Stella Psarouli in Conversation with Artist & Founder of DAMA Galeriá, Mariana Gómez

Mariana Gómez, a Colombian artist and gallerist based in Bogotá, believes that 21st-century feminist art is diverse and widely encompasses countless complex issues and perspectives that cannot be reduced to a single theme or style.

Utilising different mediums including painting, sculpture, drawing, installation, and embroidery, with each piece, she seeks to generate a conversation around the many things that women tend to hide–including topics that society has ruled inappropriate or that are considered taboo. The artist aims to put secrecy aside and speak freely about the nature of women, exposing the bodies, rituals, customs, stories, fears, and struggles of the female gender in a visual and conceptual way.

Alongside her own practice, having most recently founded DAMA Galería in Bogotá, a gallery that focuses on emerging artists, we caught up with the artist to learn more.

Photo by Sebastian Prieto.

Stella Psarouli: Who or what encouraged you to pursue art? Can you tell us a bit more about your background and how you got to where you are today?

Mariana Gómez: It was never a question for me, I always liked art. As a little girl, I used to paint everywhere and do a lot of crafts in my house. Later, in high school, when everybody was asking [what I was going to study], it felt like there wasn’t any other option for me. I didn’t like anything that wasn’t art. But [it wasn’t an easy decision]. I had to convince everyone around me that it was the right choice for me. So when I graduated high school, I studied art at the Los Andes University in Bogotá, one of the biggest universities in Colombia. I took classes in art history, painting, drawing, sculpture, and visual arts and I also did curatorial projects. That’s how that program works. After taking general classes in all aspects of art, we choose our major, and mine was painting. But when I was doing my thesis project, my idea couldn’t be translated into painting, so I tried sculpture without really knowing anything about the process; I was just experimenting. When I completed my Bachelor’s degree in Painting, I decided to get my Master’s degree in Sculpture and completed it at Pratt Institute.

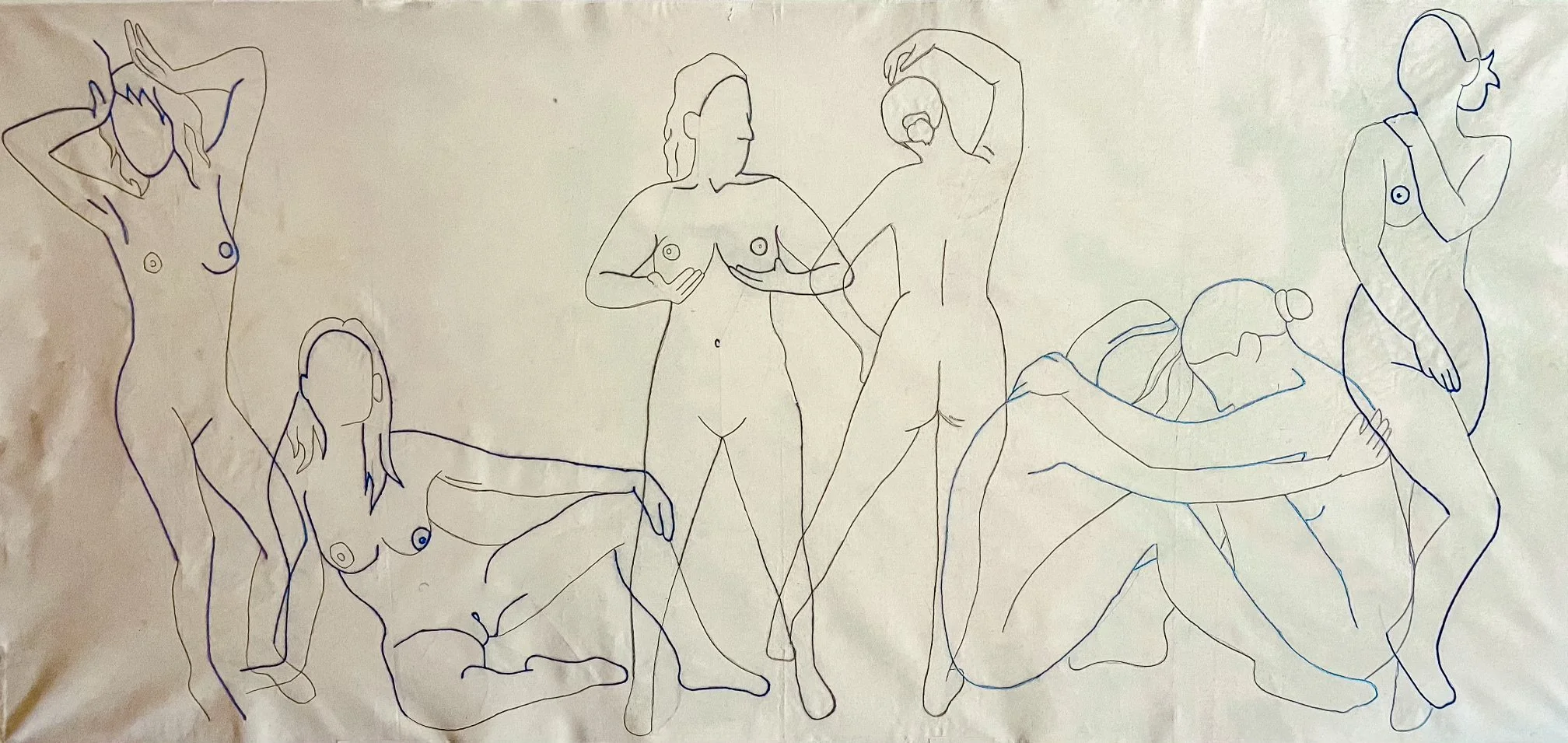

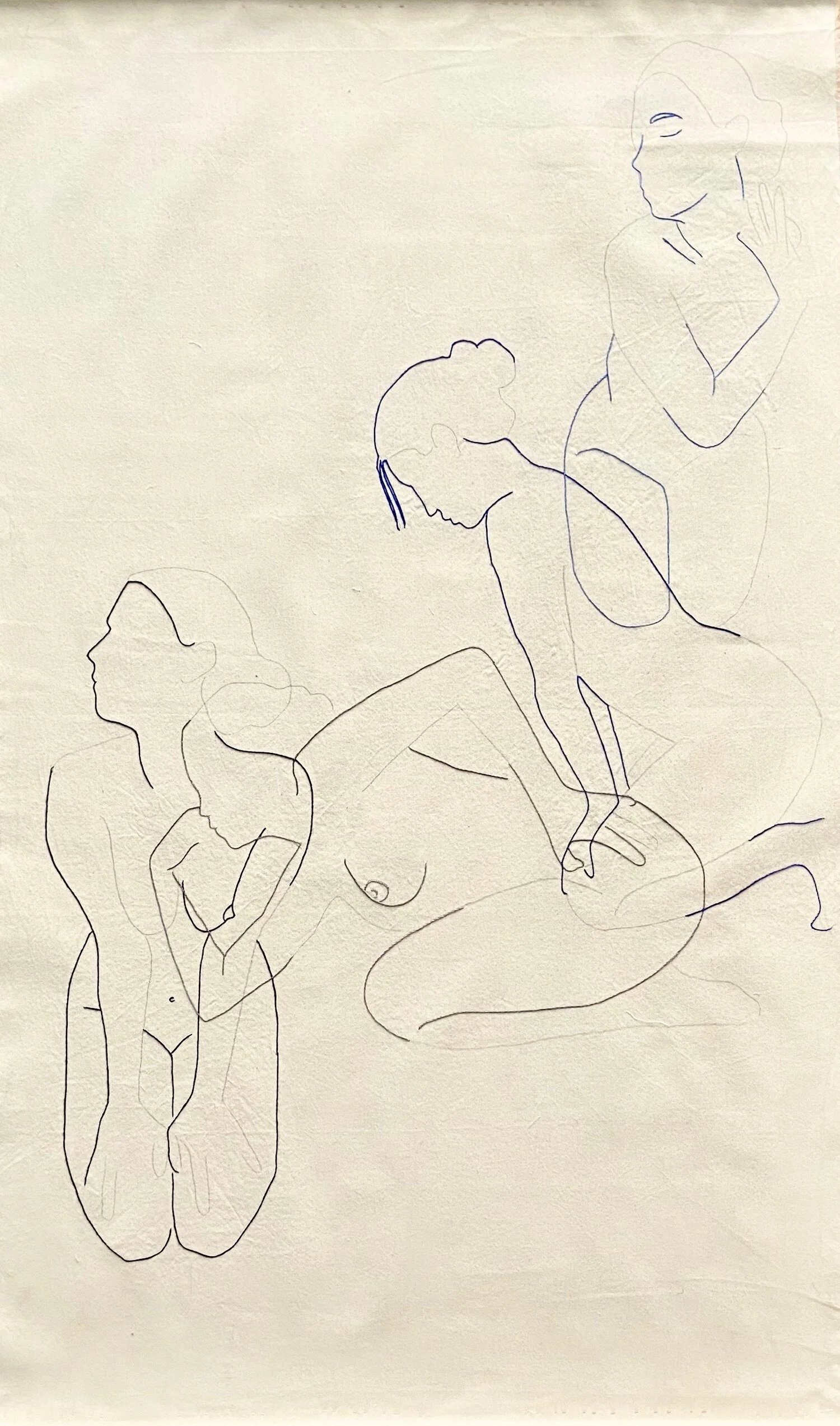

Mariana Gómez, Woman Between Strokes and Stitches series, 2021. Embroidery on canvas and pencil, dimensions variable.

Mariana Gómez, Woman Between Strokes and Stitches series, 2021. Embroidery on canvas and pencil, dimensions variable.

SP: How did studying in New York City influence your practice?

MG: It was very different from what I knew and it entirely changed my way of looking at and practising art. The sculptures I was creating at the time were very different from what I’m doing right now–they were figurative works. In New York, I slowly started investing more in conceptual [works.] I started working a lot on my concept, on what I wanted to communicate to people, and that was a big change for me. Now that I’m in Colombia, I’ve taken a step back from sculpture, but I keep working with a concept regardless of whether it’s a very colourful painting or a very minimal drawing. It’s always the concept behind the piece that’s important–that’s what New York taught me.

Mariana Gómez, Fallopian Tubes and Grandmother’s Desserts series. Installation of intervened hydraulic tiles, dimensions variable.

Mariana Gómez, Fallopian Tubes and Grandmother’s Desserts series. Installation of intervened hydraulic tiles, dimensions variable.

SP: Your work is closely related to feminism, how do you approach that? Is there any specific piece that you’d like to tell us more about?

MG: I like to work by myself, but also with the women in my community, my family, and the women that are really close to me. That’s the way I like to approach my work in feminism, by trying to have conversations and working with my sister, my family, my cousins, my friends, or women that I know. For example, in my paintings or my drawings, I take pictures of these women, naked, which is very intimate work because getting naked in front of someone requires trust in the other person to feel comfortable. That’s part of the work too, namely to create a safe space for the women to be naked, to talk about whatever they want, their bodies, their secrets, their frustrations, or just laugh about whatever they need to. Then, I take the pictures and try to translate them into paintings and/or drawings. For example, once I was with my sister’s family and her mother–we have different mothers–and her aunts and they all got naked and I took a picture of all of them together. That was a very special experience, as they created a feminine union, a union of the family, the bodies, and feeling confident in one another in a very safe space.

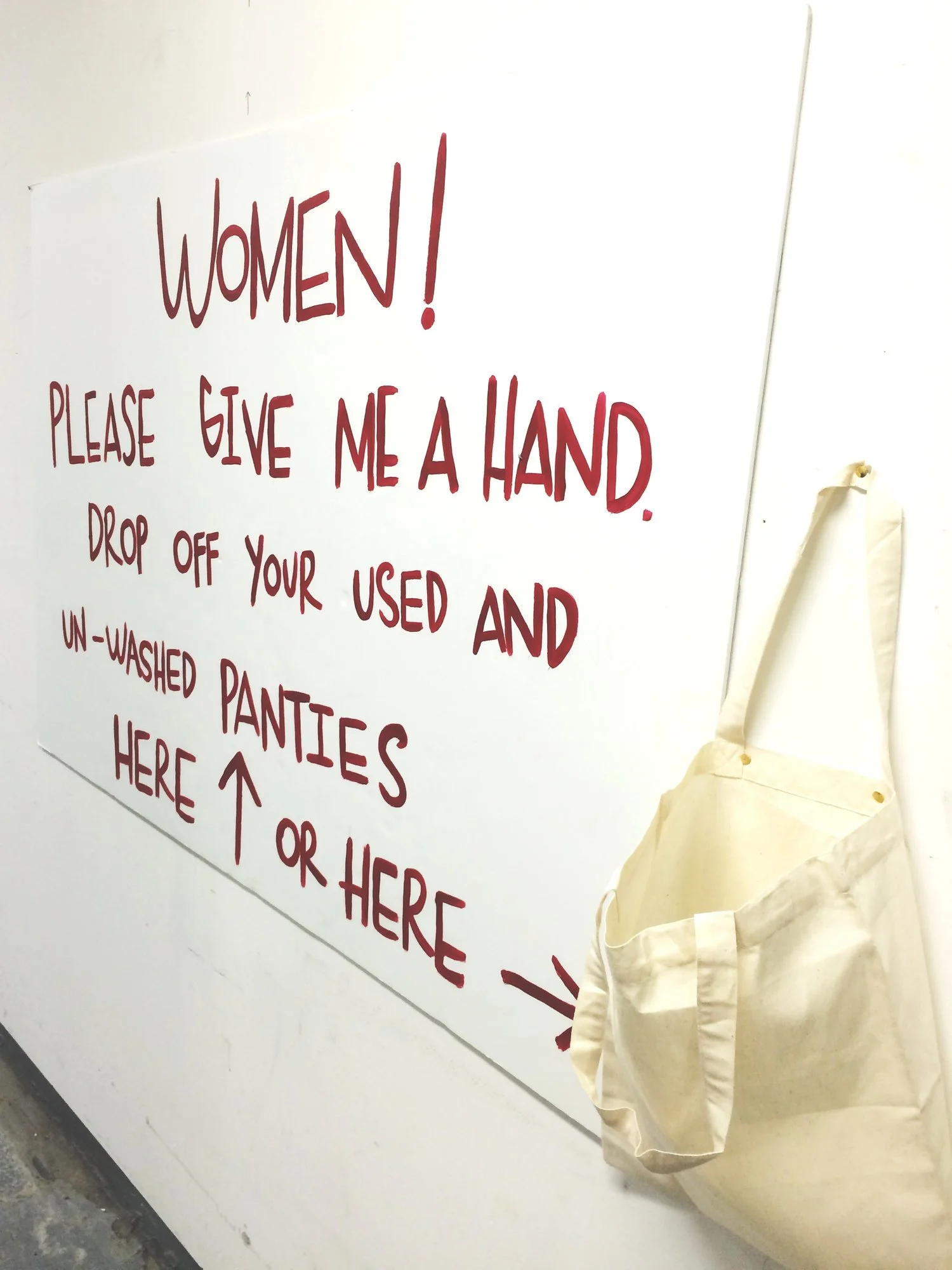

When I was living in New York City, I made this piece for which I gathered a lot of underwear, used and unwashed, from all the women around me. These were by women from different cultures because in New York you find a lot of cultures. That was very interesting because Latin American women, for instance, are freer, but my Asian friends, for example, were more careful, and it was nice to see everybody coming together by giving me their underwear. Some of them just gave it to me, some of them left it in my studio so no one would know, and then at the end, there was this huge piece of union, of all of us together.

SP: You make use of various means of artistic expression in your work, from sculpture and embroidery to painting to drawing, and use a wide range of media. What role does materiality play for you?

MG: I think differently, not about the material but what the concept means to me. What is the material that I need to talk about this concept or to make that idea? Sometimes what you express in a painting, you can not say in a sculpture, or what you can say in a big installation, you can’t put in a painting. So first comes the concept and then I choose the medium that I want to show. For instance, embroideries are something my grandmother used to do and that is a very feminine thing that we don’t use much anymore. It was part of our history as women. We gather together to sew and have all these conversations about sawing and life in general. I wanted to recreate that and that’s why I started embroidery, to recreate that history and the memories I had with my grandmother. I didn’t even know how to sew, I had to learn how to put an idea on that material.

On the other hand, take the installations. I think I choose installations when I have a more powerful concept that I want to do in a very big and very different way. Last year, I made a small installation with pieces of cloth that I have been collecting throughout the years. So again, that piece happened because of a concept that I was thinking about at the time. I wanted to work with these pieces of fabric that my grandmother and older women used to put on tables, or nightstands, to decorate them. That’s what I do. First, I think of what I want to say and then I figure out what is the best way to say it, with painting, embroidery, a sculpture, or an installation.

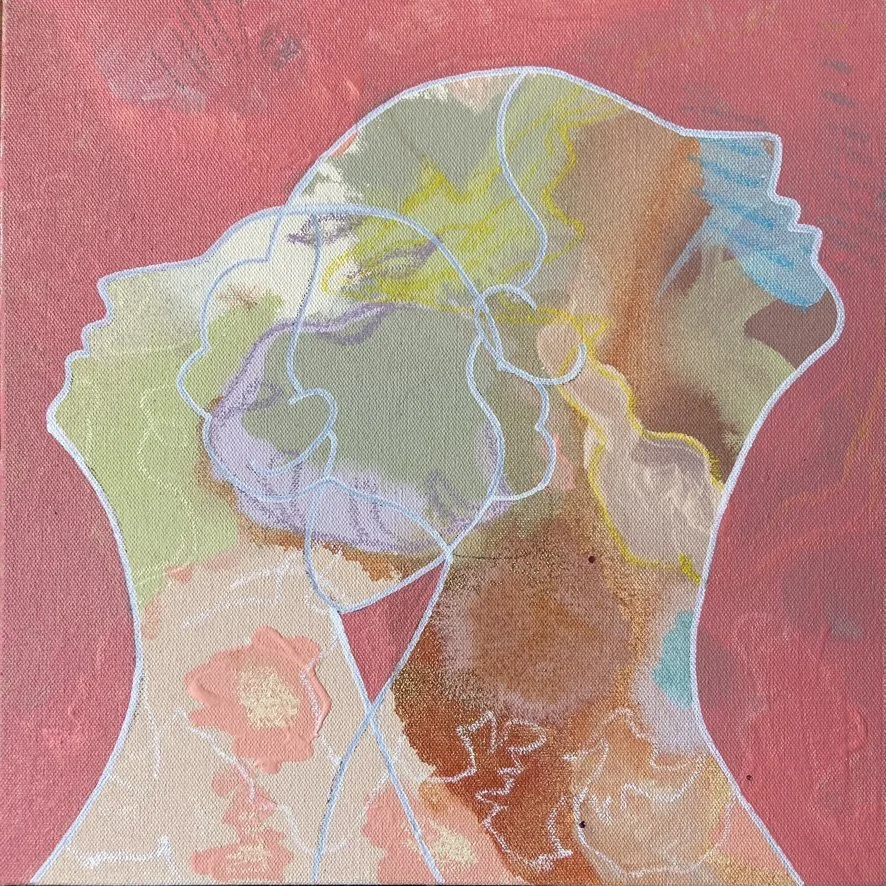

Mariana Gómez, Intimate Abstractions series, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, dimensions variable.

SP: What are you working on now?

MG: Right now I’m focusing on painting and embroidery drawings. In October, I have a show that I’m participating in that is taking place in London. I’m working with embroidery for that show, but with a lot of experimentation involved as I want to take the embroidery drawing a step further. I always do painting at the same time, but right now I’m using embroidery for the experimental and conceptual part of my practice.

I went to Mexico recently and found this cloth with little drawings of Mexican culture. I wanted to add my own drawing to the existing, older ones, and mix the two worlds by creating a conversation between the two cultures. I’m interested in what happens in the female world in different cultures, not only here. For example, they use these pieces of fabric in Mexico, which I was using here in Colombia, but mine was different. In Mexico, they use it in the kitchen to put the tortillas in. Instead my grandmother, for example, was using the exact same thing to decorate the nightstand. But I always liked to work a lot with different cultures. When I was studying at Pratt, I made a piece about the different names that women call menstruation in different cultures. So, in Colombia, for example, we call it ‘the ruler’ or ‘the rule.’ I had a Greek friend and she said they call it the ‘red army.’ In New York, I had friends from many different cultures and I asked everyone, and that’s how I discovered that each culture uses different slang for it. I found that really cool.

SP: You recently founded DAMA Galeriá. Can you tell us more about that venture?

MG: I’ve been selling works by other artists for a long time as a dealer and I thought that the right next step was to open a gallery that would be based more on the artists’ needs. As an artist myself, I would like to have a gallery that wants to show my work, not only the things that are pretty or sellable but also what I’m investigating, what I explore, and what I’m working on at the moment. That’s what I want to create. A safe place for artists to showcase their work, no matter what, so I started DAMA. It opened this year on 12 May in collaboration with the New York-based gallery, See|Me. We had a parallel between New York and Colombia with a show in New York, and after that, having the same one with Colombian artists here. It was a little bit of New York here and a little bit of Colombia there. In that way, we had the big opening of the show but also of the gallery.

I really want to form many alliances and partnerships. I don’t know if it’s very millennial, but I really think that if we work together we can do a lot of things. I know there are some galleries that want to guard their clients and manage everything by themselves because it’s a business. I understand that. But what I want to do is partner up with other galleries, artists, and people, and create a community that we can all be part of. We’re not losing anything. We’re actually gaining by working collectively. I want to create a collaborative ambience.

Mariana Gómez, Men’s Room. Installation in the men's bathroom of the Espacio Continuo Gallery in Bogotá, dimensions variable.

SP: Where do you see yourself in five years–both as an artist and with DAMA?

MG: I was thinking in ten! Sometimes, we see the mega galleries and we think that the competition is very strong and it’s impossible to grow, but we forget that they also started from somewhere. I’m thirty-one now, but when I’m forty in ten years, my gallery and my work will have grown. In your twenties you are just starting, you are experimenting with life, you are working with whatever, doing commissions, or working for free because you want your name to be out there. In your thirties, you’re more established–more focused on what you want. So I see myself in five or ten years with an established gallery but also as a more established artist. I want to start showing my work not only in Colombia, and I really want to start connecting with New York again to start showing more internationally. That’s what I really want and how I see myself as an artist and as a gallerist: to generate conversations, grow, and experiment.

Stella Psarouli

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED