Past = Present? Cy Twombly’s Nine Discourses on Commodus and Charles Olson’s New Humanism

“What I am trying to establish is – that Modern Art isn’t dislocated, but something with roots, tradition and continuity.”

Cy Twombly’s Nine Discourses on Commodus (1963) is a work commonly overlooked in the artist’s oeuvre. Akin to the artist’s other works created during the period of 1962 to 1963, Nine Discourses depicts a historical assassination, that of Roman Emperor Commodus Aurelius. This funereal nature of Twombly’s work was undoubtedly motivated by the funereal atmosphere of contemporary America, whether that be the escalation of Cold War tensions, the Cuban Missile Crisis, or the recent assassination of President John F. Kennedy (JFK). This conflation of Ancient Rome and the social and political climate of the 1960s ultimately resulted in the creation of an allegorical history painting.

An analysis of Nine Discourses through the lens of New Humanism, a critical movement taught by Twombly’s mentor, Charles Olson, offers a new lens through which to read this work. The New Humanist encouragement of participatory intervention allows the past, present, and future to penetrate each other and emboldens viewers to discern the relationship between them – the destructive nature of mankind’s desire for power.

Cy Twombly, Nine Discourses on Commodus, 1963. Source: Guggenheim Bilbao.

Permanently displayed in the Guggenheim Bilbao, Twombly’s Nine Discourses on Commodus is a singular work comprised of nine individual canvases. The cycle spans an entire wall, creating an overwhelming visual experience of abstraction. Despite its complete lack of figuration, the work’s emotional and visceral mark-making generates an impression of chaos and violence that only an abstract image could convey. Such themes are extremely appropriate in reference to the cycle’s homonymous character, Aurelius Commodus. Commodus served as the last Emperor of the Nerva-Antoine dynasty, ruling from AD 180 until his death in AD 192. As his reign progressed, he became increasingly tyrannical and psychologically unstable, precipitating his assassination and the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire. The nine canvases, each measuring the same size and sharing a pale grey background, act as a baseline system of measurement by which to understand the abstract forms seen throughout the cycle: the whorls, which grow in size and layers of paint reflect the escalating pandemonium characteristic of Commodus’ regime.

This painterly reconstruction of violence and mayhem was influenced by Twombly’s observation of a similar situation which was unfolding in America – the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and JFK’s assassination. The escalation of Cold War tensions originated in the binary rhetoric of American capitalism versus Soviet communism, a discourse which provoked severe paranoia and disarray in the psyche of the United States public. This mass hysteria, also known as the Red Scare, was exacerbated by the politician Joseph McCarthy; his ‘reign of terror’ created a climate of fear and repression that would linger across the nation for years to come. These phenomena of conflicting ideologies and social pandemonium are also apparent in the formal qualities of Nine Discourses: the two whorls of paint seen throughout the cycle may be read as a symbol of the conflicting discourses of capitalism and communism. Moreover, while the chaotic mass of colours and painterly gestures exemplifies Commodus’ progressively tyrannical style of governance, it equally represents the social pandemonium incited by McCarthy. From this contemporary historical reading, it is clear that Twombly believed McCarthy to be a modern-day Commodus. This conclusion is additionally strengthened by the growing presence of the thick splashes of scarlet paint throughout the cycle, emblematic of the fear of a growing ‘red’ hegemony.

