The Totemism of the Absurd: Luisa Me’s Grotesque Aesthetic Between Iconography & Sacredness

With paradoxical irony and colourful expressiveness, the Italian duo Luisa Me creates a universe of deserted beaches, grotesque characters, and industrialised landscapes.

Looking at sacred art and Camus' thoughts, MADE IN BED's Feature Editor Federico Raffa explores the two young artists’ works on a journey through iconography, totemism, and absurdity.

The Italian duo Luisa Me with I’m a Beautiful Flower, 2021.

In 1967 Roland Barthes published a short essay entitled "The Death of The Author", stating with a few simple words, almost from a minimalist point of view, how art is endowed with expressive independence to which every spectator can give his/her personal and unique interpretation. Therefore, the author dies in favour of the work, which will be the one to assert itself, addressing the audience directly. Yet, going against Barthian thought, it could be argued that, in a structuralist perspective such as Art History, artistic language is sometimes based on canonically defined and universally recognised symbolisms. The Italian duo Luisa Me’s works are placed in this communicative context, oscillating between work's free expressiveness and iconography.

In their latest production, the two artists propose a series of grotesque, totemic, colourful, ironic, at times foolish works on canvas and sculptures, united by the sea and the beach theme. Anthropomorphic figures with bright colours and angular, Kafkaesque, mannerist shapes inhabit this bathing universe in which flowery beaches, rough seas and industrialised horizons alternate. In a dreamlike context, vacillating between the paradoxical and the familiar, explicit references to Christian iconography immediately catch the eye. For example, in "I'm a Beautiful Flower" the central figure, positioned precisely in the middle point of the canvas, with its legs crossed and arms outstretched, immediately recalls that of a crucified Christ, symbol par excellence of the Christian religion and central theme of sacred art. As in paintings of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the figure has a characteristic yellowish skin, which, however, in the specific case does not seem to be connected to the symbolism of gold as divine but rather resembles a sick, hepatic body. Moreover, contrary to the classic iconography, in this case, the figure, endowed with only one eye and with a slanting face, almost as a sign of madness, does not seem to feel pain and suffering; instead it smiles, probably aware of its soteriological role.

The Sun Will Hold Your Tongue, 2021.

The clear references to the history of sacred art in an image with eccentric tones and clumsy shapes could appear as a blasphemous, desecrating, ironic as well as a provocative act, at the same time raising a question about the concept of “the sacred”. Deriving from the Latin sacer, the latter etymologically indicates something "other", outside of society. Notoriously understood as something related to the cult of divinity, as opposed to the profane, the sacred has been the subject of different interpretations. The German theologian Rudolf Otto defined the sacred with the adjective he coined, "numinous", indicating precisely the peculiar experience of an inexplicable, alien presence, which inspires terror and at the same time fascinates. The sacred, however, does not correspond to the divine as it does not appear independently but always assumes a qualitative character in relation to any vehicle of connection to the divinity. Sacredness is a condition that can be specific to various things, such as a place, an action, a text, or a person. In these terms, anything capable of fascinating and intimidating at the same time could take on a sacred character, becoming itself a hierophany. Therefore, going beyond any kind of blasphemous and desecrating logic, through a path conditioned by the alternation of iconography and aesthetics of the grotesque, the two young artists would seem to start a process of sacralisation of something that no longer resides in the canonical standards of religious, but elsewhere.

By carefully observing the proposed works, it is possible to notice the recurring presence of the umbrella figure, which symbolises family congregation on beaches. This interpretation is supported by the fact that, in canvases, the umbrella pole supports the "crucified" figures, while, in sculptures, it is replaced by a totemic figure. The totem, in anthropology, is a supernatural entity around which a clan, a tribe, or a sort of family, is linked in terms of ancestry, creating a social system built on taboos and predefined rules. According to the French philosopher George Bataille, everything that is prohibited, as capable of imparting fear and at the same time devotion, takes on a character of sacredness. Therefore, the umbrella, in its protective function, becomes a fetish around building a community nucleus. Yet, Luisa Me's umbrellas, unable to generate shade, do not fulfil their predetermined defensive role from the sun, thus becoming futile. Furthermore, they do not have any family groups around them, but isolated, marginalised, alienated characters existing in their abnormal individuality. Therefore, the umbrella becomes a false idol embodying an ephemeral sacredness, a symbol of illusory fetishes raised by society in a game of superstructures.

