A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography @ Tate Modern

Situated on the second floor of Tate Modern, A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography provides viewers with works from thirty-six artists to reimagine the lived histories of Africa. Divided into three chapters spread across multiple rooms, the exhibition highlights the inclusion of African photography into the zeitgeist of Art History.

With subjects stretching across traditional histories, belonging and displacement, the archive, and geographical ecology, this blockbuster exhibition has already proved to be one of the must-see exhibitions of the year.

Curated by Osei Bonsu, the exhibition provides viewers with a comprehensive, accessible, and thought-provoking celebration by spotlighting a medium from regions that have historically been overlooked.

View from one of the exhibition rooms. Image: the Author.

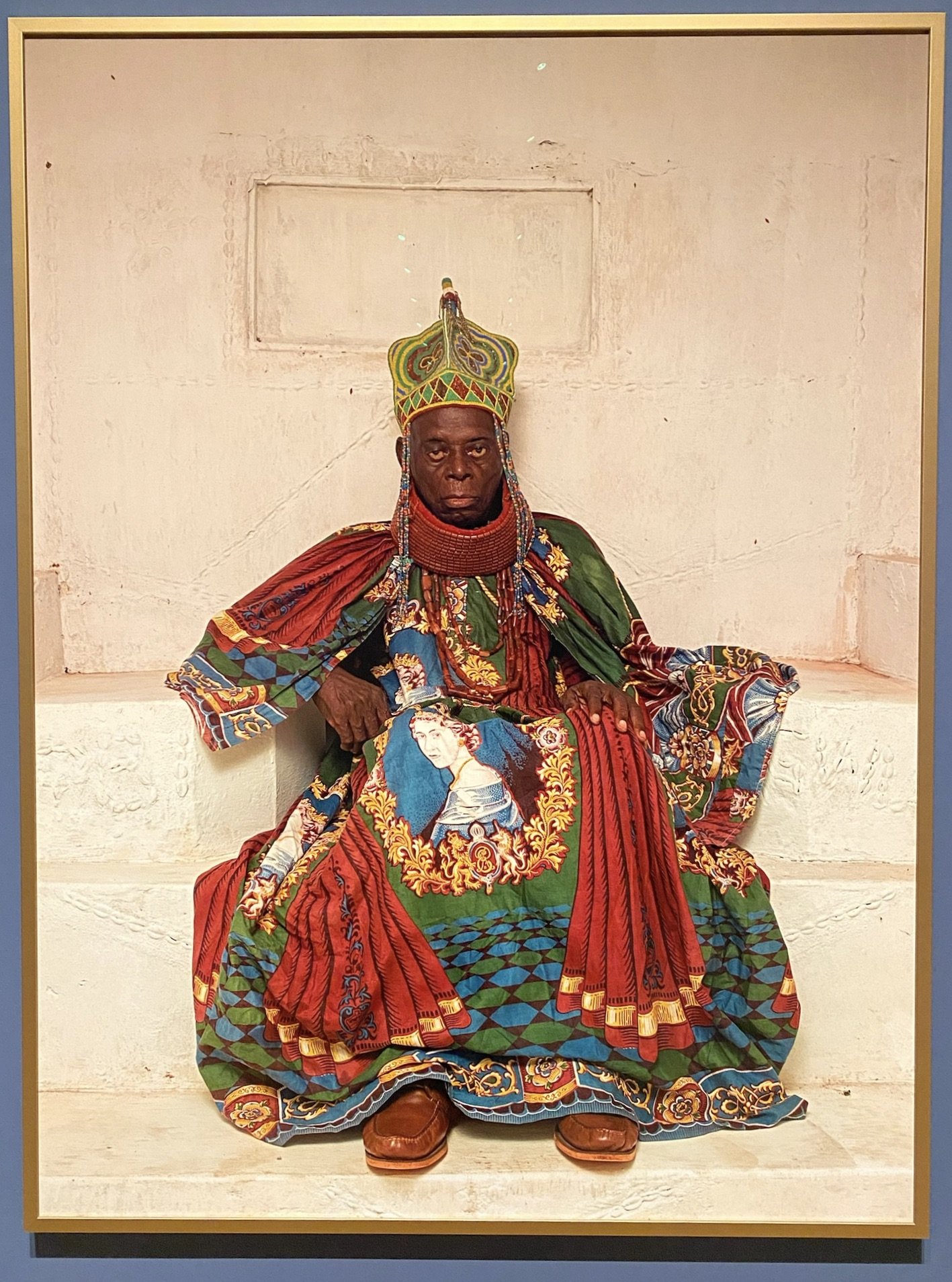

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are encouraged to explore the first chapter titled ‘Kings, Queens, and Gods’. Rooted in the histories surrounding sovereignty, ownership, and relations with ancestors, the works represent kings, queens, and chiefs who ruled over the regions’ land before European expansion. Included in this exploration are their erasures from authority and history during the nineteenth-century rise of colonialism, together with a testament to those who have been able to continue their roles within traditional communities.

Featuring portraits of queens and chiefs from the Asante of Ghana and the Yoruba of Nigeria, the photographs highlight the tumultuous history of identity and community erasure. Simultaneously, however, they also acknowledge the perseverance that has permeated the form of traditional chiefs, kingdoms, and identities, which continue to be practised within the regions today.

George Osodi, HRM Agbogidi Obi James Ikechukwu Anyasi II, Obi of Idumuje Unor, 2012. Image: the Author.

The notion of identity continues into the second room but is now seen through a lens focusing more closely on spirituality. Rooted in African spiritual traditions, the photographs here speak to the intersection of African religions and the introduction of Christian missionaries during the colonial period.

Embedded in body, ceremony, and ancestral communications through oral tradition, many of these rituals have been preserved, with communities still practising them to this day. Fani-Kayode’s works of male bodies accessorised with floral headpieces and doting ritualistic tools, such as masks or a knife, are brilliant contemporary takes on traditional ceremonies. Touching on themes of identity, spirituality, sexuality, and ceremony, each of his five photographs features bodies that appear to be mid-ritual. This allows the artist to provide acknowledgment of forgotten customs while at the same time allowing the audience to become silent participants. By doing so, the artist has created a relationship between himself, his subject, and the audience across time and space.

The sparse background of shadows exemplifies this by leading the audience toward the figure. While synonymous with traditional ritual dress, floral headpieces have become popular within Western society, especially in terms of festivals and weddings, both considered ceremonial gestures. In portraying spirituality through a contemporary lens, the artist is able to connect Africa and the West through their different notions of ceremony.

Rotimi Fami-Kayode, Adebiyi, 1989. Image: the Author.

The second chapter of the exhibition is titled ‘Counter Histories’. Here, the exhibition interrogates the use of photographs as an ethnographic tool during the nineteenth century when images of African peoples and landscapes were distributed in magazines and as postcards. While this narrative is most commonly associated with people from Africa being ‘othered’ through the photographic lens, the photographs displayed focus on the everyday use of photography within these communities in Africa.

Predominantly used for documenting family portraits, the works found in this section of the exhibition lean into the belief of changing the narrative from one of ‘othering’ to one of inclusion. Included is the idea of documenting and archiving – the former used as a tool for oppression and the latter as a tool for reconfiguring history. These ideas are explored further in Délio Jasse’s series The Last Chapter: Nampula, 1963 (2016). Compromised of twelve photographs found at a flea market in Portugal, this photographic series depicts a Portuguese family in Nampula, Mozambique, during the 1960s.

Délio Jasse, Detail from The Last Chapter: Nampula, 1963, 2016. Image: the Author.

The blown-up images are imposed with screen-printed visa and passport stamps, signifying the concepts of migration, forced removal, and citizenship. It is well documented that millions of Africans were displaced not only from their homes but their land as well. Shipped away to colonies around the world, many either lost their official identity documents or were simply destroyed, rendering them nameless and without access to the freedom of movement. The visa and passport stamps also reference the difficulties that many African peoples’ face when trying to move around the globe today. For example, in the United Kingdom, out of the fifty-four countries in Africa, only four countries are exempt from requiring an entry visa.

Installation shot of Délio Jasse, The Last Chapter: Nampula, 1963, 2016. Image: the Author.

Included in the process behind the photographs is the artist’s interest in how the area is depicted. Written within the wall text further explaining the proposition behind the work, the artist states; “They are in Africa but there is nothing that indicated the location […] there are also very few Black people. And the few Black people (clearly servants) are all almost hidden […] That is the contract I was talking about how their lives looked (totally European) versus where they were (in Mozambique)”.

The third and final chapter, ‘Imagined Futures’, acts as a reflective conclusion to the possibilities that can arise when looking at history from a different perspective. Achieved through conceptualising the effects of globalisation and climate change on the global south, this chapter ends the exhibition with a message of hope and possibility. Works relating to human interaction with land, the migration of populations into major city centres, and imagining the future of the continent from a geopolical perspective are all major features.

Dawit L. Petros’ The Stranger’s Notebook series (2016) is a testament to the struggles some face as migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers and their treacherous journeys, especially between Africa and Western Europe. In the series, figures hold up a mirror reflecting a city skyline. To reflect the view, their faces are obstructed, rendering their identity unknown. With the viewer only able to see the area in which the figure is placed, the artist speaks to the unwelcoming nature that many of these migrants’ faces when wanting to enter a new country.

Dawit L. Petros, Untitled (Epilogue II), Catania, Italy, 2016. Image: the Author.

Fabrice Monteiro’s The Prophecy series (2013-15) brings viewers’ attention to the effects of climate change. As figures emerge from heaps of rubbish dumps, the background features open land. Referring to the consequences of overconsumption, the work acts as a warning about the effects consumption has on the land we inhabit. Yet, the artist simultaneously reminds viewers that climate change is an issue shared by the globe and, therefore, not individualistic, regardless of where one is located.

Fabrice Monteiro, Prophecy I, 2013. Image: the Author.

In its entirety, the exhibition proves to be an outstanding testament towards the acknowledgement and appreciation of African photography. While, at times, the line between rediscovering lost archives of the colonial period and the celebration of Contemporary African photography and photographers is blurred, the exhibition, in sum, provides viewers with a comprehensive, thoroughly researched, and altogether thematic experience in the form of mapping each chapter within a specific period of history. Although not all countries were able to be featured, those selected within the exhibition each have a significant and stimulating characteristic that contributes towards the overarching message presented.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography is on show at Tate Modern until 14 January 2024.

Skylar Whittle

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED