Banksy: Cut & Run @ Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art

Banksy’s solo show at the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) represents a contradiction between art and experience that comes with today’s art exhibition spectacles. Banksy: Cut & Run presents a selection of his stencil pictures from 1988 to the present day and, with them, a unique insight into the illusive artist. Wildly popular, the show has extended opening hours on the weekend, running from 9am Friday until 5am Saturday, turning what might have been a traditional retrospective into a rare opportunity to experience a museum in the early hours of the morning.

The sold-out show was almost inaccessible but for the late-night openings, so when queuing on the steps of GoMA at 2 o’clock in the morning, one begins to wonder if the goal of the exhibition is to display art or to create a sensationalist activity. Arguably, this is the ultimate point of Banksy’s work, as it upends the audiences’ expectations of art and society. However, as a visitor, this nature challenges one’s ability to experience the exhibition in a traditional mindset.

Exterior view. Gallery of Modern art. Via GlasgowLife

Upon entering, visitors must seal their phones and any cameras in lockable pouches as the exhibition has a strict ‘no photography’ rule. Whilst this act undoubtedly was enforced keep Banksy’s secrets within GoMA’s walls, this stringent regulation seemed out of place, especially within a solo exhibition of a famously anti-establishment artist who encourages photographic sharing of his media. Further, Banksy’s street art, which he gained his initial fame from, is inherently public and is therefore available to be seen and photographed by all. Thus, one might have expected that the exhibition would be a free-for-all of photography and interaction. Setting this tone of tightly regulated involvement, therefore, created a contrast between the experience and the art.

