Nicole John in Conversation with Maro Gorky

Stepping into the world of Maro Gorky’s art feels like entering a landscape both deeply personal and profoundly universal. Known for her evocative use of colour and an intuitive grasp of form, Gorky’s paintings bridge the physical and emotional, mapping memory, geography, and time onto the canvas. In this conversation, she reflects on a life shaped by art—one that began before she could read—offering insight into the creative instincts, traditions, and influences that continue to shape her work.

Maro Gorky in her studio in Tuscany. Photo Courtesy: Stefan Giffthaler.

Nicole John: How has growing up amongst legendary artists shaped your artistic identity?

Maro Gorky: Well, my father didn't want me to go to school at all. I only learned to read when I was eight, and we travelled—after my father killed himself when I was five—around Europe with my mother and her new husband. So, we travelled, and so we didn't go to school, but I did learn to read when someone called Peter Chermayeff taught me on Cape Cod. Peter Chermayeff was the younger brother of Ivan Chermayeff, who did that famous Red 9 sculpture in New York on 57th Street, and his father was Serge Chermayeff, a great architect who was also a friend of my father's, actually.

NJ: So, you knew how to hold a paintbrush before you could read?

MG: Oh, I did. You'll see in the film that accompanies this exhibition that there’s a photograph of me painting at age three with an easel and a stretched canvas. I still remember my father teaching me how to wash my brushes after a painting session, so every time I wash my brushes, I think of my father. I did abstract paintings under his teachings, which are much better than what I do now. Then, after his passing, my stepfather came along. He was from a grand Boston family who came over on the Mayflower. Luckily, he put me and my sister into school, so we had a more conventional upbringing. But initially, my father didn't want me to go to school—he just wanted me to paint.

NJ: You've mentioned your landscapes act as a “visual echo” of your inner thoughts. Can you tell me more about that?

MG: They're actually also maps. And [Saturnia Seen from Above], I mean, it's a map of Saturnia, a famous spa. It's the volcano, the core of the volcano, and all the fields going down, and the hills around, and then the famous Sulphur River, starting up top, that sort of spoon-like thing, that's where it starts. And then it goes down to public waterfalls, and then it goes down to the river, all the way down, and the skyline is the sea. I used to go to the spa and have mud baths with my Italian girlfriends and spend ten days trying to get thin, which we've given up nowadays… It also looks, of course, like a flower. I believe in analogy, so the volcano looks like a flower from the petals of the hills, you see. The brown petals of the earth are very red there because of the iron in the volcanic sulphurous ground—the earth was beautiful dark red, full of minerals. Those are clouds, with the fumes of the sulphur. So, in fact, it's a map of the place where I am, but also mixed up with my feelings about it. So, analogy and geography and understanding cultivation, and what the earth is made out of in that particular spot. I ask, ‘what is the earth?’

Saturnia Seen from Above, 2000. Oil on canvas 120 x 162 cm. Photo Courtesy: Long and Ryle.

NJ: Colour is deeply influential in your work. How do you use colour to evoke specific emotions?

MG: Well, it evokes emotion in myself, the colours. I react to colour very strongly, but in fact, I use it in a topographical way to analyse the different shapes of what I'm looking at and to map it out: to try and analyse and pin down the geometry that's inherent with the negative and positive space, the famous negative and positive space.

To me, it seems very straightforward. I'm very interested in the structure—the physical structure of the landscape is what appeals to me. I just see a segment of a landscape, and I see everything already flat, or maybe in two dimensions, whereas with my husband, who's a sculptor, everything is shaded. He sees around the object and the way the light falls on it, but I already see shapes flattened out from a natural formation. I don't see shadows in that way. Of course, I notice light falling on a landscape, but to me it becomes an abstract shape. Paler light becomes very flattened out and the shape is already formed in my mind, which I want to capture. It's the geometry of the light that interests me as it falls on the landscape or the geometry made by the very geological structure of the earth and the mountains.

NJ: There’s some repetition of different shades of blue in these two works [Spring Vines and Autumn Vines] in front of us. Can you tell me about that?

MG: Well, those are our vineyards and two views of it—one side in the spring, the other in the autumn. I did the autumnal painting first, then the spring. But there again, it's all an analysis of the various things. The shapes stem some trees, tree trunks, and then the trees as natural posts for the vines to climb on, and then the crooked things there are the old, wild vines. Then you can see everything else: either olive trees, or behind them are these maple trees—they have them everywhere, and they grow grapevines up their trunks, which is so beautiful. Once upon a time, they didn't have money to chop down trees and make straight poles for the vines to grow on, so they planted all these acer campestris. It’s much prettier but doesn’t happen so much these days. You see that in Roman paintings in Pompeii, you see the vines growing between trees, like garlands. It’s so poetic.

Autumn Vines, 2025. Oil on canvas 190 x 250 cm. Photo Courtesy: Long and Ryle.

Spring Vines, 2025. Oil on canvas 190 x 250 cm. Photo Courtesy: Long and Ryle.

NJ: The exhibition title, The Thread of Colour, is particularly evocative. What does the "thread" signify to you?

When I use colour, like in that landscape there [Tornano Winter], you can see it very well. You can walk along that red line, walk through the landscape and then you see the various curves made by a ribbon of red, and you can follow it all the way, so it makes this sort of a paisley shape, which is very meaningful and famous. It's an analogy, and also allows you to walk into the canvas like in Hercules Seghers’s paintings. You can walk up the hills and you can follow the woods that make paths and ribbons in the landscape. It's just to help you walk into the landscape, so that you move your eyes, move your eye along these shapes, any shape, just move along, and that creates an echo in your brain, your eye movements, then there's a corresponding musical feeling in your brain, a bit like a pinball machine.

Tornano Winter, 2007. Oil on canvas 120 x 160 cm. Photo Courtesy: Long and Ryle.

NJ: Could you elaborate on the use of recurring motifs, like peacocks, in your paintings?

MG: Well, we had at one point had 17 peacocks…This very good Australian painter called Jeffrey Smart’s dear friend gave us some of his peacocks—a male and female peacock—and I was very excited. I really took care of them. We were so successful breeding these damn peacocks. They’d walk around and around the house, squawking with their rickety ticky tarky, shitting everywhere. They'd be all over the place and they kept on trying to get into the house so we could never leave a window or door open. They were terrible. I mean for about 30 years we had peacocks and then finally when the last one was eaten by a fox, and I was so happy. Those peacock days are over, but they left an impression on that landscape. We see a lot of peacocks in the artwork too—there are about four or five peacocks everywhere in [Spring Vines] alone.

NJ: Working in both oils and more delicate mediums like egg tempera, how do you choose a medium for each work?

MG: I used to use a lot of egg tempera for doing things on sheets of paper, big or small or whatever. I learned it from this marvellous nun in Paros who did icons. I really admired her way of life and her set-up, and she taught me how to use egg tempera.

I used to use egg tempera a lot, but the trouble with egg tempera is that, inevitably, if they're put on a slightly damp wall or something goes wrong, they start to grow mushrooms. Again, like peacocks, it was a very romantic idea to do egg tempera— ‘how marvellous, how primitive, it’s what cavemen did, it's what people have been doing for centuries, very magical’—however, they do bloom mushrooms, so now I use powder paints and PVA. It's not as lustrous, and it hasn't got the gloss of the egg yolk, but at least it doesn't grow any mushrooms.

NJ: Could you describe your vision for the layout and sequencing of the exhibitions?

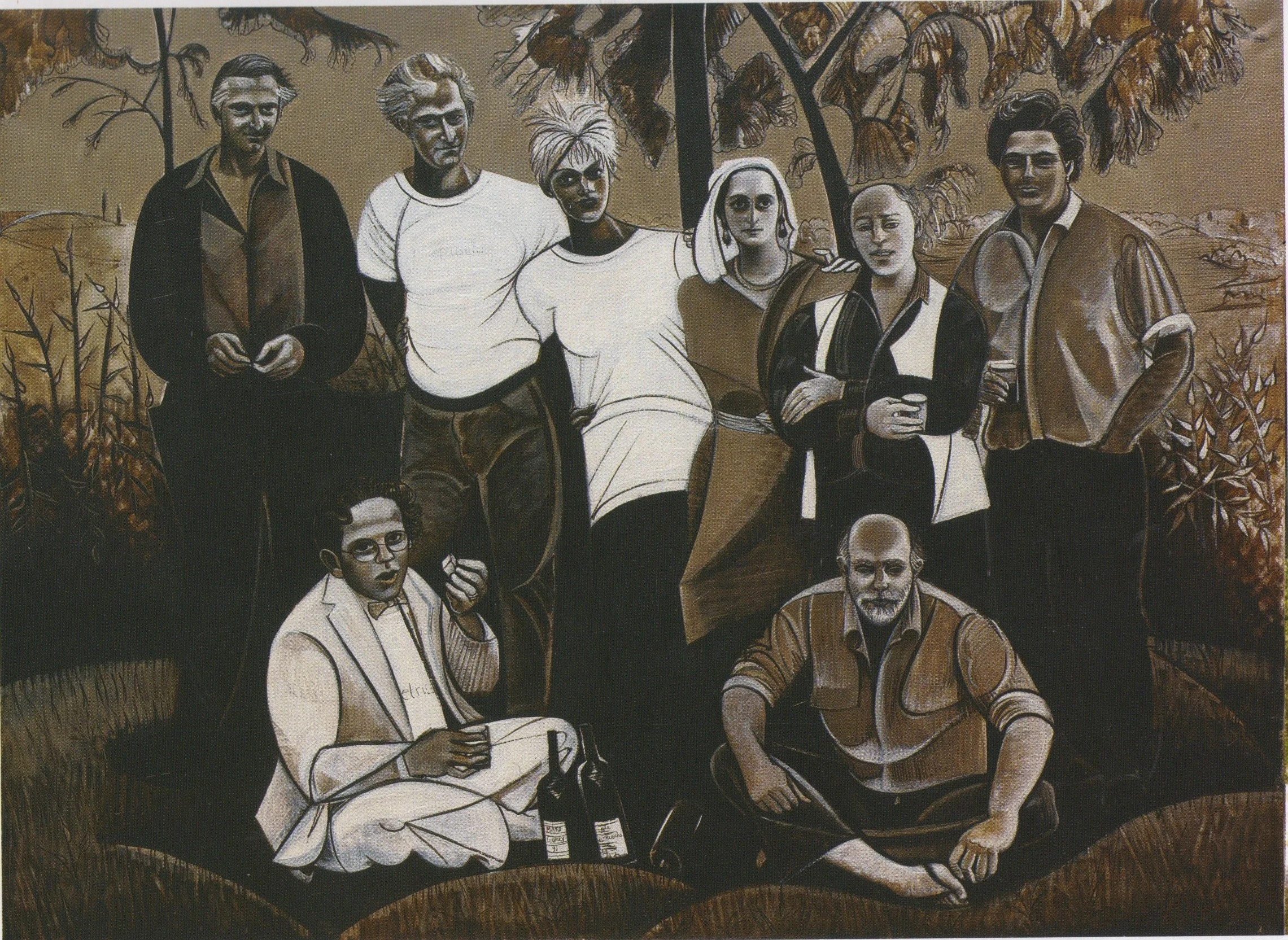

MG: Well, we have these really big works. They had to be hung by themselves. And then there's that big painting over there [The Etruscans] It's monochrome, so also had to be by itself.

The Etruscans, 1991. Oil on canvas 150 x 200 cm. Photo Courtesy: Long and Ryle.

Then this wall here, it’s quite a complicated little wall because it has an opening that leads to Dominic Beattie’s exhibition, so I had to think about his work and respond to it. Then, the painting of my son-in-law, Valerio [Valerio], on his motorcycle, went very well with the peacock painting, because they had more or less the same feeling and colours.

Valerio, 2003. Oil on canvas 140 x 100 cm. Photo Courtesy: Long and Ryle.

NJ: If you could suggest how visitors might approach your exhibition (either emotionally or intellectually), what would your advice be?

MG: I'm just trying to cheer people up. I'm a very optimistic person. I just want them to feel cheerful and happy and see the beauty of the world and go for a walk in the park—there are some fabulous English parks—just to see the beauty of nature. It’s all about nature.

NJ: As someone who has witnessed substantial changes within the art world, how do you perceive the current state of contemporary art? Where do you see it going?

MG: I have noticed that post-Covid, the whole world has changed, literally and intellectually. I think, in a way, these oil paintings done in the traditional manner are probably closer to human beings in 1920. So much is finished now. Nobody likes rugs anymore. Nobody likes complicated clothes that require a lot of effort to make. We prefer to buy cheap things and change them then throw them away. Everything has changed. AI has come in—AI is really good at doing my paintings. I put ‘Dalí’ and I put my name in and I told it to do a painting of an elephant in Tuscany and out came a weird thing that looked very much like one of my paintings. It’s really good.

NJ: Are there particular themes or ideas you're eager to delve deeper into or explore further in your future work?

MG: I really don't know. I can't tell. That's the whole point—it's such fun! We don't know what the future has. You just think of those Japanese clams that you throw into water, and out comes a huge and glossy thing that was hidden within this tiny little shell.

(Writer’s note: Gorky here refers to ‘Japanese Wonder Shell Water Flowers’. )

As our conversation drew to a close, it became clear that Gorky’s practice is as much about perception as it is about expression. Whether translating the structure of a landscape into vivid abstraction or weaving personal history into layers of pigment, her work is a testament to the way art can preserve, reinterpret, and reimagine the world around us. In revisiting her own paintings, Gorky rediscovers the thoughts, moments, and echoes of the past—an ongoing dialogue between time, memory, and the painted surface.

MADE IN BED extends its warmest thanks to Maro Gorky for her time and participation in this interview. A special thank you also to Sitwell Dearden PR.

The Thread of Colour is showing at the Saatchi Gallery until the 13th of May 2025.

Maps of Feelings is showing at Long and Ryle Gallery until the 12th of May 2025.

Nicole John

Reviews Co-Editor, MADE IN BED