Rhiannon Roberts in Conversation with Multidisciplinary Artist Gala Bell

Gala Bell is a London-based multidisciplinary artist that explores traditional art processes through the transformation of non-traditional materials. Playing on the intersection of the laboratory, the kitchen, and the art studio, she examines the shared practices of the respective ‘maker’s methods’ used within them.

Bell’s early enjoyment of the haptic experience of mixing paint originally prompted her to become a painter before fully branching out into the exploration of additional mediums. Although she is still producing oil paintings on canvas, her work has evolved to include a series of installation and moving image works in an aestheticised display of colour and light with candid, melancholy undertones; her response to the artificiality of the world, or as she puts it, her “reaction to substance and situation.”

MADE IN BED’s 2021-22 Editor-In-Chief Rhiannon Roberts recently visited the artist in her Chiswick studio to discuss the art of deep-fried paintings, the commercial viability of living installations, and what she would say to anyone who argues that contemporary art is not real art.

Gala Bell.

Rhiannon Roberts: To start, can you talk briefly about your background?

Gala Bell: I was born in Zagreb, Croatia but my parents and I are from Bosnia. I came here with my parents when the civil war broke out in Yugoslavia, so I was about three or four. I’ve lived [in London] my whole life. That kind of uprooting of someone and throwing them somewhere else into a completely different culture doesn't immediately strike. I wasn't really immediately aware of it. But I think later on, especially now as an adult, I can see that there's a lot of tension there between understanding your identity and feeling entirely at home with a culture. People don't really think of me as British, even though I've got the accent.

RR: What does London add to your practice?

GB: It adds everything to my practice. Its multiculturalism is really important to me being from somewhere else. In different parts of London, such as my old studio in Harlesden, you have this really incredible Hindu area. You've got the Neasden temple in Wembley. You've got this assortment of Sri Lankan restaurants and bargain stores where you can buy all these different things from India. Or if you go to Brixton, you've got the Caribbean culture. Ladbroke Grove as well, a really big Jamaican Caribbean culture. East London, again, huge variety. Such a melting pot of cultures. One of the things that really got me into creating installations in the first place was this obsession with shopping in these different places or finally uncovering something in the back of a dusty store that I felt was really exotic. When I applied to the RCA, I had such a strange interview. I remember John Strutton, who was interviewing me, said, “It just looks like you've been making [these pieces] in your bedroom.” Now I can understand why. They had a very childish aesthetic. They were made out of plastic and hair gel. They were made with transparent vinyl over big doughnuts filled with gel–sometimes glitter, sometimes Vaseline. Something about being suspended in gel looked really beautiful. They were absolutely hideous but were a result of going to different parts of London and trying to pick up things from different cultures.

Gala Bell, Chariot Race, Funeral Games, 2021. Oil on canvas, 120 x 460 cm.

RR: How has Brexit impacted your practice?

GB: The fact that now we have completely different trade laws and import taxes makes working with Europe actually kind of a bummer for me. Sometimes I get things printed abroad. If I'm selling things abroad as well, it makes it really difficult for clients to import artwork. There's a huge amount of tax that you're meant to pay on that. It’s really difficult and has really limited the people I can work with. I sold a couple of pieces in Spain and in other different parts of Europe and now I feel like that clientele has diminished. Now you have to find smarter ways of getting the work to the venue. Unfortunately, when I did one of the Fry Up shows in Berlin, the work was stuck in customs for two weeks, which is also a complete nightmare. It creates so much bureaucracy and paperwork and really limits the way that people can share across borders.

RR: What was your experience with the lockdowns like? Did they affect what you were making?

GB: They did affect what I was making quite a lot because at one point I really changed direction. It's not something that I've ever put out into the world, but I thought that I’d have to suddenly become a graphic designer. Initially, I was going to start having groups of students come to the studio so I could run a daily business teaching art, which is something that I really enjoy. That wasn't possible during Covid, so I was trying to think of other ways to fund my practice and my life. I was doing Adobe courses, and learning how to use different software like 3D modelling. I spent weeks doing that because I wasn’t able to access the studio for a while, maybe a month and a half or so, so I was constantly sitting on the computer learning all this stuff really trying to change direction. One day I was listening to this talk about typography. You had Serif, and with Modernism came Sans Serif, which basically took off the little flicks to make it all really clean, modern, and efficient. The guy that was talking about that transition was saying that it takes off all this weight. It takes all the weight off the letter and becomes this sleek, efficient thing. When I went back into the studio, it was full of bags of plaster and sugar and loads of paintings that weren’t working and discarded. I was just surrounded by all this matter, and it was really, really heavy.

Gala Bell, A Rare Display of Sapid Detritus, 2018. Deep fried anchor, sugar, glass, glucose, aqua gel, borosilicate flask with Tartrazine powder, jeweller’s specs, steel, tank, 30 x 30 x 35 cm. Photo by Scarlet Lucy Platel.

RR: You have since moved to a smaller studio inside the Hogarth Youth Centre in Chiswick. What has your experience been like with working in a smaller space?

GB: I think it just takes a little bit of getting used to a smaller space, but there is a difference in what work is made. That internal experience of being in a smaller space is very intimate. The other one was very industrial. It makes you make different work. Intimate spaces, I think, are perfect for painting because you can be very insular. You can focus on one piece for twelve hours, and all you need to do is go back and forth, maybe stretch your canvas and move it around a bit. But with sculpture, I need somewhere to be able to spill loads of water on the floor, scrub it, get messy, and produce a lot of dust. I’ve always moved studios every two to three years. I think it’s really important for me because most of the time I make work that reflects the environment in some way. It's very subconscious.

RR: How does site-specificity play into your work? Do you envision how each piece should be displayed?

GB: One of the most important things about producing a piece of work is knowing where it's going to go, how it's going to stand up, and what the viewing experience is going to be. It's different with paintings because, you know, they're going to go on the wall. I think with other things you have to take the environment into account. If the space is not white-walled, you want to create more of an experience of the viewer stumbling upon something or encountering something by themselves. I try and do that when I can, but it's not always possible. Sometimes you're showing in a white space because that's generally what galleries look like. I think the encounter is really important because that's how I make my work in the first place. Coming across something unexpected that you haven't seen before, being mesmerised by the material. The Surrealists talk about that a lot; that in order for something to really feel surreal and uncanny you can’t expect it. I think that’s what creates that surprise and mystery for the viewer; to find something on their own. An example is one of my favourite shows that I’ve ever been to, The Dark Pool by Janet Cardiff and her partner George Bures Miller (1995) at K21 Kunstsammlung NRW in Düsseldorf, Germany. It was the best experience. They recreated a 1950s room with all these collected objects. It felt like you were just going through someone’s house, but everything was staged but in a really careful way, so you feel like you’ve just found it yourself. They had two enormous gramophones where you sit in the middle of them, and you're suddenly enveloped by a conversation. It was very dark as well, so it had that kind of intimacy.

RR: What’s your level of involvement when working with curators?

GB: I think when you're working with a curator, there's always quite a lot of involvement in physically trying to just deliver the show. So quite often, it really depends on the curator. The last curator I worked with had a very clear vision of what she wanted. She made all the decisions about which walls were going to be painted what colour, what was going to go where, and then you just have to slot into that. But they're always very open to suggestions about what you want to do and how you want to do something, so I think you're always going to be very involved. Some people will just let you be free and there's a collaborative effort in making the show happen. I have a friend, Erin Hughes, who runs Cypher Billboard, and she is honestly a wonder woman when it comes to this because she's very organised but she's also very free and doesn't stress out at all. She’ll just let you experiment in a space so that you can do what you want the work to do rather than imposing her own view. When you get to work with people like that, it's great. She’s also an artist herself, so a lot of the time, I think when artists put on shows together, you get some really special stuff.

Gala Bell, The Hidden 66 series, 2018. Sugar, pigment, sweets, dimensions variable.

RR: I find that your work lends itself to a natural curatorial progression when grouped and displayed. Each individual piece is strong individually, but it all connects seamlessly.

GB: Honestly, it's incredible to hear you say that, because that's one of my biggest struggles, actually. That is probably the thing that I'm fighting every day. I can get groups of things to be cohesive because you just instinctively know that certain materials work together. Especially if it's sculptural, you can understand it. But with painting, it carries that burden of the image. It's much less sensorial to me than sculpture is, and they're so different. They're actually almost like two opposing streams of, not history, I don't know how to explain it…

RR: Like two opposing streams of consciousness.

GB: Exactly! It feels like two different people but inside the same person. It’s a difficult thing to want to keep doing that, but it's something I have been aware of for a long time because I genuinely believe that this is how I’m meant to work. Most artists only really find themselves when they're about fifty years old, so I understand that there’s a long future ahead of me. It doesn't matter if I'm literally just eating rice every day, I'm still going to be doing it. I know that gallerists always want something that just makes sense together in space, and I'm not always sure. I'm not always able to display everything in the studio at the same time. I'm always separating things out from each other and flitting from one thing to the next, but it makes sense in my head. Part of that is because art history is so huge, particularly now because I'm looking at the Baroque movement. Erwin Panofsky said, “Every time has its Classical and it's Baroque.” It's sort of like fighting against tradition and the thing that came before. On one hand, I love the craft and there's such beauty in making, but on the other hand, I just want to disrupt everything that already exists–and one of those things is not being entirely cohesive. It's cohesive for me as a person, but maybe not for a commercial space.

Gala Bell, Dendera. Oil on canvas, 65 x 65 cm.

Gala Bell, Anatomy of the Ear or Spiral of the Solar Plexus. Oil on canvas, 150 x 180 cm.

Gala Bell, A Work for Walter Gropius. Oil on canvas, 150 x 180 cm.

RR: Consumerism and consumption are two recurrent themes in your work. Is that more of a side effect of the materials or are you commenting more broadly on these issues?

GB: Consumption is a really big one because initially, I was really interested in the idea of mainly bodily consumption and that insatiable greed to consume physically, like food or sex, but that kind of manifests itself again in all the materials that we just throw away. That's a really big problem for me, especially with what I have witnessed in any tourist destination. Ads and billboards, trash being thrown into the sea. Those are some of the reasons that I started using consumer products, the language of those materials was everywhere and it was oppressive, but when I started using them, it just made me consume even more to obtain the material. It could go the opposite way and you could be making very ephemeral art out of ash or natural materials, which would be seen as more environmentally ethical, but mass manufactured materials are the vernacular of the city.

RR: Overall, your work, as you put it, is “a reaction to substance and situation.” Is that still your overarching thread?

GB: I think it is. I've actually tried to spend time in the past trying to iron it out, which is maybe not the whole point of the practice, but all of it is about that experience of materials. Even though painting has its own place in a hierarchy, and it seems very neat, compact, and something that's quite easily put out into the world, you still have this mess of materials that you need in order to create it. It's not a clean process. At one point Samara Scott said, “I'm just a dumb animal who likes shiny things.” I totally understood where she was coming from. You can conceptualise it all you want, but it’s just instinct really, isn't it? That, to me, is much stronger than trying to stick ideas on top of a piece of work. It really has to come from underneath to erupt out of something.

RR: In your early paintings you aimed to create the effect of light, a goal which later crossed into your installation works. Do you begin with a colour palette in mind? What role does colour play in your work overall?

GB: It plays a huge role in the work. Sometimes I think, especially for painting, that it’s the guiding factor. I focus a lot on how I mix the paint. I was getting quite lost with it at one point, and I literally had to put down every single colour so that I knew how it was mixed. At the end of a painting, having a two-page spread where you’ve got swatches that you've made really helps to keep it organised because what I realised was happening was that there was no clarity of palette. Now I'm very, very clear on exactly how I mix the paint. I’ll use maybe twenty brushes in one session because I don't want to mix them up, or I have brushes that are only there to blend certain edges because otherwise, it can become a total mess. Initially, it's always a mess because I don't have a blueprint that I work from. Everything is just peripheral vision and guided by intuition. I understand that it's maybe quite a retro way of painting, having a blank canvas and going for it, but after you push a painting to its absolute maximum, maybe you’ve worked on it for about a month and you've got all those mistakes and terrible things that happen with the imagery underneath, then something happens. It gets its own style.

RR: You previously described your work as transitional and “a changeover to something else,” and I noticed that you often use ingredients that are in phase two of their lives. You’re using refined sugar; not sugar cane, for example. Is there a reason for that?

GB: That's a really interesting question. With the sugar cane and the sugar, first of all, maybe with the cane specifically, it's really about accessibility and being able to acquire it. I think maybe the fact that I wanted it to be something that was in my immediate environment was what was important. Because for me to be working with sugar cane, for example, I'm so removed from that plant in my everyday experience that it's not something that I'd be able to see and ruminate over and have a feeling towards. And I think that's why. Because for me, it's not like the concept isn't king, it's really much more about emotion and intuition, gut reactions to something. That's what makes me want to make the work. It's the gut reaction, not the thinking about it.

Gala Bell, Sir Henry Tate, 2019. Sugar, mild steel. Commissioned by BBC One Tribe in partnership with Tate & Lyle. Installation of sculpture under the effect of Triboluminescence, an optical phenomenon in which light is generated through breaking chemical bonds in a material when crushed.

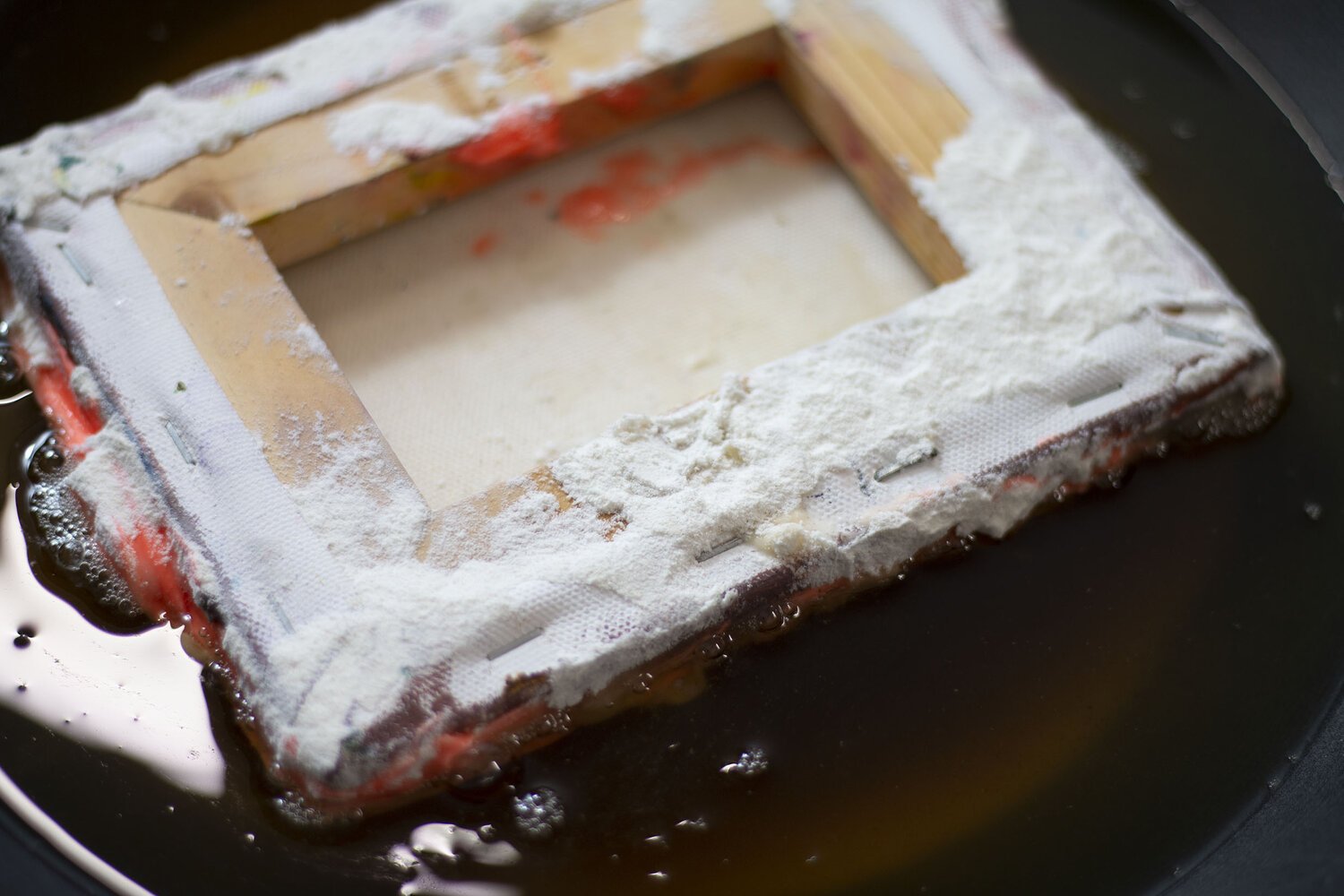

RR: Your work is often in a state of decay. Can you talk about the commercial viability of these pieces? Can somebody purchase Fry Up?

GB: That’s something that I think about a lot actually. With Fry Up, luckily the sugar and oil both last almost forever. Even if I don't put the painting in oil, it never rots. I know with the oil it's because there's no oxygen that can actually get to it. So technically, because there's no oxygen, bacteria can’t grow. With the sugar [in The Hidden 66] as well. Basically, nothing can harm it. It’s rock hard forever. The only thing that can affect sugar is moisture. A chemist once told me that if I put a desiccant underneath the sculpture, it would take the moisture before the actual sculpture does, so apparently, that’s also a way of preserving them. I actually did exhibit some big ones at a gallery for London Design Festival. They were selling them as furniture, so I polished and glazed them so that no moisture could get in. Ideally, they do need about two months to properly stop oozing, and it was a bit short notice, so they were slowly peeing themselves in the gallery. This is what made me realise that they weren’t destined for commodities and definitely needed to be part of a living installation.