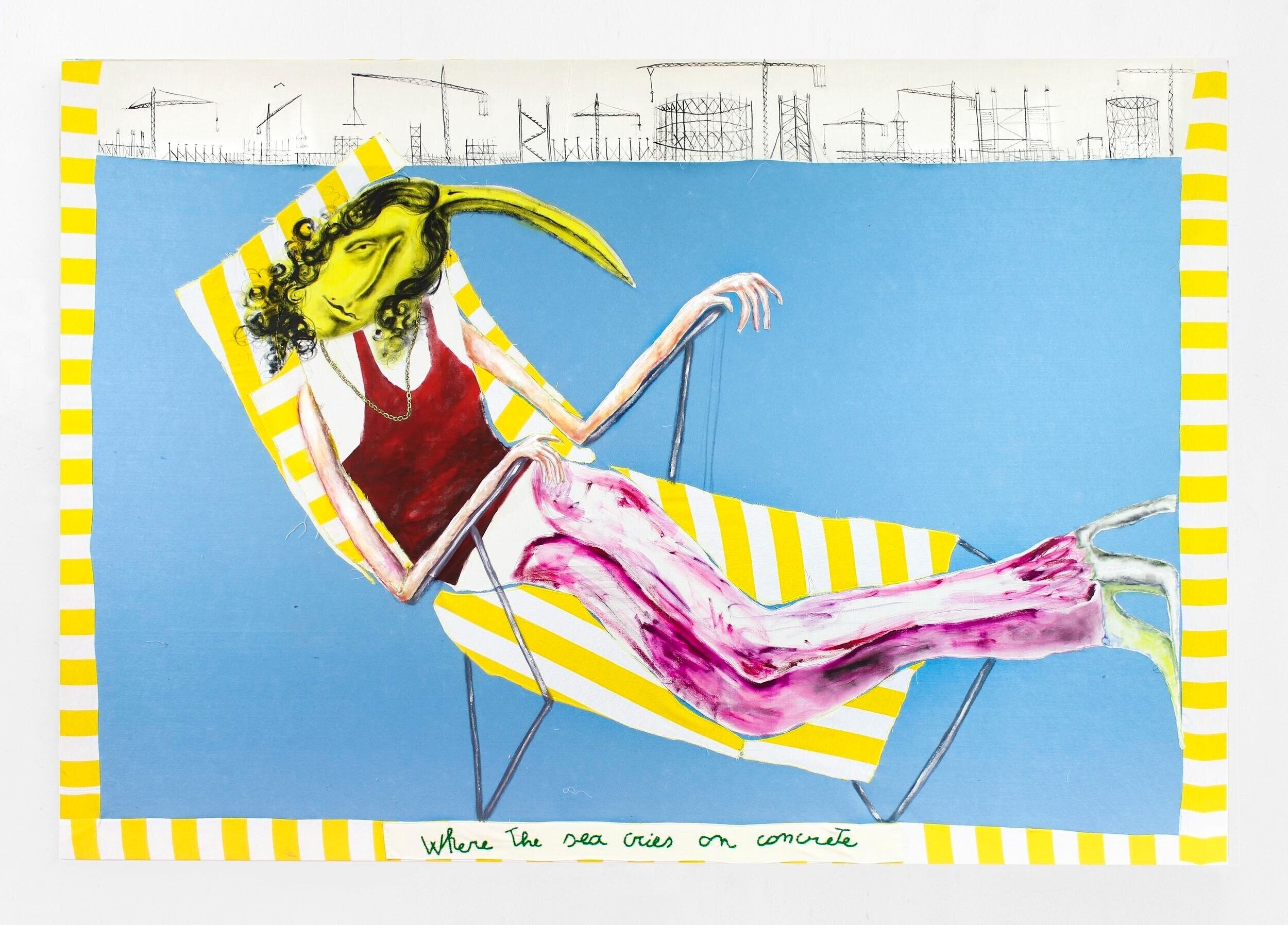

Where The Sea Cries on Concrete, 2021 and a scene from The Red Desert, 1964.

Going beyond iconography, the two young artists also provide subtle and perhaps haughty interpretations, translated into cultural references intended for the viewers. Through visual references, Luisa Me address the Italian cinema of the second half of the twentieth century. The desolated seaside landscape of works such as "Where The Sea Dies on Concrete" or "Tipasa", in which the horizon of the sea is decorated with cranes and scaffolding, recalls the industrial panorama of The Red Desert by Antonioni, the Venetian lagoon of Death in Venice by Visconti, and the dreamlike beaches of the Dolce Vita and 8½ by Fellini. The sense of incommunicability, a typical theme of 1960s Italian cinema, intended as a fatal legacy of our human condition and at the same time as neurosis caused by society’s rigid structures, is evident in the works of the two young artists. This condition is summed up in the thoughts of Albert Camus, to whom Luisa Me refers through their work titles, such as "Oran" and "Tipasa". The French philosopher reflects on the absurdity and irrationality of our ineluctable reality, defined as "sin without God". He describes"absurd" as the immediacy of human living in a world where God is dead and men are deprived of their alibis, rescued from their rational shelters, thrown unwittingly into a deep, misunderstood solitude. There is no other solution for men than to “commit suicide”, which metaphorically means accepting one’s own destiny, and therefore the impossibility of understanding the world in its fleetingness and absolute absurdity. However, the term suicide should not be understood in negative terms but as the awareness of one's limits within which one can find freedom.

An iconic character of Camus's thought is Meursault, the protagonist of "The Stranger" (1942), an indifferent, passive marginalised character who finds himself committing a senseless murder: blinded by the sun right on a beach, mistakenly shoots a man. By evading any kind of game and social construct, disinterested in what surrounds him, and for the sake of truth, he will admit his guilt, being sentenced to death. Hence, Meursault “commits suicide”, stressing that he cannot understand the universe and escaping from it. Camus himself defined Meursault as "a man in love with a sun that does not cast a shadow, a Christ we deserve". The sun, as in ancient mythologies, in Camus's work assumes a kind of sacredness. The sun radiates, gives life, but at the same time curses, taking on a character of necessity in an idol’s shape. The sun is heat, sadness, madness, cause, explanation; in other words, it is life and therefore absurd. Even in Luisa Me's works, the sun on the beach does not cast shadows, shining in its entirety. Hence, the grotesque and smiling figures who live in the universe represented by the two artists, like Meursault, do not seek the shadow, but capture and experience the sun, and therefore life itself in its absurdity, "suicide".

Tipasa, 2021.

Through a precise iconographic language that goes beyond the canonical Christian meanings and an artistic and technical approach that recalls the art of the past, the two artists create an interpretative path of their grotesque universe, in which the socially accepted concept of the sacred is put into doubt. Recalling the philosophical thought of the mid-twentieth century, one finds himself in an almost existentialist limbo in which angular shapes, unreal colours, contrasts of texture, paradoxical subjects are vehicles destined to search for a totem to adore, around which to create a social structure where the light of the sun that does not cast shadows. Therefore, Luisa Me’s art with its dreamlike and grotesque features is nothing more than the acceptance of the paradoxical condition of a world, today's one, impossible to understand, distressing, neurotic, but at the same time familiar and fascinating. To put it in Camusian words, theirs is a "suicide", understood as the awareness of the limits within which one can be free. Fascinated, intrigued, but at the same time perhaps frightened, Luisa Me, therefore, deny the false fetishes generated by pre-established social superstructures, sacralising instead life itself in its paradox. In other words, it is the totemism of the absurd.

Imagery courtesy of Luisa Me.

For more information on Luisa Me, check out its Instagram profile.

Federico Raffa

Feature Editor, MADE IN BED