From: Friends, To: Friends

Part 2: On The Journey

Ahlem Baccouche in conversation with Larry Ossei-Mensah on his journey into the art world, his stance on diversity, and much more.

Larry Ossei-Mensah. Image credit: Aaron Ramey.

Leveraging the power of art as an agent for social change and cultural transformation is the mission of ARTNOIR’s co-founder, art critic and international curator Larry Ossei-Mensah, whose latest initiative invites people to become agents of change in the art industry.

In the first part of this interview, Larry expanded on his partnership with Artsy for the ARTNOIR From: Friends To: Friends Benefit Auction, which aimed to raise funds for the newly launched ARTNOIR Jar of Love Fund, a microgrant initiative intended to provide relief for artists, curators, and cultural workers of colour.

In this second part, we discuss Larry’s journey into the art world, his views on diversity, his upcoming projects and advice on leading an authentic life.

Ahlem Baccouche: I’m always curious about the journey that led people to their current position, as life is never a linear path. What was your journey like?

Larry Ossei-Mensah: My starting point in terms of art and business was in high school, where I did internships at record labels like Epic and Columba Records from my junior year all the way through university. I wanted to be a record man, I wanted to be Diddy. That experience gave me my first exposure to the intersection of art and business. The art being music as a form of expression, but also music as a commodity: how it can be packaged, marketed, distributed and consumed.

That foundationally informs my thinking. When I think about an exhibition that I’m doing, I see it like an album release. How do I build content around a show that will be different than just a press release and an email blast? A good example of that would be the Phillips Auction conversation with Tremaine Emory, we used it not only as a space to talk about art, but also social justice and other issues currently impacting society.

I eventually realized that the music industry wasn’t for me, and worked a bit in marketing and advertising before going to Switzerland to complete a Masters at Les Roches. My mother worked in the hospitality industry for about thirty - thirty five years at the Waldorf Astoria, so there was always a romance of opening a hotel or something similar one day, as it’s an industry that I grew up in. That is something I still want to do in the long term.

Studying at Les Roches and being exposed to a truly international student body shifted my thinking about humanity and how we engage with each other. It taught me how to really value people, relationships, and perspectives that were different from mine. Just because you have two people from the same city, like New York, doesn’t mean they’ll get on. We can have very different experiences. My time at Les Roches also afforded me an opportunity to travel and explore Europe. As a graduate student, I didn’t have a lot of discretionary income, so I found things that were free and, a lot of the time, that would be museums.

The American education system makes you believe that there wasn’t a presence of Black people in Europe throughout history. However, by going to these museums in Europe, to a place like Florence’s Uffizi Galleries, and discovering paintings of Black people, even if they’re mixed, was mind blowing. That afro, is undeniable.

That exposure started an inquiry into who's telling the narrative of the Black diaspora experience? Who's controlling the story? So much is hidden from us or recontextualized. For example, one of Sicily’s patron saint is of African descent, Saint Benedict the Black, there are murals of this guy all over Palermo. It’s not a hidden secret, but it’s not openly discussed. I began this inquiry and started taking photographs as a way to document these experiences and began to exhibit these images when I moved back to the states. I exhibited a little, but quickly realized that being a photographer wasn’t my journey. After that epiphany, I started writing about art and that’s when I noticed that there weren’t enough platforms for artists of colour to have their work be seen, discussed and purchased.

This was over ten years ago, before it became in vogue. The ability to recognize that and be invested in it fully has allowed me to build a lot of relationships, which was the backstory behind the foundation of ARTNOIR. Knowing artists at the beginning of their career and having a decade-long relationship with them, whether I’ve shown their art or not, provided a spark plug for rich dialogue and collaboration with these artists. Moreover, building those relationships over time helped me shift and expand my thinking about contemporary art.

Larry Ossei-Mensah. Image credit: Aaron Ramey.

AB: From international curator, to entrepreneur, writer and cultural critic, you are very active. Where do you get your drive from? What gets you going?

LOM: When I started in the arts, it was also around the time when my dad died, so that was a wakeup call: that this physical life isn’t forever. If you’re not doing what you love, enjoy, and nourishes you then you’re wasting your time.

I’m motivated by the fact that I know that this is not an infinite experience physically. It’s a finite experience. So what do you do with this experience? How have you impacted another person’s life? As a person, how have I grown? How have I stretched myself in taking risks that I normally wouldn’t have taken? How can I be of service, but also how can I be an example?

When it comes to art, there aren’t many Black male curators. How do we change that? So how can I be a champion of other curators? What can I learn from others? I’m pretty clear of what my path is, my journey is, and I find inspiration from my colleagues who are doing what I don’t have the capacity to do. My undergraduate degree is in Business Management and my graduate degree is in Hospitality Management and Marketing. I've done some course work at NYU’s Art Business program and intensive. For the most part I’m self-taught with regards to my curatorial practice and I’ve enjoyed learning by doing.

In my practice, the motivation is the artist. There are so many artists that I met at the beginning of their career or got to know at different points in their journey, with whom I’ve been able to build some really incredible relationships. Hank Willis Thomas, Jordan Casteel, Kehinde Wiley….the conversations that I have with them and the things they tell me motivate me.

It’s also the collectors and aspiring collectors; people who are passionate about the art. That’s the thing about art, once you catch the bug, it's off to the races.

AB: What do you love the most about what you do?

LOM: The people that I get to know and build meaningful relationships with. Most of my learning is through doing and through conversations. There will always be exhibitions, but it's the relationships that you cultivate over time that make it all worthwhile. To have friendships with artists and become part of their family. To be recognized as an “uncle” to their children has so much depth to me. That’s a real relationship versus something that would be purely transactional.

It’s about supporting each other and making an impact. I think I've been able to make the impact that I wanted to make in music. I've been able to do that in the visual arts. When I think about the careers I've been able to help stimulate from the beginning and how these artists are now all working and thriving and in incredible collections; that for me is affirming, because I now know that they'll be able to leave whatever legacy they choose to leave.

AB: You are regarded as a cultural tastemaker. How do you manage this status and the responsibility that comes with it?

LOM: I'm very cautious not to buy into that. I know that I have the capacity to say that this artist is amazing and important and special; and that collectors and curators will be listening and paying attention. I'm conscious of that and I'm careful, and I never want to hold that over somebody's head. I think people recognize that I've put in the work, and I continue to put in the work.

You know, foundationally, my practice has been about supporting emerging artists in particular. So engaging with an artist at a point before anybody's added them to a list, or put them in a show, or said this artist is going to be a star; seeing a future for that artist that they might not even see for themselves and going on that journey with them. This is what I enjoy doing.

Larry Ossei-Mensah. Image credit: Aaron Ramey.

AB: Let’s talk about the issue of diversity and your experience as a Black curator. Have you ever encountered racism or discrimination in the course of your career, first-hand or otherwise?

LOM: I can't necessarily pinpoint one thing, but I can definitely say that there have been moments of microaggressions. I haven’t had a case where someone outwardly called me the “n” word. However, the art world has a tendency to have this kind of sleight of hand, where their questions, on the surface might seem innocuous, but are in fact privileged, ignorant, or downright stupid.

I’ve definitely had conversations like that, where when I’ve met people in the art world, nine times out of ten, they’ll assume things about me. They mostly think I'm an artist first (which there is nothing wrong with) or that I have to work for some institution as a curator for my work to be valid. I’ll be in a situation where someone will be referred to me, but will still ask me to tell them about myself, when they can do the research themselves. That tells me that they aren’t willing or interested to get a basic understanding of what I do. They just want to capitalize off my social currency.

When I was younger those situations might have created a doubt in myself and my abilities. It made me feel the need to do all these projects to validate my existence, which was totally misguided on my end. With time, I learnt how to deal with sideway comments, how to react to them, correct people and not be afraid to call it out. I think we're in a climate where people have gotten away with some really bad things; and I'm mindful of that when I'm working.

People who work with me have an idea of what they're getting. I'm not going to pretend to be super radical, because that's not me. I'm radical in my own way - but I think about giving the support and resources to the people who are more radical than me, so they can do their thing. I'm different in that I'm someone who was operating outside of the system. Now, I'm somewhat operating within the system, but I’m always conscious to not be co-opted by the system, where you become laissez-faire about things. I always make sure that I'm advocating for artists, getting the resources they need to work to the best of their ability when we do programming. It’s also about being willing to have those uncomfortable conversations with people who are in positions to make decisions. At the end of the day, this is all about trust.

There are certain people who trust me and will ask me things knowing they will not be judged. I will provide some insight and guidance, but that doesn’t mean I will do their homework for them. I will do my best to encourage them to do the research. I’ve had conversations with teachers who recognize that their curriculum is not diverse and ask me for a list of artists. You’re supposed to do the research. I can give you a couple of names off the top of my head, but I won’t do your homework! Most people aren’t going to ask the same question to someone if they needed ten white male artists. They will google it and figure it out.

