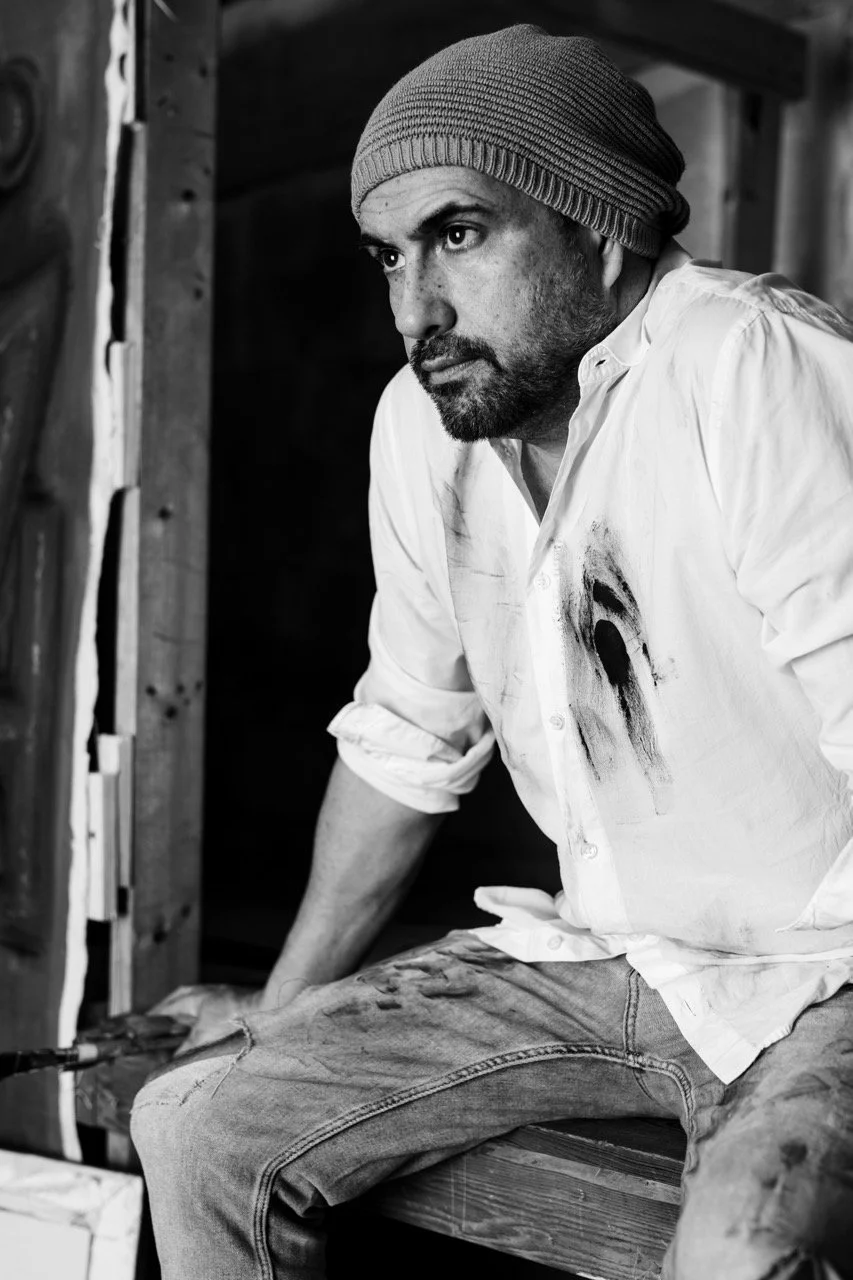

María Paula Suarez in Conversation with Independent Curator, Ibis Hernández Abascal on the Enigmatic Paintings of Christian Santy

Ibis Hernandez Abascal was part of the founding team of the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center, where she has been working since 1985. She has co-curated nine editions of the Havana Biennial between 1994 and 2019. She received the National Curatorship Award, granted to the collective of the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center curators for their work between 1989 and 2000.

In this exclusive interview with MADE IN BED Magazine, Ibis elaborates on her input regarding the body of work made by Christian Santy, shares her perspective on the contemporary art scene, particularly within the context of Cuban art through Santy’s lens, and explores the artist’s merging style that bridges abstraction and figuration. On these topics, Ibis Hernandez sheds light onto Santy’s fresh and thought-provoking artistic practice, in which he reflects on how we navigate our individual and collective histories by simultaneously exploring his personal experiences and reflecting on ideas about identity and migration.

María Paula Suárez: You collaborated with Christian Santy's studio during the last months of 2022 and the first months of 2023. How did you become familiar with this artist's work?

Ibis Hernández Abascal: I learned about his work through Marilyn Sampera, a Cuban curator who was organising a solo exhibition of Santy in mid-2022, and Dannys Montes de Oca, an art critic also from Cuba, who wrote a text for the catalogue. I got in touch with the artist in Miami shortly before that exhibition opened in Havana. Santy was born in Cuba in 1973 and emigrated to Miami in 1994. Although he never stopped painting, Santy did not have the same success as other Cuban creators of his generation who graduated from art schools on the island. While Santy remained in the shadows, his contemporaries achieved early visibility in Cuba and abroad. This success was brought about when, in the 1990s, various taste-impacting factors coincided with the growing interest in local production, critical reception, international circulation, and market integration of Cuba’s national art. I suppose that's why I didn't have the opportunity to become acquainted with his work earlier.

MPS: What can you tell us about Santy’s artistic education?

IHA: Santy's educational process did not follow the usual pattern of academic training. The sources of his knowledge have primarily been his confrontation with the work of great Master of Art History during his visits to museums and galleries in different countries, as well as his participation in some courses that have provided him with the necessary tools to practice painting in contemporary times.

MPS: How would you generally characterise Santy's work?

IHA: Santy edges the boundary between abstraction and figuration as part of an analysis of painting that goes beyond purely formal research to find in the possibilities of the medium the production of the meanings he intends to convey. Indifferent to the unproductive dilemma of representing or not representing his creative process unfolds without concern for the borderline between both possibilities, leaning towards one side or the other according to the dictates of his own intuition and sensitivity and in relation to the subject he addresses.

MPS: Can you expand on what these subjects include?

IHA: In his work, Santy reflects on topics that have already been addressed in the history of Cuban art over the last three decades, such as the insular condition, personal and collective memory, and migration, among other issues that converge in thoughts about identity and the nation.

MPS: Would you classify Santy's work within any particular abstraction movement?

IHA: Santy's art dances with geometric abstraction, using shapes reminiscent of geometric figures but not strictly adhering to their rationality. The interplay of these forms evokes landscapes and objects while subtle figurative elements connect to the external world. Notably, these elements vary in prominence and sharpness. A closer look at the canvas reveals the cartographic configuration of Cuba, fragments of patriotic symbols, tiny human figures, and meaningful words. Santy also explores alternative modes of abstraction, drawing inspiration from distant memories. Titles and graphic elements in his compositions extend beyond formal concerns. Overall, his art beautifully blends abstraction with diverse artistic approaches.

MPS: You previously mentioned that Santy's work addresses migration, among other themes, which has been present in the work of other Cuban artists through recurring imagery, including passports, oars or suitcases. Does any other recurring symbol or figure appear in the treatment of this theme in his work?

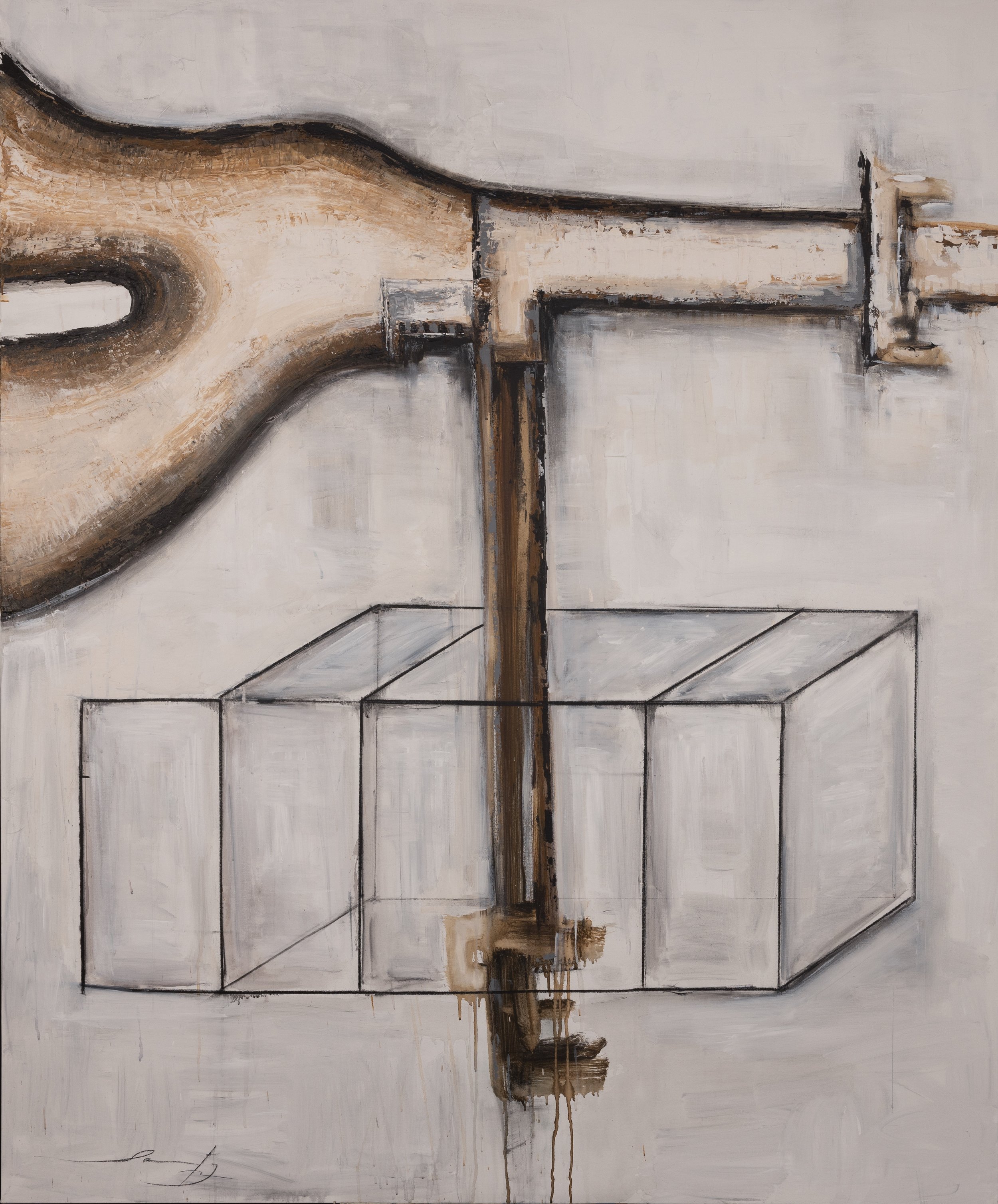

IHA: Santy's artwork delves into the theme of migration through the symbolic path. In pieces like Travesía (2019) the Nicaragua inscription symbolises people's journeys toward the United States. The path, depicted with barbed wire-like lines, portrays routes with uncertain destinations. Migration exploration extends to existential themes of loneliness, freedom, and fear, evident in La Soledad Infinita (2022) and Viaje a lo Desconocido. The human figure plays a pivotal role in these artworks. Additionally, pieces like Combinaciones, La llave del éxito (2015), and Encrucijada combine the path's image with a free and distant representation of a wrench's realistic pattern. Santy's works skillfully incorporate human figures and symbols, revealing the dynamics of life's journey.

MPS: You mentioned that Santy's work sits on the border between abstraction and figuration. How does his work behave when it leans more toward figuration?