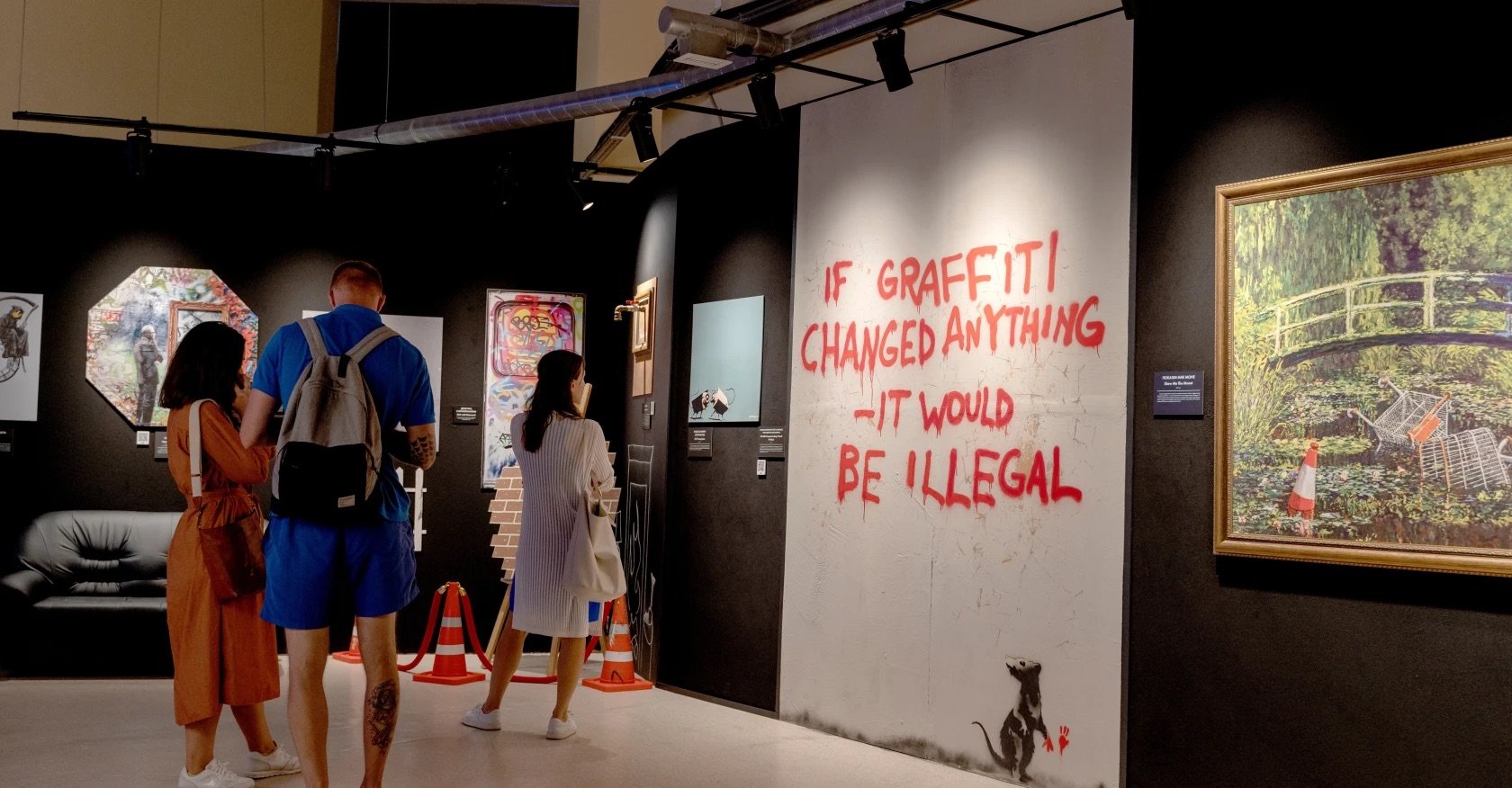

Of the actual viewing experience, the exhibition was extremely constructed, and viewers were encouraged to move quickly through each room. Banksy’s stencils were displayed alongside photographs of his work on display around the world, giving an overview of his career, the international reach and the materiality of his work. All the wall text was written from Banksy’s perspective using trademark casual and witty language. Thus, instead of reading the typical dull tonality of a museum text, it felt as if the disembodied voice of the artist was speaking to the visitors. In doing so, his anonymous persona felt present and aligned completely with the Banksy image making it perhaps the most innovative part of the entire experience. Walking through Banksy’s history from 1998 to the present day, it was exciting to learn the artist’s thoughts and ideas behind some of his most famous works through his personal lens whilst still maintaining his anonymity.

Visitors in Banksy: Cut & Run. Photo Ultraskip/Shutterstock. Via AFAR.

In his texts, Banksy also credits the larger team and networks that help him create his works – a rare moment of acknowledgement in a celebrity-driven art world. For example, he reveals how he recruited a friend to buy out-of-commission police equipment when designing Stormzy’s stab vest, revealing the importance of collaboration in his work, in a continued effort to keep his identity a secret. This was a significant choice as it pushes the image of Banksy away from the lone and mysterious artist and more towards that of a regular artist who collaborates with friends to create art. Thus, the entire exhibition de-mythologises the artist, in turn grounding his image in reality and removing some of the mystery around his process.

One of the most fascinating inclusions in the exhibition was the design and development behind the infamous shredded Girl with a Balloon (2006) that was sold at Sotheby’s, London, in 2018. The exhibition reveals never-before-seen intricate technical details behind the stunt as well as displaying one of the artist’s test pieces. For an event that so greatly enthralled the art world, it was thrilling to see how the piece came to be and how much trial and error went into making the destruction happen.

Banksy, Going, Going, Gone. Photo: Jane Barlow. Via Edinburgh News.

With all these experiential elements and personal insights into the artist’s process, the actual stencils and works of art seemed secondary within the entire exhibition. They served as more of a backdrop against which Banksy’s story was told and were presented as supplementary evidence of who he is and what forms his process takes. With no photography allowed, only the memory of which works were on display and the stories around them remained, adding exclusivity to the curated show. This removed the temptation to be distracted by capturing the perfect picture for social media but also contrasts with the public availability of street art.

The exhibition was truly about the overall experience, fitting into a larger trend of interactive and immersive exhibits. Yet, for all its innovations, in the grand scheme of immersive exhibitions currently taking place around the UK and internationally, it is not clear if the Banksy show hit the mark. While it is a fascinating look into the artistic process and work of the artist, certain elements of the show seemed misaligned with Banksy’s overall thesis. However, perhaps this is more indicative of how Banksy’s works inherently clash with the act of institutionalisation and the museum setting rather than the streets as he originally intended.

Ultimately, there are elements of the Banksy show which can be problematised against the artist’s message. However, this is also the most redeeming part of the show. The audience is given the space to decide whether these are intentional elements put on by the artist, thus furthering his campaign of institutional critique, or if the exhibition is another feather in the cap of a long roster of ‘sell-out’ artists who have turned socially attuned works into a spectacle for the masses.

As stated by the artist himself, this show is possible now because he no longer faces any risk of criminal charges due to the position and content of his street art. Banksy’s public works can be held under vandalism laws as they are created on public or private property without permission. The stencils which are on display in GoMA could, at one point, have been used as evidence against the artist; however, with the cultural validity provided by the museum setting, his works have clearly exited the sphere of rebellion and are now truly considered art. But with this newfound seat at the socially accepted art table comes the potential price that the impact of Banksy and his works has been dampened, especially within museum settings such as GoMA. Nevertheless, his works continue to encourage viewers to ask questions about the place of art in society, the commercialisation of the art world, and our place within the larger establishment.

Banksy: Cut & Run Exhibition Poster © Banksy 2023. Via My Art Broker.

With this, the opinion is final: as an exhibition, Cut and Run was unique, as it brings into question Banksy’s position as an artist and the true intention behind his works and stunts. Our tip? Go in the middle of the night for an even heightened experience.

Banksy: Cut and Run is on display at the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art until August 28, 2023.

Maria Whitby

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED