 x 518.2 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Maximilian Geuter.

“The lair is a protected place you can enter to take refuge. And it has a back door through which you can escape. Otherwise it’s not a lair. A lair is not a trap.”

Through sculpture, Bourgeois developed a practice of reparation–both on a material and psychic level. Even her larger, non-textile works portray reparative actors. Her iconic steel spiders, for instance, who tower over the viewer, were born from her admiration of the spider as a weaver and a repairer, whose delicate web is constantly bashed and mended. Her mother and father were tapestry restorers in Paris, and from a young age, she assisted in the family business by drawing the missing parts of patterns and learning how to sew. She recounted her childhood as traumatic, singed by the emotional distress of her father’s extramarital affair and the premature death of her mother.

“Sewing implies repairing. There is a hole...you have to hide the damage...you have to hide the urge to do damage...the something bad you have done must be undone. I sew...I do what I can. This goes back to my mother...she repaired things...she repaired everything.”

Louise Bourgeois, In Respite, 1992. Steel, thread and pigmented rubber, 328.9 x 81.3 x 71.1 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Serge Hasenböhler.

Her exploration of gender is embedded in her objects, which despite entering the realm of abstraction, walk a fine line between what the normative mainstream wants to classify as either masculine or feminine. Testicular pouches droop neutrally next to globose, perky lumps, embracing their objecthood, yet they could easily be read as breasts or buttocks, depending on who you ask, or perhaps neither. She has allowed them to be objects of their own fruition, leaving the viewer to reevaluate his or her own preconceptions and experiences. In this sense, Bourgeois achieves to turn the tables on vulgarity, leaving us to assume responsibility for our own inherent objectification and innermost perversions.

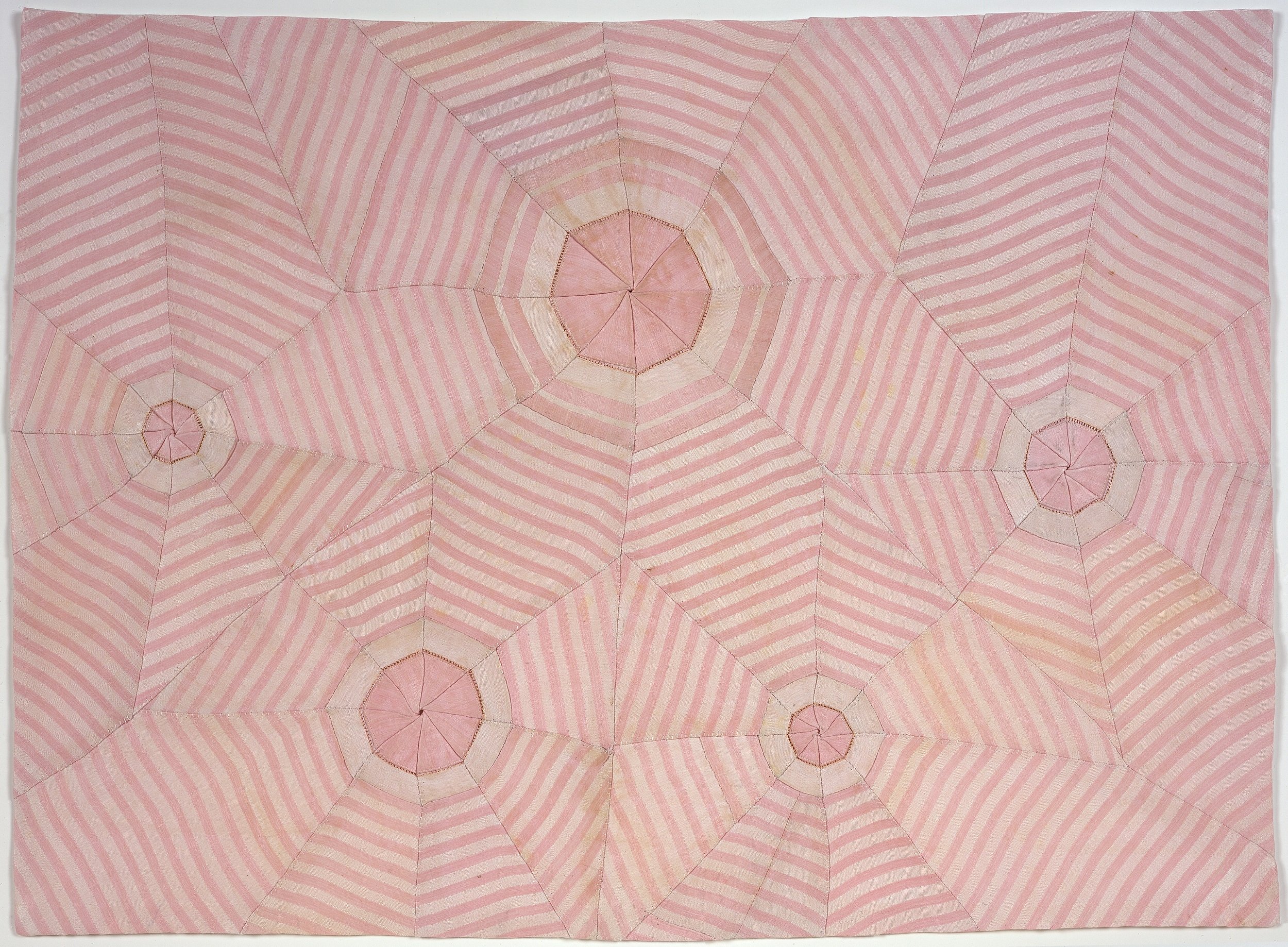

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2007. Fabric, 54.6 x 74.9 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Christopher Burke.

Each tear or stitch has a psychic equivalent. The act of rehabilitation was curative to her psychological wounds, as her reparations occurred inside as much as outside the body. Her process begs the question of whether material existence is separate from thought, or if materiality must be tied to an object at all. Can consciousness extend to objects outside ourselves? For Bourgeois, materiality was a practice which originated first in her psyche, obscuring the distinction between material and cerebral reformation.

“When does the emotional become the physical? When does the physical become the emotional? It’s a circle going round and round.”

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2002. Tapestry and aluminum, 45.7 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo by Christopher Burke.

For an artist who is arguably best known conventionally for her metallic, colossal figures, the exhibition offers a rare meditation on the rich diversity of her softer works and watercolours. She was exceptionally skilled with her hands as well as conceptually innovative, something we see less and less of in the new millennium, and garnered acclaim as a young adult in a world that devalued female artists even more than today. Even then, her work minted her as outspoken and provocative; fearless, a powerhouse, and an icon. Bourgeois never stopped working and lived until she was 98. The cyclical nature of her production suggests that perhaps her courage came from the artworks themselves, and vice versa.

References:

[1] Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter, 1993.

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child is on view until May 15 in London’s Hayward Gallery at the Southbank Centre.

Camille Moreno

Features Co-Editor, MADE IN BED