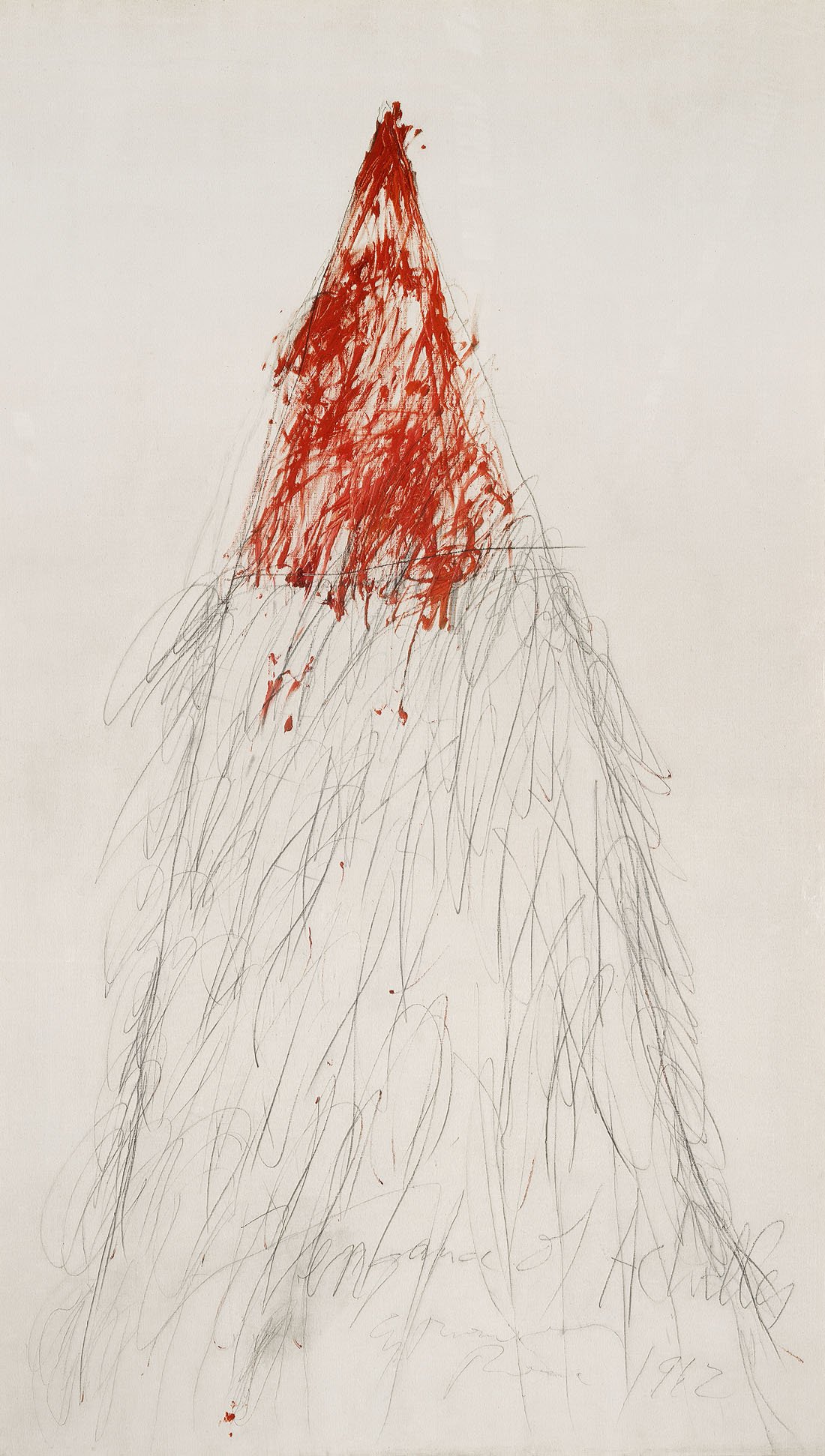

The contemporary anxiety surrounding the Cuban Missile Crisis can also be read in Nine Discourses. By 1949, both the Americans and the Soviets had successfully developed and tested the atomic bomb, and by the mid-1960s both possessed ample weaponry to annihilate the world’s population. This threat of an imminent nuclear apocalypse left a significant mark on Nine Discourses, with modern innovations in rocketry indicated by the triangular shape seen in Commodus IV. This shape recalls Twombly’s Vengeance of Achilles (1962). While Twombly first produced this bloodied javelin shape as a commentary on Achilles’ rage, he also noted its visual similarity to a fiery rocket. [1] This conflation of ancient hand-to-hand combat and long-range nuclear war possibly aimed to expose the latter’s primitive nature to create a visual language of contemporary anti-nuclear protest. Once again, Twombly employs the past to comment on the present.

