Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life @ Tate Modern

Visitors are gifted with a transcendental view of the natural world in Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life at Tate Modern. This exhibition does not present the abstracted forms of the two artists as a rejection of representation, but instead as a mode of expression.

Af Klint, the Swedish pioneer of abstraction, takes the viewer on a journey through all processes and forms of life, from natural geometry to the human soul. Similarly, Mondrian distils organic forms into his quintessential solid lines and blocks of colour. While af Klint and Mondrian never met, their works touch on many of the same themes of mysticism, Theosophy, and nature. The exhibition draws a remarkable parallel between the artists allowing the viewer to immerse themselves in two connected yet separate world views.

Hilma af Klint, Lake Scene (Undated). Oil on canvas. 24 x 37 cm. Source: Author.

The exhibition begins by beautifully juxtaposing some of the artists’ earliest representational works, which hint at their evolution into spiritualism and conceptual abstraction. Af Klint, who trained as a landscape painter at the Stockholm Academy of Fine Arts in the 1880s, displays her prowess for realist representation in her painting Lake Scene (undated). Here, a winding path disappears around a bend and an idyllic lake is seen in the distance. At this early stage of her artistic career, af Klint masterfully represents this landscape in a muted realist style that is different, but not wholly opposed, to her later mystical works.

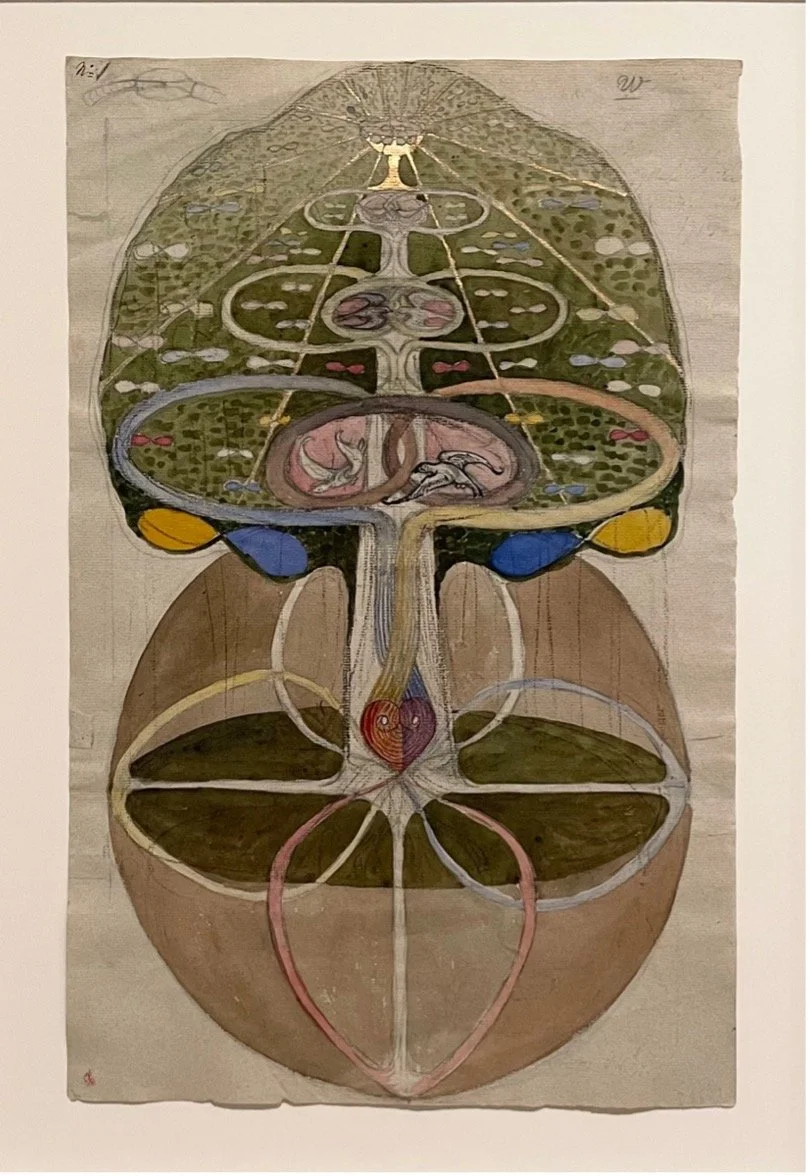

Hilma af Klint, The Tree of Knowledge, No. 1 (1913-17). Watercolour, gouache, graphite, and ink on paper. 45.8 x 29.5 cm. Source: Author.

More specifically, af Klint’s origins in representational painting styles are wonderful to consider when viewing her later works. This is especially true of her series The Tree of Knowledge (1913), which addresses earthly life through the conceptual lens of the axis mundi and its connection to the spiritual realm. In The Tree of Knowledge, No. 1, af Klint represents the mythical world tree in a tangled knot of roots and branches. These twisting lines connect the tree to the earth and the glimmering golden cup of the heavenly realm above. Af Klint’s grasp of form and design grounds the image while transcending all earthly representation. Her care for and interest in natural life extends from her early landscape paintings into a more esoteric understanding of the processes of life. With this juxtaposition, the exhibition effectively questions traditional modes of representation, specifically the shape of our natural world. Undoubtedly, this is the most compelling theme of the exhibition, as the conversation between the artist’s work provides a new lens through which to understand the symbolism within abstracted forms.

Piet Mondrian, Haystack Behind a Row of Willows (1905). Oil on Canvas. 29 x 37.5 cm. Source: Author.

Similarly, Mondrian’s early works produced during his Hague School period are heavily influenced by ideas of traditional representation. His painting Haystack Behind a Row of Willows (1905) captures nature in rough brushstrokes and deep greens and browns. Not completely Realist, Mondrian’s painting bears an Impressionistic quality evidenced by the less defined borders and lines, as was typical of Dutch painting at the time. Though Mondrian utilises a recognisable form of representation, the technique he used is a form of abstraction by capturing a moment in time. Even at this early point, his interest in creating a unique understanding and representation of natural life is clear and translates well into his later works.

Piet Mondrian, Flowering Apple Tree (1912). Oil on Canvas. 78.5 x 107.5 cm. Source: Author.

As with af Klint, the exhibition soon compares Mondrian’s early works with his later abstract representations of nature. In his work, Flowering Apple Tree (1912), the form of the tree is evoked through black swooping lines resembling branches and ellipses that resemble leaves. However, outside these formal comparisons, little about the tree is recognisable. The representation here is merely conceptual, signifying the tree’s character instead of its form. In these visual comparisons, the exhibition spotlights Mondrian’s interest in a higher understanding of the natural world, unrestricted by traditional modes of representation. Thus, his work mirrors af Klint’s own esotericism displayed in The Tree of Knowledge. As reiterated throughout the exhibition, Mondrian’s apple tree is more engaging when viewed with his earlier work as it develops a deeper symbolic understanding.

Hilma af Klint, No. 19 (1914-15). Oil on Canvas. 148.5 x 152 cm. Source: Author.

As one progresses through the rooms, af Klint and Mondrian’s interest in mysticism and Theosophy is deepened. This pulls their works further away from the initial realist landscapes towards the spiritualism and complex planes of knowledge their work is known for. In No. 19 (1914-15), af Klint displays her interest in geometry and the ability of pure shapes to represent greater spiritual enlightenment. In this painting, a pink and white nautilus shell is positioned on top of a colour-block background. As the shell spirals into the centre of the work, it simultaneously emerges from and recedes into the background. While af Klint’s piece speaks to her current fascination with spiritualism, it is clear that her initial interests in the natural world have not been forgotten. Her representation of the nautilus shell, which is both mathematical and perfectly natural as a hallmark of sacred geometries, merges these two themes.

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow, Blue, and Red (1937-42). Oil on Canvas. cm. Source: Author.

In Mondrian’s later work, his prototypical compositions of black grids with colourful blocks arise as icons of Neo-plasticism. This subsect of Cubism developed by Mondrian aimed to represent what he called “pure reality.” Here, the natural world was distilled into its basic forms and colours. Vertical and horizontal black lines intersect in Composition with Yellow, Blue, and Red (1937-42), and primary colours fill four spaces in the grid. In this work, Mondrian aspired to a higher understanding of nature and reality through elementary colours and patterns. Thus, much like af Klint’s spiritualism, Mondrian found a more esoteric truth in the essential manifestation of nature, which he achieved in this fine example.

Hilma af Klint, Group 4, No. 3 The Ten Largest, Childhood, (1907). Tempera on paper. 3.28 x 2.4m. Source: Tate.

Fittingly, the exhibition concludes in room ten with af Klint’s Ten Largest series. The paintings in this room, standing at 3.28m high, tower over the viewer with their vibrant colour and dynamic form. As with much of af Klint’s work, these works must be understood in series and not as ten solo pieces. However, one work which stands out above the rest is Group 4, No. 3, Childhood (1907). With its flaming orange background, the piece draws the viewer’s eye and entangles them in its web of interlacing abstracted forms. Af Klint’s signature nautilus shells and spiralling forms dance on the canvas, bounding along the delicate lines that connect them. This movement creates harmony with the other paintings in the series and ultimately opens a dialogue between spirituality and nature that is utterly compelling.

Fundamentally, the exhibition aims to transport the viewer to a new plane of seeing; it succeeds in this goal on every level. By comparing the early techniques of af Klint and Mondrian, one reconsiders the place of abstraction among other representational styles as well as the many forms abstraction can take. This is built upon by the carefully crafted conversation between the early and later works of two seemingly unrelated artists championing differing interpretations of abstracted form. Both on their own and in dialogue, the works by af Klint and Mondrian are spellbinding representations of the natural world and the invisible spiritual realm that will entrance and intrigue anyone visiting the exhibition.

Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life is on display Tate Modern until 3 September 2023.

Maria Whitby

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED