Emily Crozier in Conversation with Artist, Paul Smith

57th and 3rd, 1986.

A recent surge of interest in the 1980’s East Village, New York City scene has inspired the documentary on artist and AIDS activist, David Wojnarowicz; a show of works by artist and gallerist, Tim Greathouse; and this past weekend saw the highly anticipated opening of Paul Smith’s solo show, The Human Curve, at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York.

Paul Smith has a B.A. summa cum laude from Bowdoin College and an MFA from Brooklyn College. Smith’s works are included in the collections of the New York Stock Exchange, Coca-Cola and The Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh. Smith has received the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors Award, a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant, a Cummington Center for the Arts residency, and a Skowhegan School Governor’s award, among other prizes. He has also taught at Brooklyn & Queens Colleges, CUNY, the Newark School of Art & the New Jersey Center for the Arts.

In this interview, MADE IN BED’s Editor-in-Chief, Emily Crozier, talks to Paul Smith about his artistic practice, his vast professional portfolio in the art world and his memories from days spent in the 80’s East Village scene.

Thunderbird, 1985.

Emily Crozier: The title of your current show, The Human Curve, in part references your use of wide-angled, curvilinear picture planes. Would you please tell us a little more about this component of your artistic practice?

Paul Smith: I started as a painter, making wide panoramas. I wanted to make the panorama vertically wide-angled as well as horizontally, but I realised the perspective was diverging; edges were curving away from me. To reconcile the horizontal and the vertical, I needed to make splits in my composition, similar to flattening out a globe into a map. So then I started to paint on curving, three-dimensional objects I made. While experimenting with this in painting, I made pinhole cameras with curving film planes. I became captivated by seeing perspective directly through pinhole photography.

EC: Can you tell us about your decision to capture your photographs exclusively in black and white?

PS: Pinhole exposures are typically very long exposures. I usually shoot with paper negatives in bright sunlight for three minute-long shots. Initially, I tried coloured film, but after an exposure of a second or longer a colour shift would occur- the film increasingly registered to the red/orange/yellow spectrum. They looked apocalyptic, as if the world were on fire, which was interesting but extreme. So I tended to use black and white paper negatives. I liked to make large negatives, and then contact print the paper negatives. In those pre-digital days, one had much more control in the darkroom with black and white.

Barricade, 1983.

EC: Despite the long exposure needed to capture these photographs, the subjects give the appearance of being captured spontaneously. When taking these images did you stage the scene or was the story told to you by the subjects?

PS: The landscape around my apartment was very dramatic around 1983. The neighbourhood was very torn up. The city had just gone through a fiscal crisis and many landlords had walked away and abandoned their buildings, rather than pay their property taxes. It was a high crime neighbourhood. Some of the abandoned buildings were being used by addicts as galleries to shoot up. My front stoop was a marketplace for selling prescription pills and there was a heroin marketplace a few blocks over. Also, the city was replacing old sewer and water pipelines. so a lot of the streets were completely torn up with construction. My first series was called Struction, about the destruction, construction, and flux. The next year, 1984, I started to pose sexual narratives with friends on the rooftop of my building where we could pose nude in sunlight: which became Bodily Fluid. There was a recent realization then that AIDS was transmitted through bodily fluids. But my construction then also became more fluid in their own body curves—I was trying to capture a sense of the fluidity of actual vision. There was a programme in that sense, but it was fairly exploratory: to what I was seeing around me and my sexual feelings.

Tar Beach, 1985.

EC: Could you tell us more about these influences? As your photographs were taken at the time of the outbreak of AIDS, were these also taken in response to the epidemic?

PS: It was a different era when I graduated from college. I was discovering that I was gay and was slow to come out. There was much less gay life in the media, so I graduated college (I realized later) with ingrained homophobic attitudes. I was in love with a straight boy and wanted to be straight myself, like him. I had a wonderful girlfriend. The city, however, began opening me up to new experiences. This was the same for friends of mine such as Marion S., a photographer who also showed with the Greathouse gallery where I showed, who had filmed The Pier (an abandoned pier where men had sex, and where artists began to make grafitti paintings), and who helped David Wojnarowicz with his photographic work, with the complicated dark room work for his sex series, for example. She was a sexually adventurous woman who was willing to pose in sexual narratives with me. For the homosexual narratives, I actually used a straight friend of mine, Joe, who was very unconcerned about posing very intimately with me. This was all happening when there was no treatment for AIDS.

Dick Head, 1985.

EC: Art dealer, Daniel Cooney, described you as a ‘vital part of the 80s East Village Scene’- can you tell us a bit more about what that scene was like and the network that you formed from it?

PS: When the East Village gallery scene was just starting, I was involved with a squat, a non-profit artist space on Rivington Street where I lived, called ABC No Rio, started by a group of artists called Collaborative Projects. They had done a show in a former massage parlour in Times Square that had gotten a lot of acclaim, as a new generation of artists emerging in the early ‘80s. At ABC No Rio, I did a show of work from Central America about the war going on in Guatemala. Later I put together a group show on election issues before the 1984 Reagan-Mondale election. That led me to a new network of artists.

I curated shows in nightclubs. There were very few commercial galleries that were showing emerging artists at that time. It was difficult to get galleries to even look at your work. Nightclubs provided a dangerous but lively environment for art. At the Kamikaze Club I organised a big group of artists focused around a common theme--homelessness, called All The Comforts of Home. I invited friends who didn't have galleries, to show work there. It was interesting to see the unexpected ways that people would interpret a theme. This was before Facebook and Instagram, so it was a way to interact with other artists.

The gallery scene in the East Village then began to explode, and Tim Greathouse asked to see my work. When I brought work in, we were interrupted by people coming in, and he asked me if I could just leave the work and come back in a few hours. When I came back, he had shown my work to those people, who were curating Neo York at the Santa Barbara University Museum, about the East Village scene. They had asked to include that Struction work in the show, and Tim asked me to join his gallery. While we were talking, David Wojnarowicz walked in and Tim introduced us and showed him my work. I’d loved David’s work at Civilian Warfare gallery, so it was an incredibly exciting day for me.

EC: You have experience in many different disciplines within the art world. How did you come to have such a diverse professional portfolio?

PS: I thought I was going to be a writer before I decided to become an artist. When I moved to New York after college, I started writing about exhibitions for Arts Magazine, which was an interesting magazine, edited without a lot of interference by Richard Martin. He allowed a lot of different voices—Donald Judd, Pincus-Witten, Donald Kuspit. I hoped that writing would help me get to know artists I admired, although, surprisingly, it didn’t really. It helped me think about my own feelings about art and try to formulate my particular vantage point.

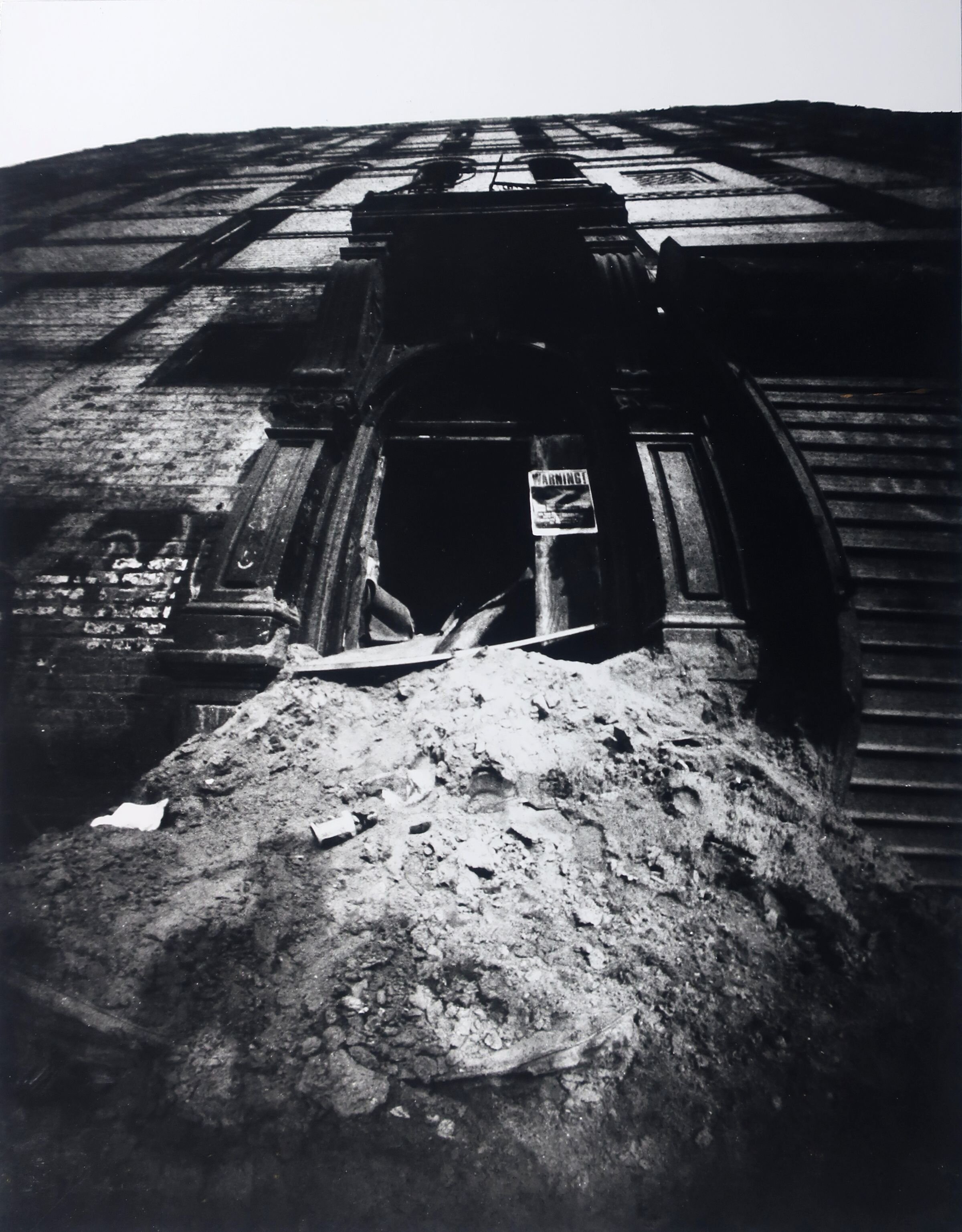

Warning, 1985.

Dig, 1984.

EC: As your show presents works exclusively from 1983-6, at the start of the ruthless gentrification of New York City, do Dig and Warning reference this change happening in the city? Was it noticeable/felt at the time?

PS: They do, though at first, gentrification didn't affect me that much. Even when the East Village became a happening neighbourhood, strangely, below Houston Street where I lived, wasn't much affected. My building, for example, had many Chinese tenants who didn't speak English. Some of them collected empty bottles on the street to deposit for income. I was jealous of my upscale friends who lived in lofts, where the other tenants were artists too. My immediate neighbourhood remained derelict, which I found fascinating, and almost romantic. I liked the anarchy of it. I never felt that threatened in my neighbourhood, until crack [cocaine] came--that made things actually seem dangerous. I began to wonder if I shouldn't romanticise it so much. Only recently did new buildings begin to dominate.

Bather, 1985.

EC: Daniel Cooney described you as an “under the radar artist”. What prompted you to do this exhibition?

PS: When I heard Daniel Cooney was doing a Tim Greathouse show, I approached him. A critic friend had visited my studio around that time and had encouraged me to dig out my early eighties East Village work. He pointed out that the period was having a revival of interest.

EC: Do you have any other exhibitions coming up?

PS: No, [but] I have a lot of work I would like to show. I went from pinhole photography to making similar curving constructions with digital cameras, stitching lots of photographs together, and using Photoshop as a Constructivist tool. And I make paintings. Almost none of that work has been seen.

Paul Smith’s show will be exhibited at Daniel Cooney Fine Art from November 14th-December 19th 2020.

Imagery courtesy of Daniel Cooney.

Emily Crozier

Editor-in-Chief, MADE IN BED