The final historical event to inform Nine Discourses was the assassination of JFK. In addition to the obvious pertinence of the subject of assassinated rulers, media coverage of the President’s murder had a significant influence on the cycle’s formal qualities. Certainly, Twombly would have seen the images of JFK’s assassination, captured on film by Abraham Zapruder and distributed worldwide. The sequential nature of the Zapruder film may have acted as a model for the chronological nature of Nine Discourses, with the choice to exhibit the work in nine parts bearing a striking resemblance to Zapruder’s nine stills published in Life magazine. [2] As the President’s assassination occurred a mere month before Twombly began work on Nine Discourses, it has been questioned whether this incident actually served as an influence. However, the cycle’s emphasis on sequence and the ratio of nine offers a visual language previously unfounded in Twombly’s oeuvre. As such, it is reasonable to assume that Nine Discourses took inspiration from this specific historical moment.

Stills from the Zapruder film, 1963 (renewed 1995). Source: The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza.

Undoubtedly, Twombly “succeed[ed] in bringing myths into the present and integrating their residues in art... thus underscoring their ongoing significance and topicality.” [3] By insisting that history is not a linear and static phenomenon but instead one that is actively and constantly renegotiated, Twombly conforms to the fundamental principles of Charles Olson’s New Humanism. The pair first met during their time at Black Mountain College, a private liberal arts college in North Carolina. Olson, the College’s rector, first conceptualised this reformation of Humanism in 1951; in his essays ‘Project Verse’ and ‘Human Universe’ Olson called for “another humanism” due to his dissatisfaction with Old Humanism’s binaries of experience and logic, body and mind, and signifier and signified. He believed these distinctions acted as a barrier between experience and expression, thus leading humans to become estranged from their own bodies and nature. New Humanism, therefore, worked towards restoring an immediacy to human consciousness and fully contextualising the individual within the “rolling, curving, contingent reality.” [4]

New Humanists believed that if one could locate this relationship, then insight could be gained into a set of universal, timeless conditions. Indeed, Nine Discourses succeeds in not simply recreating the past but insisting upon its essential link to the present. In likening the modern historical situation to the period of Commodus’ reign, viewers can see their inherent similarity – mankind’s unrelenting violent nature. The allegorical relationship between Imperial Rome and 1960s America suggests that both governments had created situations of inescapable violence for their subjects. Through the lens of Olson’s New Humanism, viewers can understand that they are not retrospectively looking back at a history of violence but are active partakers and instigators in it. The synthesis of Commodus and McCarthyism alongside javelins and rockets furthers this impression, urging viewers to learn from past mistakes and comprehend the futility of violence and aggression. In locating this archetype of destructive human behaviour in primitive society, Twombly hopes to protect America from a state of ruin that defined Commodus’ reign. As Olson critically evaluated society’s failure to appreciate and understand the past, so too did Twombly.

Twombly is famously remembered to have said, “What I am trying to establish is – that Modern Art isn’t dislocated, but something with roots, tradition and continuity.” [5] By using Olson’s concept of New Humanism to analyse the cycle of Nine Discourses, one can say with absolute certainty that he succeeded.

Cy Twombly, Nine Discourses on Commodus, 1963. Source: Guggenheim Bilbao.

To discover more about Cy Twombly’s Nine Discourses on Commodus (1963), please visit the Guggenheim Bilbao’s website.

Footnotes:

Mary Jacobus, Reading Cy Twombly (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2016), 108.

Nicholas Cullinan, “Nine Discourses on Commodus, or Cy Twombly’s Beautiful “Fiasco”,” in Cy Twombly,

ed. Jonas Storsve (Paris: Sieveking Verlag, 2017), 78.

Michael Schreyach, History and Desire: A Short Introduction to the Art of Cy Twombly (San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Coates Library, 2017), 49.

Carol A. Nigro, “Cy Twombly’s Humanist Upbringing,” TATE Papers no. 10, Autumn 2008, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/10/cy-twombly-humanist-upbringing.

Christine Kondoleon and Kate Nesin, Cy Twombly: Making Past Present (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: MFA Publications, 2020), 11.

Emily Males

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED