Mairi Alice Dun in Conversation with Jack Otway

Cutting up and repurposing old paintings, and allowing raw canvas to show through dry brushwork, Jack Otway is leaving his old style in ruins in his latest body of work.

Otway has been creating and exhibiting in galleries across London and beyond for the past ten years. His paintings build on work of abstractionists before him, but retain an intensely personal feel. Previously, his work has presented itself as richly colorful textured fabrics with geometric forms, combining illusion and perspective to reel the viewer in, but never leave them quite sure if what they’re seeing is realistic or abstract. In his latest show—a two-person exhibition with painter Zach Zono—he has literally and figuratively torn up works from his inventory.

Otway and I sat down to discuss the work in his latest exhibition, The Longest Time at Hurst Contemporary, his practice, and the concept of ruination.

Studio Portrait of Jack Otway, 2024. Photo Courtesy: Brennan Bucannan.

Mairi Alice Dun: The press release for The Longest Time talks a lot about decaying forms, collapse, a moment in time, and destruction. How much of that was your words?

Jack Otway: The words? None of it. The vibe, the atmosphere relating to ruins, that was my idea. Ruin and ruins.

MAD: Are you interested in academic interpretation?

JO: Absolutely. Or, at least, I’m interested in the paintings being more than what they seem to be. Recently, I’ve been thinking about how paintings can have subjectivity, how they can retain (or lose) traces of labour, and how they can explore ideas of interconnectedness of hybridity. I’m not looking to be prescriptive, though—I make abstract paintings. If I was looking to be prescriptive, I would have just painted the ruins I am referring to, the ruins that my paintings are standing in for: personal ruin, the ruin of relationships, the ruin of bodies of work, things like that. It’s very much inspired by seeing physical ruins on my trip to Jaffna, Sri Lanka. How the ruins contain memories of complex histories. I felt both deeply affected by this experience but also disconnected from it, I was a tourist. So I guess the question I asked myself is, how can painting produce a similar sensation when it comes to my own history?

So, yeah, all the paintings that are in this show depict just one of my paintings, a work that I made in 2022, and the signature and date that was on the back is now sometimes visible but fragmented and made illegible. That timestamps it for me. I was making that painting at a very specific time in my life—when my estranged dad got sectioned, was diagnosed with what we now know is dementia, and we had to put him in a home. From then on, I worked more than ever in the studio. Buried myself in work. So it was important for me to memorialize that, memorialize that time spent. It’s what I did and I’m making sense of that. So you have this academic framework and this exploration of memory and autobiography.

Jack Otway, The Stone Sees Only Downward, 2024, oil and wax on canvas, 100 x 200cm, at Hurst Contemporary. Photo Courtesy: the artist.

MAD: You told me when you were thinking about what you were going to do for this show that you were considering cutting up your old work, and it looks like you then formed the strips, took a picture, and then you painted that?

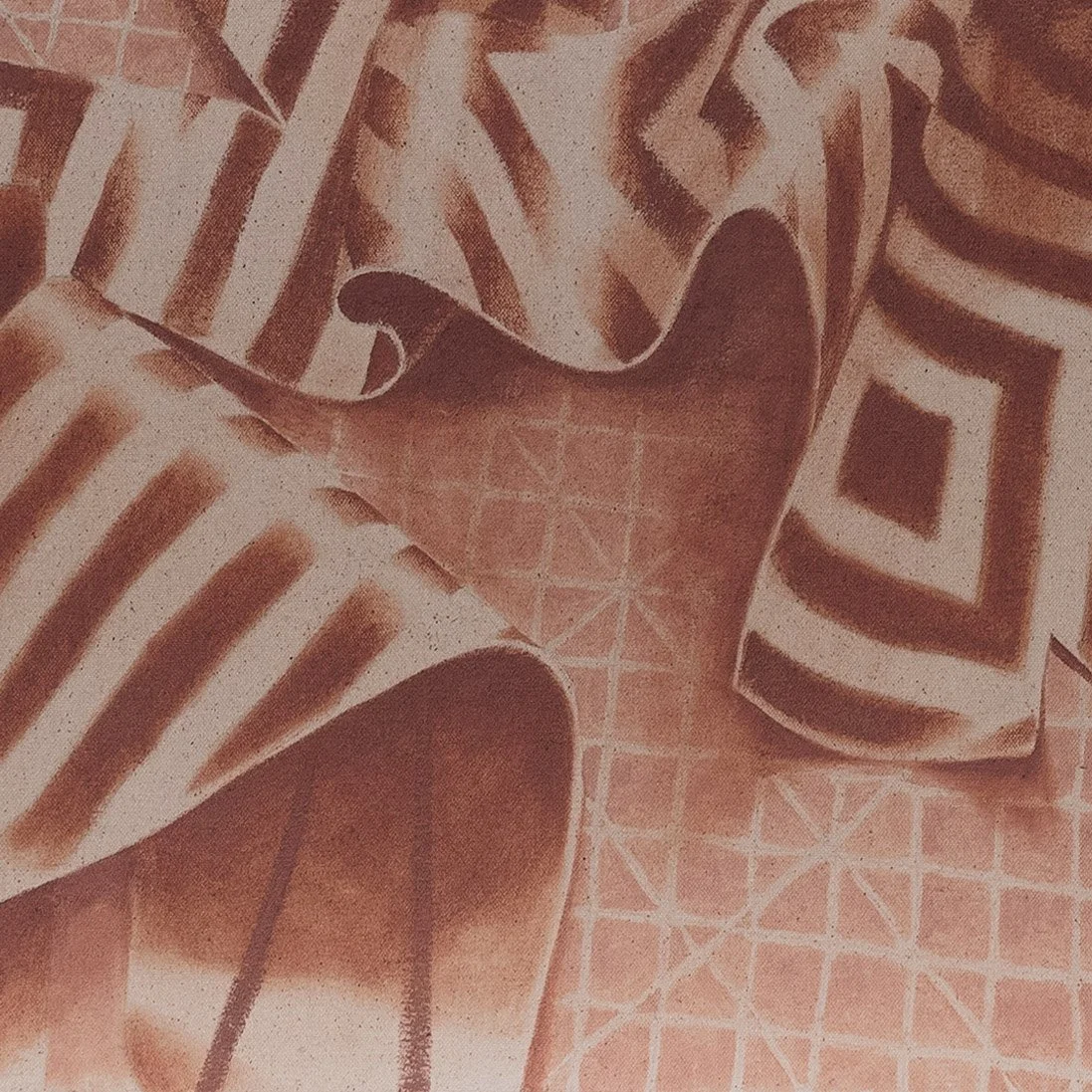

JO: I would throw them and then photograph them where they fell on the cutting mat. I wanted it to feel natural. Then I painted from the phone. It’s quite matter-of-fact. The Stone Sees Only Downward is pretty photorealistic because it was the first one I made with these ideas in mind. I gave it a sepia tone, like an old photograph. I feel like I had to get that glow—that almost filmic glow from the surface, like romanticizing an object from the past. False nostalgia. In hindsight, it's an exercise in drawing and translation, which I don't normally foreground.

MAD: This differs from what I’ve seen you do before. It’s not that smooth, oil paint-look with no visible brushstrokes.

JO: It’s going back to a less-idiosyncratic process—disassembling, assembling, photographing, drawing, painting. I’ve built a toolbox of marks that are only available because of the slick surface I’ve been tinkering with for years. The transparent layering of different abstract forms in past work provided a visual metaphor for interconnectedness and multiplicity that I’m interested in. But essentially I was working with effects and I needed a new strategy to achieve the sensation I was looking for.

Jack Otway, False Doors, 2023, Oil, acrylic, dispersion on polyester, 60 x 85cm. Photo Courtesy: 243 Luz, Margate, and Ollie Harrop.

I never felt comfortable going from A to B, knowing what B was going to be from the start. But I was so stuck on the old surface that I was using, which was non-absorbent. I could just wipe it off at the end of the day. So sometimes I'd have a day, like 16 hours in the studio, and I wouldn't have found anything. That spirit of invention hadn't flowed through me. And it would happen again the next day. Which, when you have shows and deadlines, is not a healthy way of working. Now I have a set process and subject: my archive, my inventory.

MAD: Why come back to drawing, something you say you hate?

JO: It's not that I hate it. It's just that I really conceptually believe that painting, and that act of painting, is a place where you can invent new forms…and I think drawing can hinder that. But of course there are rules you can use, or not use, and there's that tension between searching and looking back and trying to stay present in the studio and in life. I think now I've been looking inward to personal experiences with travels, relationships, bodies of work, things like that, but also to drawing as a tool, in the sense of translating a space onto a surface. I now do most of the inventing off the canvas and translate it with drawing.

For example: okay, I want my cut-up signatures to be in the work. I want this black square to appear in all of the work. I want it to feel sun-bleached, or like an old photograph, or dead, in a way, in terms of the light, or I want the forms to feel like portals or flags, or I want the remnants of signatures to resemble unreadable glyphs or the cutting matt to feel like paving. I can draw all of that. I can plan it, and then I can do it. What has always been the most difficult thing for me is the question of what my subject is. In this series it's personal. It’s about labour, time, structure, fluidity, light, decay.

Jack Otway, Part Buried and Bleached, 2024, oil and wax on canvas, 46 x 117cm. Installation view at Hurst Contemporary. Photo Courtesy: the artist.

MAD: Would you say there's a focus on perspective? Thinking about vanishing points and things of that architectural nature that you're dealing with in these new paintings?

JO: Yeah, it is abstract painting that uses a more traditional concept of space. And then of course they’re painted from photographs so you have this slightly distanced and framed sense of space.

The scale of The Stone Sees Only Downward gives that sensation of architecture, or a relationship between space and the body. But the curls of the old canvas directly reference lemon or orange rinds in Flemish still life paintings—which are stand ins for vitality. So, again, you have this coexistence of different spaces/genres/structures/elements.

Detail of The Stone Sees Only Downward. Photo Courtesy: the artist.

MAD: The Longest Time considers the natural world—reclaiming those spaces humanity has taken over. I can see how you came to that by seeing physical ruins, but can you tell me how that comes across in the work in this show?

JO: The Longest Time is a two person exhibition—Zach’s paintings reference his upbringing in South Africa and the landscape there. So I think that the concept of the natural world and its relation to man-made structures fits loosely with my interest in structure/fluidity and decay in the context of the show. A landscape is always just a landscape for us, right? It depends on where you, the subject, are situated. When we talk about landscape we talk about our field of vision, and the idea of us walking through it, as if we are there. It’s a very human-centric concept. It’s where memory is held, where it occurs. So in that sense there is a link to my interest in spaces/objects that bare the traces of memory.

MAD: Why have you decided to keep the grid of the cutting mat in this series?

JO: In terms of thinking about hard edge abstraction—a friend of mine recently said, ‘you know, you use the grid a lot, and the grid is safe.’ And I don't agree. I don't see it as safe. I see it as a challenge, because you have this rigid structure, that fixedness is violent and clean. So working through that, it's like, okay, well, how do you create structure or use structure and challenge it, break it, evolve it.

Detail of Part Buried and Bleached. Photo Courtesy: the artist.

To oversimplify it: that tension reflects how we live life. There’s structure, but there’s also fluidity and transition. I hope that—through the more personal thrust into that idea—I’ve made some strange paintings that deal more in affect than effect.

Many thanks to the very cool Jack Otway on behalf of MADE IN BED.

To learn more about Jack and his work, follow him on Instagram.

You can find Jack’s work in The Longest Time at Hurst Contemporary in Bloomsbury until 7 January.

Mairi Alice Dun

Editor-In-Chief, MADE IN BED