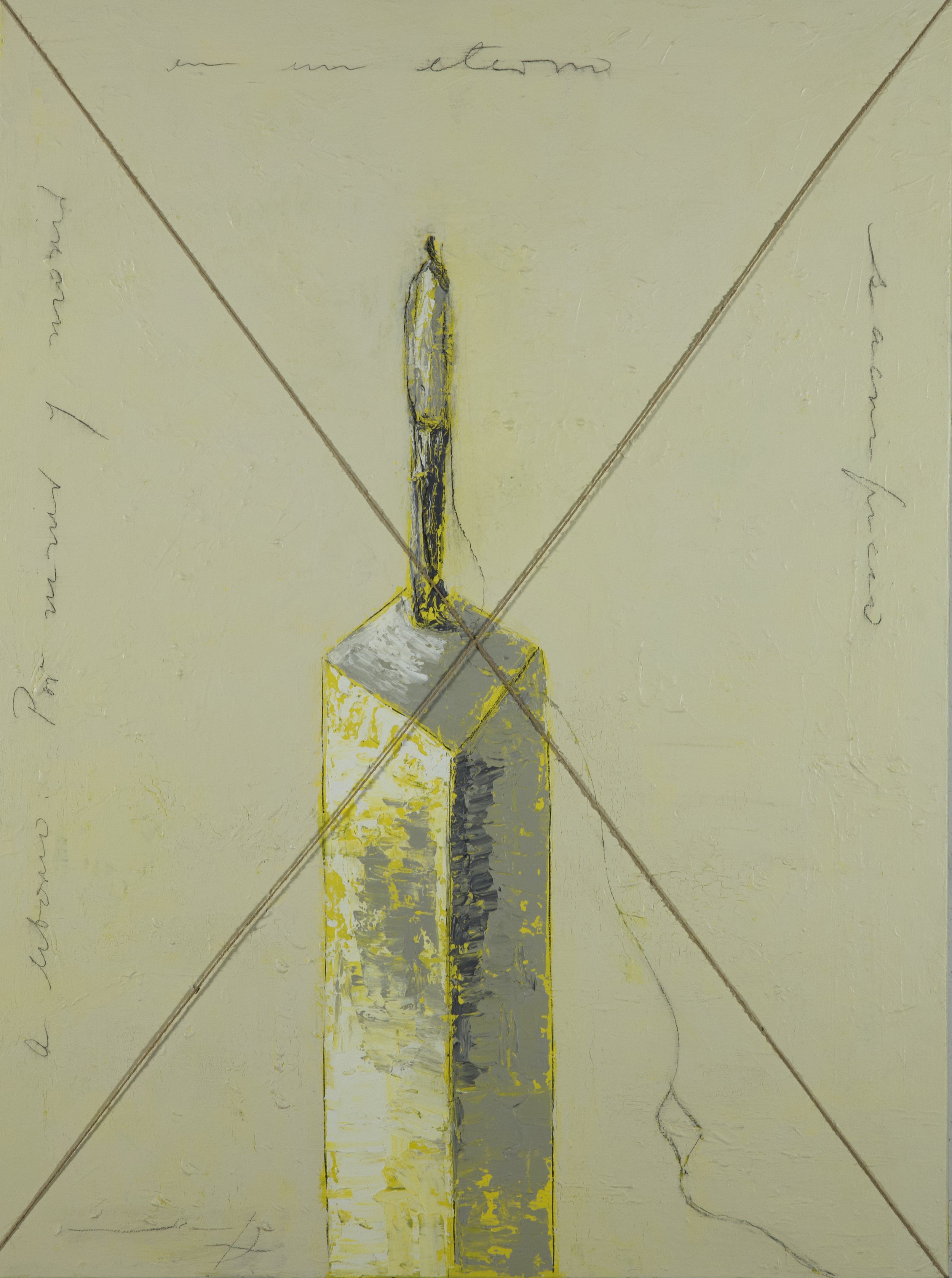

IHA: When Santy's work leans towards figuration, recognisable geometric forms are incorporated into objects found in immediate reality. In La jaula (The Cage), for example, the object's configuration is represented by a few lines on an octahedral-shaped element resembling a plinth. The simplification of the image serves a purpose beyond form and synthesis. The cage symbolises mental structures that paralyse and confine, it is in a state of false comfort and those structures keep him from going out of the cage. The presence of a confined bird, depicted with loose brushstrokes, raises questions about its voluntary or involuntary captivity. Furthermore, the inclusion of text in the upper right corner provides insight into mechanisms used by power to restrict freedom in totalitarian regimes.

La jaula, 2021, Acrylic on canvas, 70,9 x 59 in.

Precipicio, 2022. Mixed media on canvas, 59 x 82.6 in.

MPS: Although Santy has primarily developed his work through painting and drawing, he has occasionally experimented with other artistic expressions. What can you tell us about this?

IHA: Santy's artistic exploration goes beyond traditional painting and drawing. He ventures into installation art using cut-out wooden figures to create contextual settings, which he continues to develop. Recently, he has delved into audiovisual art, showcasing his debut piece Pionera (Pioneer). The video incorporates the iconic red scarf of the Unión de Pioneros de Cuba (UPC) tied to a structure resembling an unfinished monument amidst a desolate and disaster-stricken scene. This thought-provoking artwork questions the fate of the revolutionary ideal of the "new man" and the pioneer's role. The presence of the scarf in such circumstances introduces ambiguity and opens the door to utopian interpretations.