AB: Are people open to having these uncomfortable conversations? What reception does it usually get?

LOM: There are always entities that keep things vanilla and don't want to have frank conversations about race, oppression, issues around identity, equity, inequity or social political topics. I'm sure I lost opportunities, because of it or because I’m Black, that I don’t know about. At the end of the day, as long as it's not something that's going to cause bodily harm to me or my family, I don't really obsess over it. But I recognize the challenges and I try to figure out, what can we do to fix it collaboratively? I think that's where ARTNOIR also becomes a great vehicle for this because it's an entity, it’s not me. It's an organization. It's a voice. It's a platform. And we have allies who utilize the platform to tell their story and to share their vision. The universe is now really forcing us to have these conversations and really unpack that. Why aren’t there more Black galleries? I know a big chunk of that is economic because it's expensive to run a gallery, but when at least, within this moment, a significant amount of attention and money is being made by artists of colour, that becomes a question, right?

We still need more curators of colour, across the board, not curators who are just focusing on African Art or Diaspora Art but with a focus on other disciplines as well. We need more writers. We need traditional folks and non-traditional folks. We need more artists who are working as curators as well because artists have the capacity to organize and curate. We need that spectrum of practice and understanding, because that allows for more people to be part of this; and to show more examples of how one can exist within this space.

I'm looking at the support that Black-led organizations and institutions get. What does that look like? I think the system tells you the story if you just look at the landscape. The system illustrates these challenges just based on who is where, who has what opportunities and who makes the decisions. I've also never been one to be beholden to the system, because the system has not been designed to consider me.

Joiri Minaya, Redecode: A Tropical Theme Is A Great Way to Create A Fresh, Peaceful, Relaxing Atmosphere, 2015. Image credits: Oolite Arts.

AB: In light of the Black Lives Matter protests that are happening in the United States and in other countries, what actions do you think the art world should take to become more diverse and inclusive and play its part in dismantling systemic racism?

LOM: I think it's a multi-layered issue that needs a multi-layered approach. Fundamentally, institutions need to admit that they are complicit in the amplification of this system that oppresses Black and Brown people. There's a book called Rogues’ Gallery that talks about the history of the Metropolitan Museum of New York. The MET was never designed to be inclusive of people of colour and working class people. They've worked towards that over time by force. If you're an institution, the structure upon which you’re built is inherently going to have biases and challenges, and recognizing that you have that is the first step.

Then, you must do the work of thinking about what you can do as an organization to be an agent of change. It's not enough to just hire Black and brown people. You have to put in infrastructures of support. What do Black employees at your organization need to feel fully supported? What is their recourse to file a complaint if they experienced prejudice? I think people should feel that they have tools to speak up and not be concerned that there will be retribution. And that's inherent in institutions. So how do we unpack that?

I'm looking at things like diversity training and anti-racism training. As an organization, what are the new standards that you're setting for everybody to be accountable, not just senior staff, not just lower level staff, but everybody being accountable? Not expecting your five staff members who form a diversity task force to solve this large problem, because everybody needs to be at the table.

We need more galleries of colour within the ecosystem, but then we also need to support the galleries of colour who've been doing the work. How can we make sure they have the resources to survive, thrive and continue to make the impact? Art schools must also have a more diverse curriculum.

The key thing to it all is action, not lip service. We don't need statements, we need accountability. There needs to be an understanding that this is a continuous work and that it won’t end tomorrow, next year, five years. This is something that you have to continually be committed to doing. What does your collaboration look like? If you're a well-resourced entity, are you collaborating with entities that are doing the work that might not have the resources that you have? From a dealer standpoint, if you're a gallery showing the work of artists of colour, you should be selling to collectors of colour. I can't tell you the amount of times that collectors who wanted to buy an artwork by an artist couldn't even get into a conversation because they didn't fit the pedigree or didn't have the right introduction. This is part of the infrastructure that needs to be dismantled and that needs to be addressed in a meaningful way. It's also incumbent to the artists to do that as well. The artists need to demand that these collectors have access to the work first.

It's a spectrum of things and it's very complicated, but I'm not going to say it's impossible. Taking a step forward, removing this facade, making things more transparent, making things more equitable, making the actionable change across the board from the commercial to the non-commercial. It's a multi-layered approach. There's no silver bullet.

The key is action, doing the work and not just placing the burden on the POCs that work at your institution. And, treating people with respect, because the art world has this tendency to be condescending. And I'm not with it.

Temples of My Familiars R Squared Triangular Fractals, The Yin and Yang Over Color Theory by Amber Robles-Gordon. Image credit: Amber Robles-Gordon website.

AB: What projects are you currently working on?

LOM: I will be co-curating the 7th Athens Biennale with OMSK Social Club, which has been rescheduled for Spring 2021.

I'm doing a show in Rome in November as part of a series of exhibitions called Parallels and Peripheries. The show in Miami included only women artists. In Detroit, we looked at the intersection of Art, Technology, and Nature. In Maryland, the theme was about migration and immigration, and it included first generation immigrant artists. The show in Rome is called Fragments and Fractals and is held at Galleria Anna Marra (a 3D viewing is available).

We’ll be thinking about fractals as a mathematical concept, the potential to repeat infinitely, and exploring the idea of fragmentation when thinking about layered identities. As an example, I'm Black; I'm African American; I'm also Ghanaian; I'm a New Yorker; I come from a working class background; I’m a male. We try to look at the different layers that compose a person, not just from an identity standpoint, but also from a practice standpoint.

The show includes six Black artists: Kim Dacres, Kenturah Davis, Basil Kincaid, Nate Lewis, David Shrobe and Kennedy Yanko. They all work with different mediums such as sculpture, photography, drawing and painting. It will be the first show in Italy for some of them. Just think about the social climate in Italy, particularly for Black folks. How do we use the exhibition as a platform to key in on those things? I also highlight that the fact that we're Black does not mean that we're a monolith. We're very vast and very diverse in our experiences, our thinking and our creative approach.

Next, I have a show at the American University in 2021 with Amber Robles Gordon, an Afro Puerto Rican artist based in DC. It will be a solo show of just abstract work, which is exciting for me, because I don't think I've done a solo presentation of just abstraction. So I seize this opportunity to educate myself on movements like the Washington Color School and look at artists like Alma Thomas more closely.

It's also interesting to mine this layer of the diasporas: so thinking about the African diaspora experience from a Latin perspective, but then also from an American perspective, because the artist grew up in the United States as well.

Lastly, I'm toying around with the idea of writing a pocket book on my experience in the art world. I gave a lecture with Oolite Art at Anderson Ranch called “Lead with the Hustle.” I describe my journey, but also talk about things that I've recognized that I believe not only artists, but all people should be aware of.

From storytelling, to relationship management, professionalism, likeability and how to operate on a professional level consistently. It’s about how to work within the art world from a business standpoint and think about storytelling through your work. What is your story? If I was doing an article on you, what would that story look like? Why do you do what you do?

AB: Are there any artists, curators, businesses, colleagues, or organizations whose work you admire and would like to highlight?

LOM: In terms of curators, Okwui Enwezor of course. I’m following many curators who are doing a lot of incredible work internally and externally. Among them are Meg Olni from ICA Philadelphia, Erin Christoval from the Hammer Museum and Osei Bonsu at Tate Modern.

I like what SAVVY Contemporary is doing in Berlin. In terms of fashion, I love what Pyer Moss is doing. They just released a sneaker of which the proceeds will go towards The Innocence Projects.

AB: Any favourite advice, resources or tips you’d like to share?

LOM: It goes back to the pillars: really understand why it is you've chosen to work within the arts. I think that understanding the why, for me, informs everything else. It’s going to inform where you’ll choose to work; it's going to inform your values. I recommend this book called Start with Why.

Cultivate meaningful relationships. The art world in particular, is about human connection. You'll know a lot of people, but how many of those people are meaningful relationships where you can pick up the phone and call if you have a question, or an issue. How many of those people would you invite over to your home for dinner?

Branch out. Build a support system. This is going to be a journey and you need people from different spectrums. When we think about mentorship, it's always kind of thinking of an old wise person, and that's antiquated. We need to change the way we think about mentorship, as it doesn’t necessarily have to be with an older, wiser person. I think peer mentorship is just as valuable.

In terms of books, Never Eat Alone is a great book about relationship building. Some people will call it networking, I prefer “relationships” as “networking” feels more transactional. Who Moved My Cheese is a good one to adapt to change. Collecting Contemporary by Adam Lindemann, particularly for artists who want to get a snapshot of the industry. The Hard Things About Hard Things is a business book coming from an honest perspective. Usually, when you hear about a business, you only hear about the success. You don't hear about the pitfalls, running out of money, being broke and the resilience that it takes. Being an artist is not easy, so you need to make sure to have the tools and the support to navigate the ebbs and flows of this journey.

And my final tip: Stay true to yourself.

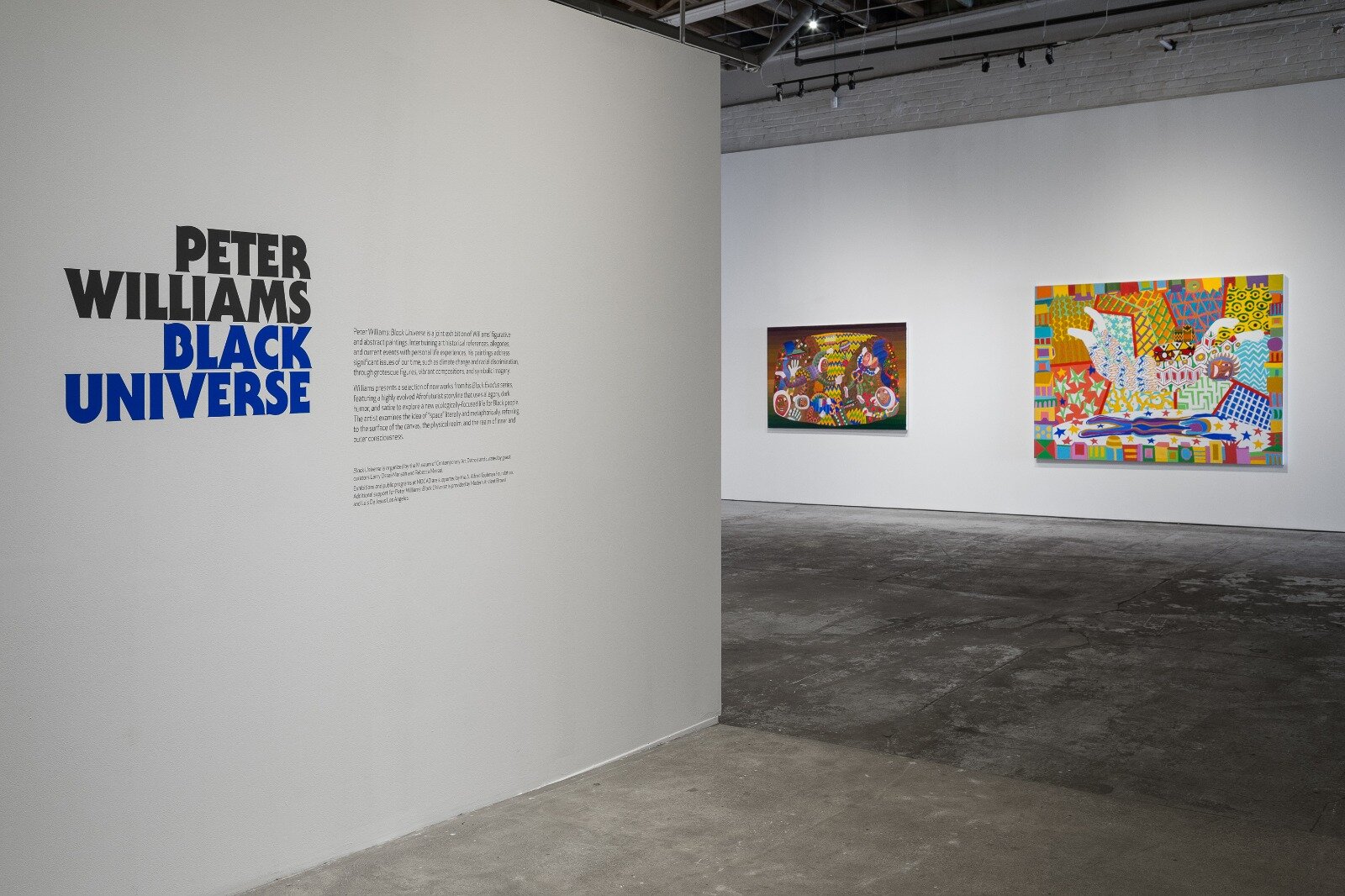

Peter Williams Exhibition: Black Universe. Image credit: Tim Johnson and MOCAD.

Peter Williams Exhibition: Black Universe co-curated with Rebecca Mazzei. Image credit: Tim Johnson and MOCAD.

Lizania Cruz, We The News, 2018. Image courtesy of Oolite Arts.