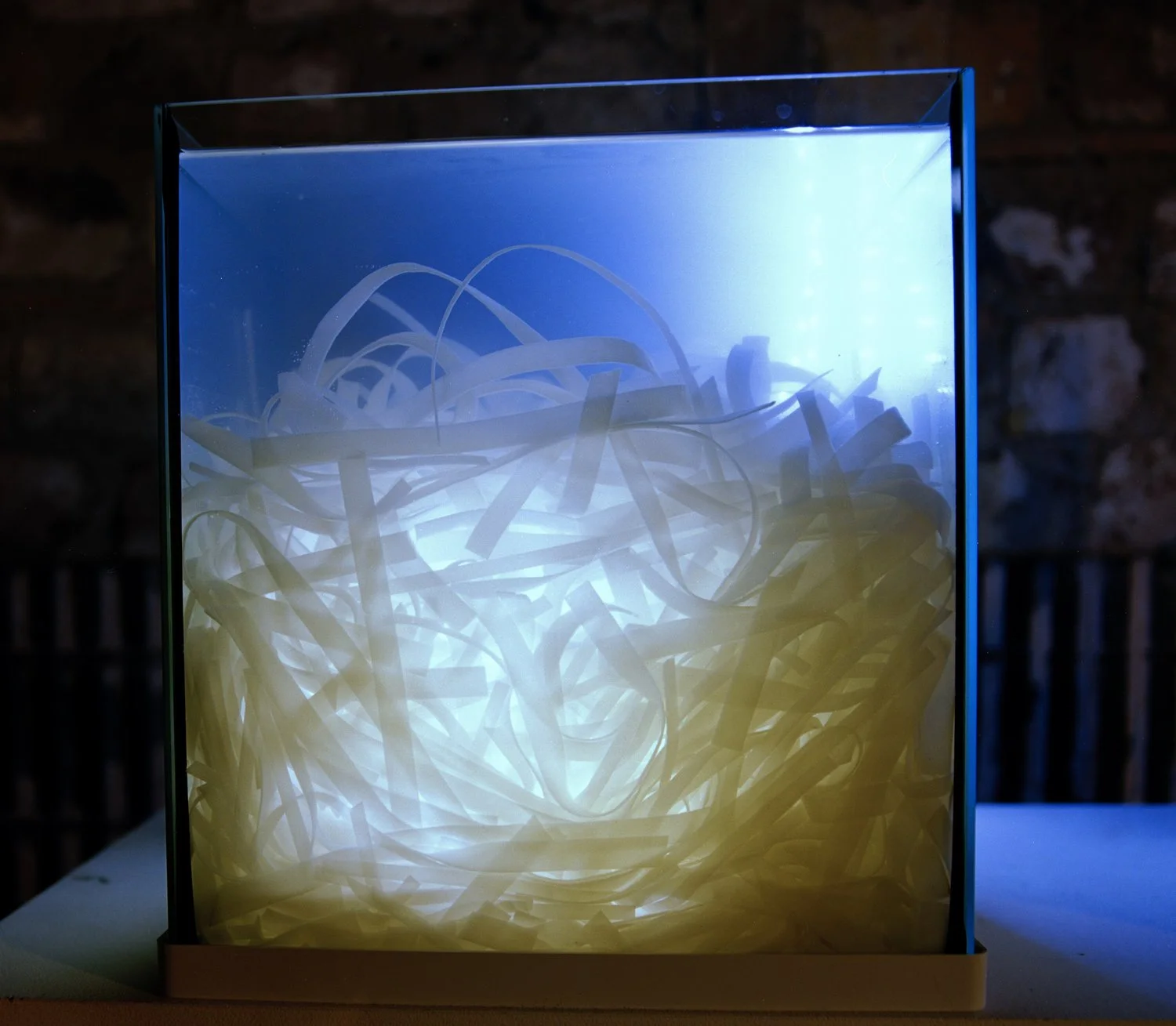

Gala Bell, Aquarium series, 2018. Dimensions variable.

RR: Could you talk about the process of naming your work?

GB: Quite often I think names are one of the most difficult things because, first of all, you want to think about how much you’re directing the viewer to understand what it's about. With Blau, I know why I named it that and find it weirdly cringy, but I'll tell you anyway. When I was painting it, I had a studio in Berlin at that time and was constantly going out dancing. I had a really nice balance of working in the studio till eleven or midnight and still going out and having a really great time, so it was named after a place called Kater Blau that I used to go to. That painting for me was a lot about the motion and movement of gestures that you can create when you're making work. It was very gestural. It all really started just by smearing a lot of different motions of paint. And because it's a very long painting, in the studio, it was like you were dancing over it. With Fry Up, I felt like I needed to call it that because most of the time when I displayed that work before I gave it a title, people didn't know what it was. People didn't know it was tempura, so I wanted people to understand what they were looking at. I felt like that would make it more accessible. I think I know when a work is finished if I can give it a title. If I give it a rushed title, it means that I don't know exactly what's happening in that piece of work, but if I have titled it, that means I fully understand it.

RR: Your practice is so well-informed by art history. Is there a certain contribution you hope to make to the art history canon?

GB: One of the reasons it's so hard to answer that, for me particularly, is because I feel like you have this traditional thing happening with the classicism of the traditional painting and then this other thing which is trying to defy it with these sculptural installations and playing around with different materials. They're so opposite. How could two opposite things contribute? Hopefully, somehow something will happen. You can only hope that the two can mishmash and give birth to one thing, but it might never happen. It might be a case of accepting that there shouldn't ever really be just one kind of contribution. It’s not because I don't want to be condensed. I think it's just because I don't think that's the real way. I feel like that's something that historians have done, and I totally get it. They're just trying to make sense of it, but I think a lot of young artists think that they need to create a certain style too early on and that doesn't really give them an opportunity to grow.

Gala Bell, Supernatural Infatuation, 2018. Noodles, water, led lights, tank, 30 x 30 x 30 cm. Photo by Scarlet Lucy Platel.

RR: Is teaching art something you want to continue doing in tandem with your practice? Do you foresee it becoming a bigger part of your life?

GB: I really do want it to become a bigger thing in my life. I've had some really interesting students. I didn't enjoy working out of a school quite as much. Something about it just makes you want to be rebellious. I don't like someone telling me how to teach art.

RR: It’s such a cerebral thing, isn’t it?

GB: Exactly. I feel that there could be better ways of teaching and that's something that I need to explore and practice myself. But now I feel like I'm able to do that just by spending time one-on-one with someone and thinking about the best way to actually introduce them to making something. How do you get them to suddenly break free from their restraints? For so many years, at least ten probably, when I first started making stuff and understanding the curriculum at school, it was really traditional. I think I’ve been able to break something in my mind only in the last five years which allowed me to have a much more sensory, intuitive approach to making something. Whereas before I was using intuition, but I always felt like it needed to have something stuck on top of it. Now it really isn't that. I have full confidence in following my nose. Watching a kid draw so wrongly and inaccurately, it’s just so great.

Gala Bell, Sol. Oil on canvas, 200 x 310 cm. Private Collection, United Kingdom.

RR: What do you say to the people who argue that contemporary art is not real art?

GB: I think that's really dangerous because you're just burying yourself. You’re stopping consciousness from developing. The whole reason that we have contemporary art in the first place is that people were trying to push ideas and form a new way of thinking about the world. You can't put a stop to that. There was a time when my teachers were so traditional that every time I went to galleries, there was just this common feeling of, “Oh, there's a crisis in art. Art doesn't know where it's going.” No! There was never a crisis. This was all very mature, well thought through history.

Gala Bell, ‘Tiktaalik,’ 2018. Film, 01:31.

RR: What are you currently working on?

GB: In July, we started a social project here at the centre with the local youth group and a group from West London Welcome arriving later in September; it’s a mural project made by painting ceramic tiles based on maps. It looks at physical topography and the texture of land, as well as diagrams of maps to try and rethink the map structure. These kids are all from different parts of the world, some fleeing conflict or much graver injustice, and some of them are from the local area. But again, because there are so many different cultures involved, a lot of it is about finding your place on the map and helping to shift those borders. Claire Bishop stresses the importance of these social projects being very open and very free-flowing. It's about the interaction with the people, allowing them to actually create the work, giving them a chance to make the work, and not having this really austere authorship over what you're making. Currently, the ceramic tiles are four weeks in; 600 have been completed with 400 to go! The process has been so enjoyable and very moving. I’ve been running my own classroom with children from all different backgrounds coming in each day, and there have been some really poignant moments in that classroom. One thing I’ve learned is that if kids are trusted, they’ll do an impeccable job because they are so keen to do right. When someone does something of their own free will, they are more generous, genuine, and fulfilled. This pedagogical approach really works for me as I can witness the impact, as opposed to hanging an artwork in a space and never really knowing what the audience thinks. The reaction is essential!

Gala Bell, Blau, 2015. Oil on canvas, 180 x 350 cm. Private Collection, United Kingdom.

RR: What’s up next for you?

GB: I’ve been planting a few seeds but am not sure which ones will yield. I have quite a few things on the back burner, all meowing for my attention! After this ceramics project is finished, I’ll prioritise my silk designs. I have ready samples of silk kimonos and a shirt I’ve made with a new and improved pattern cut that are waiting to be exported to a manufacturer. It’s been tricky outsourcing and the design still needs some attention, so I plan to keep making samples until I’m happy with the product. Samples will be unique one-offs so stay tuned as they will also be for sale. Depending on how they develop, a Kickstarter campaign may be needed to fully realise the work. In the studio, I’ve been doing a series of paintings using powder pigments and sugar which have been really interesting to me recently. I’ve developed a proposal for an exhibition based on these, so I hope to exhibit them at some point at the end of this year.

Gala Bell.

Thanks to Gala Bell on behalf of MADE IN BED.

All images courtesy of the artist.

Rhiannon Roberts

Editor-In-Chief, MADE IN BED